Women’s History Month – Jocelyn Robson

6 FACTS ABOUT ELIZABETH HEYRICK

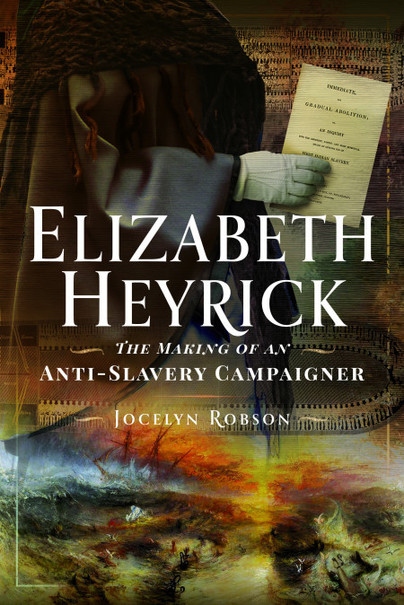

Elizabeth Heyrick (1769-1831) grew up in Leicester. She fought fiercely for the rights of the oppressed. She opposed animal cruelty and campaigned for better working conditions for framework knitters. She was bitterly critical of legislation prohibiting vagrancy but is best remembered now as one of slavery’s most outspoken critics. She has been hidden in the shadows of the abolitionist movement for two centuries and this is the first full-length account of her life and legacy.

