The Great Miss Lydia Becker

Author guest post from Joanna M Williams.

Lydia Becker, born in Manchester, was a leader of the women’s movement throughout Britain during the later 19th century. The injustices and abuses against which she campaigned bear many similarities to those faced by women even today. But she and her contemporaries deserve credit; they began an unstoppable momentum towards equality for women which is still rolling on today.

Like many modern activists, Becker demonstrated in speeches and writings her concern about all forms of abuse of women. She referred to the ‘torture’ and murder of women by their husbands, and even had to condemn a wife-sale in Lancashire. Much of her information came from the campaigner, Francis Power Cobbe.

In the 1860s on marriage a woman’s autonomy, never very significant, was removed. Any property owned, inherited or earned by a wife became the possession of her husband. Men could, and sometimes did, legally seize all their wives’ property and money and leave them and their children destitute. Although never a wife herself, Lydia believed strongly in married women’s rights, suggesting that they contributed to a household just as much as a husband through their domestic duties. She went so far as advocating that they should be paid. With Elizabeth Wolstenholme, Lydia was a founder member of the campaign for married women’s property rights as its treasurer for the first six years. Even after that she continued to support it through articles in her Women’s Suffrage Journal, and by the 1880s, a sound start had been made in the reform of this economic abuse of women.

Lydia believed that another reason why women were so vulnerable to economic abuse was that they lacked the education to become self-supporting and gain well-paid work. She herself had been educated at home and was largely self-taught, and she expressed frustration at being excluded from the university education open to her brothers. When she became the only woman on the Manchester School Board, she made it her business to focus on the education of girls, insisting that it should be academic, rather than preparing for them for life as a housewife or a servant. She held the board to account for spending less on girls than boys, and for failing to offer them lessons in subjects like geography and mathematics.

Her chief personal long-term aim was to become accepted as a serious scientist specialising in botany, and she corresponded with luminaries like Darwin and Wallace. She broadened this into a mission to open and encourage access to science education for girls, a project which is still ongoing even now. At first the all-male scientific community refused to give women access to their societies, but Lydia lived to be admitted to the Manchester Geographical Society, and the London Anthropological Institute. And some girls in Manchester were successfully studying chemistry by the 1880s.

When women did aspire to, or even gain, better-paid jobs, it was often the case that men felt threatened and therefore attempted to close those avenues to them. A notable example is the women in mining communities who fiercely resisted legislation to ban them from their relatively well-paid work at the pit-head. It was put forward by trade-unionist Thomas Burt, ostensibly for their protection, but in reality to end competition from female workers. Lydia joined with other feminists, notably Josephine Butler, to challenge this attempt by meeting with ministers at Westminster.

She also focused on improving the opportunities, pay and conditions for traditional female occupations which were generally the lowest paid, such as millinery and dressmaking. Unlike most contemporary feminists, who tended to be of the middle class, she was interested in the treatment of domestic servants, and advocated that the value of such work should be reflected in higher pay. Even now we have not properly addressed the issue of low pay and poor conditions for jobs predominantly carried out by women.

But for Lydia Becker, women’s suffrage was the crucial campaign; as she saw it, the lack of political power was the root cause of all the disadvantages under which women laboured. Not only were there no women MPs, there were no women voters. Throwing herself into the struggle with total dedication, for 20 years Becker was the acknowledged leader of the movement. She helped lay the foundations on which later campaigners were to build, by changing attitudes both in parliament and in society at large. It was widely felt by the time of her death that it was a question of ‘when’ rather than ‘if’ women got the vote on the same terms as men. However, despite success in 1928, the male/female imbalance in parliament still remains.