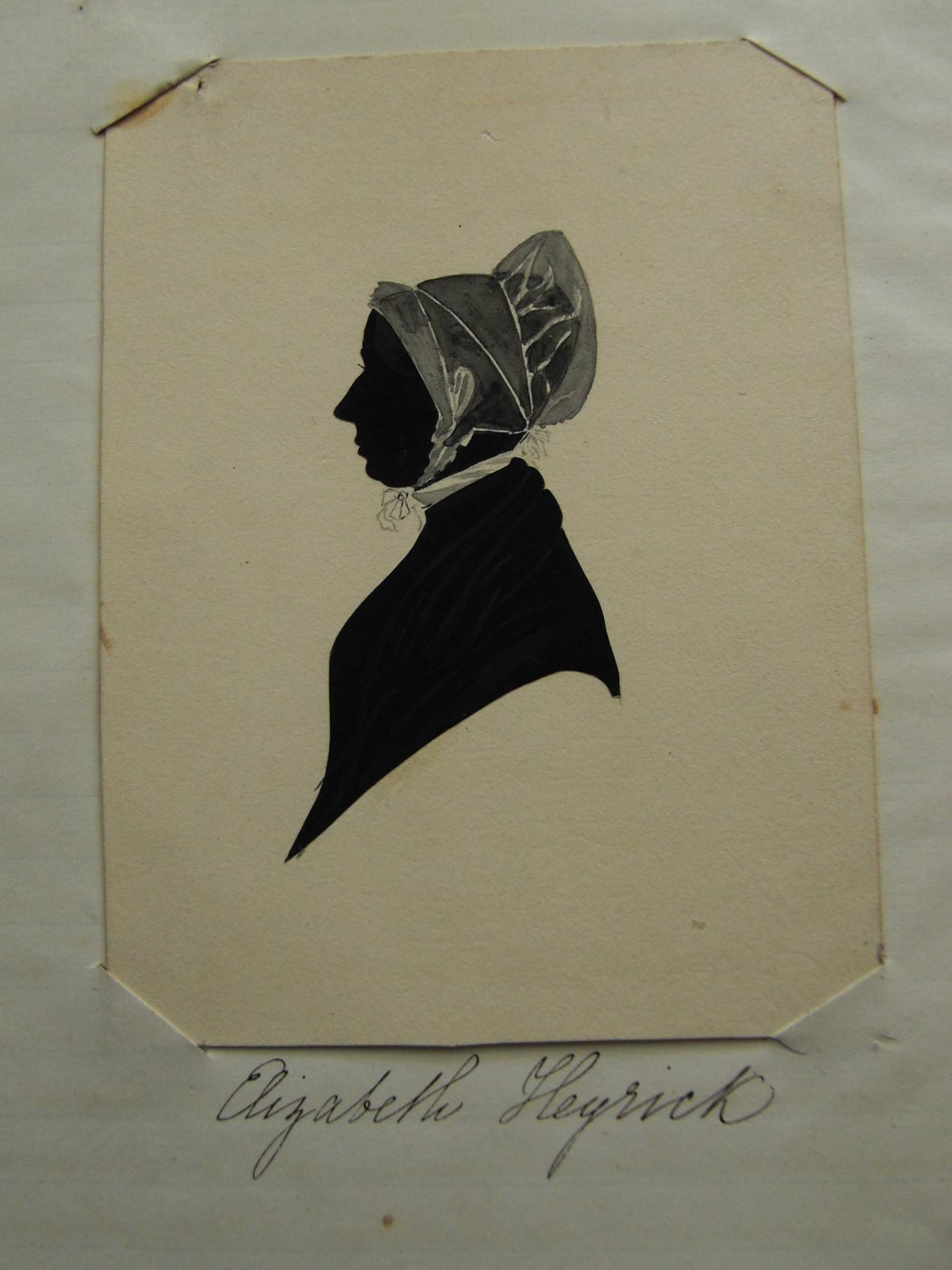

Like most Quakers at the time, Elizabeth is likely to have preferred silhouettes to painted portraits. This one in black card, carefully preserved by her descendants, was cut in about 1824.

What else is there to know about Elizabeth Heyrick?

- Elizabeth made a disastrous marriage when she was still a teenager. She was widowed a few years later and never recovered from this loss.

Her husband John Heyrick believed he was descended from the 17th century lyric poet Robert Herrick who is best remembered now for his line ‘Gather ye rosebuds while ye may’.

- Elizabeth did not suffer fools gladly and in her published anti-slavery pamphlets, she challenged the views of leading members of the political establishment, like William Wilberforce.

She was especially critical of the male members of the Anti-slavery Society and accused them of ‘puerile cant’ as they argued for a gradual rather than an immediate end to slavery.

- During summer vacations, she sometimes stayed in a shepherd’s cottage where she restricted herself to a meagre diet of potatoes so that she could experience first-hand the life of an impoverished Irish labourer.

On another occasion, she gave a guinea to an Irish beggar and told him he was to repay her when he was able to. She then found him a job and he returned a year later to repay his debt.

One of the early framework knitters’ workshops in The Dale in Bonsall was first built in 1737. This photograph was taken in 2017, and the building has since been renovated.

- She became a Quaker in later life. She wrote and published over twenty anonymous pamphlets.

During a visit to Derbyshire one summer, she challenged those taking part in a local bull-baiting contest in the village of Bonsall. She demanded that they should spare the animal. Women seldom took direct action in public but when the villagers refused to stop, she purchased the bull from its owner and led it away to safety. Then in her first two pamphlets, she challenged the traditional practice of bull-baiting.

- She led women in successfully demanding the removal of the word ‘gradual’ from the title of the main anti-slavery society.

She could not support the gradual amelioration of slavery and she and her colleagues in the Birmingham’s Ladies Anti-slavery Society threatened to withhold their subscriptions from the main society if its name was not amended.

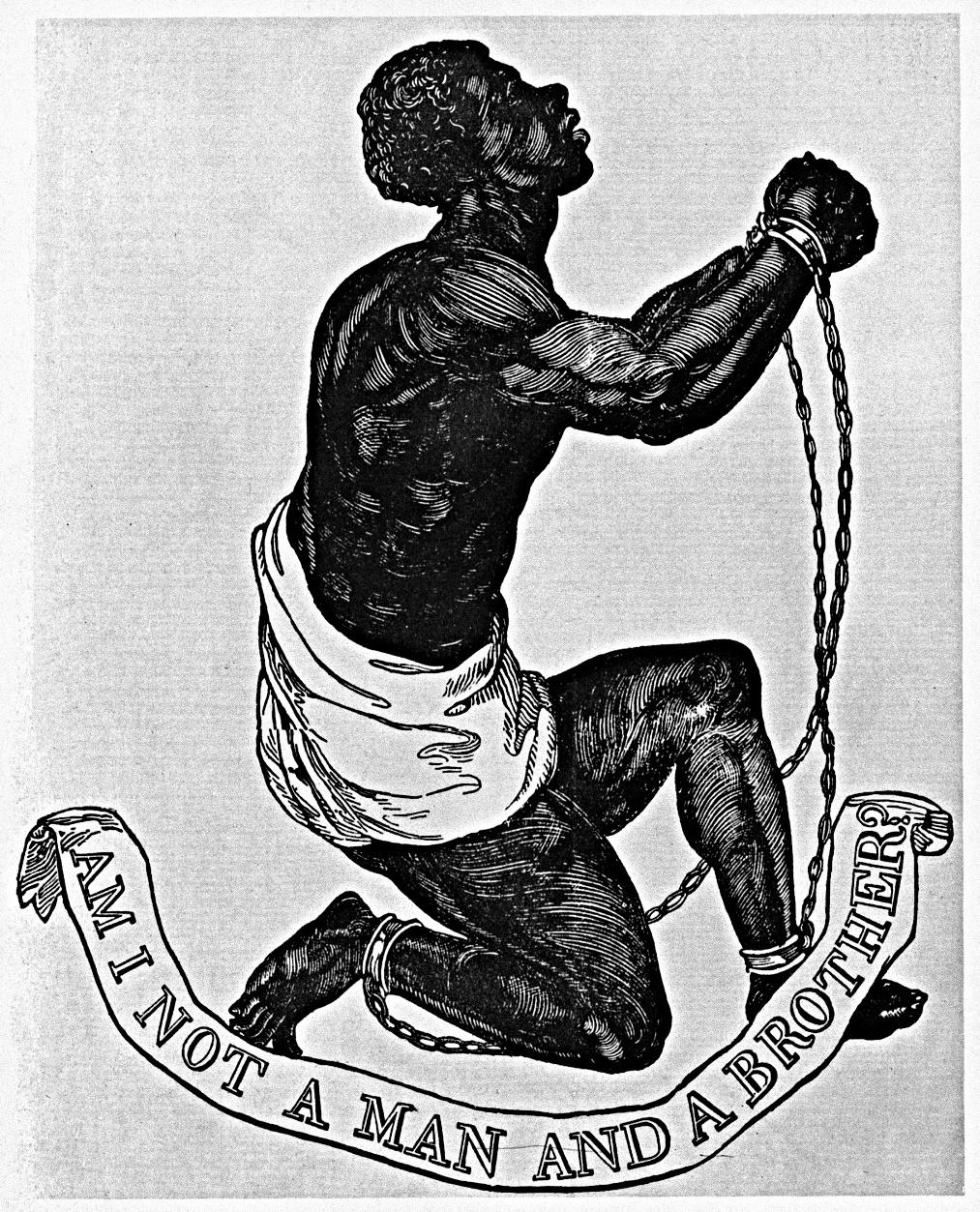

This iconic image, made in about 1787, became an international symbol for the abolitionist movement.

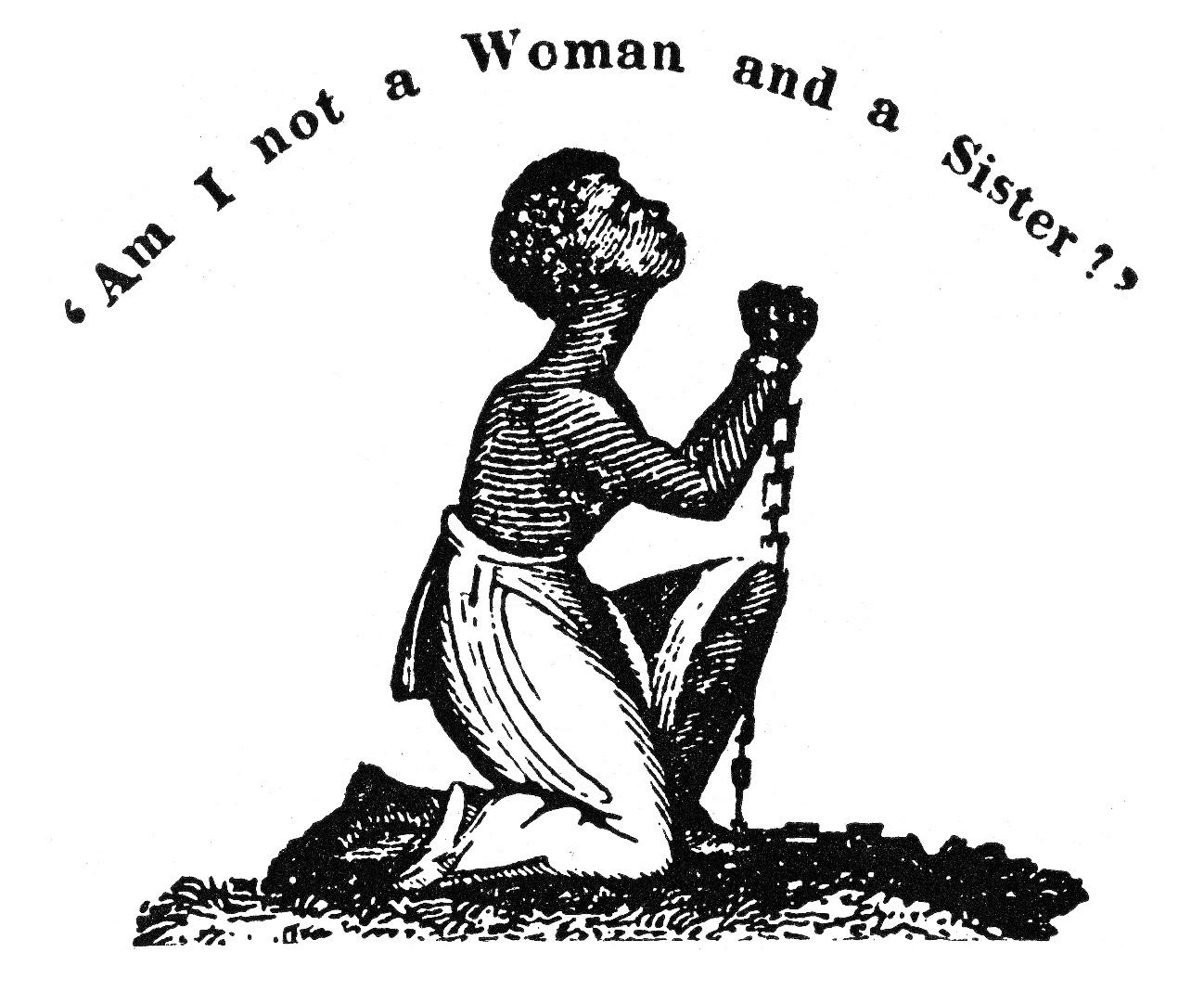

In the 1830s, in a conscious echo of the earlier image, this one appeared emphasising the impact of slavery on women.

- Many of her contemporaries found her too outspoken but she was cherished by her female friends. Her passing was mourned by abolitionists on both sides of the Atlantic.

One who felt her death particularly and sought to have her contribution to the anti-slavery cause more widely acknowledged was William Lloyd Garrison, an American publisher and abolitionist. It was not Clarkson or Wilberforce who hurried slavery to its overthrow in the United Kingdom, he claimed, but a woman from the Society of Friends whose pamphlet urging immediate emancipation had electrified the country.

A portion of the Roman Jewry Wall in front of St Nicholas Church still stands. In the 18th century, the wall provided rich pickings for Elizabeth’s father, John Coltman, in his search for old coins.

Jocelyn Robson

Order your copy of Elizabeth Heyrick here.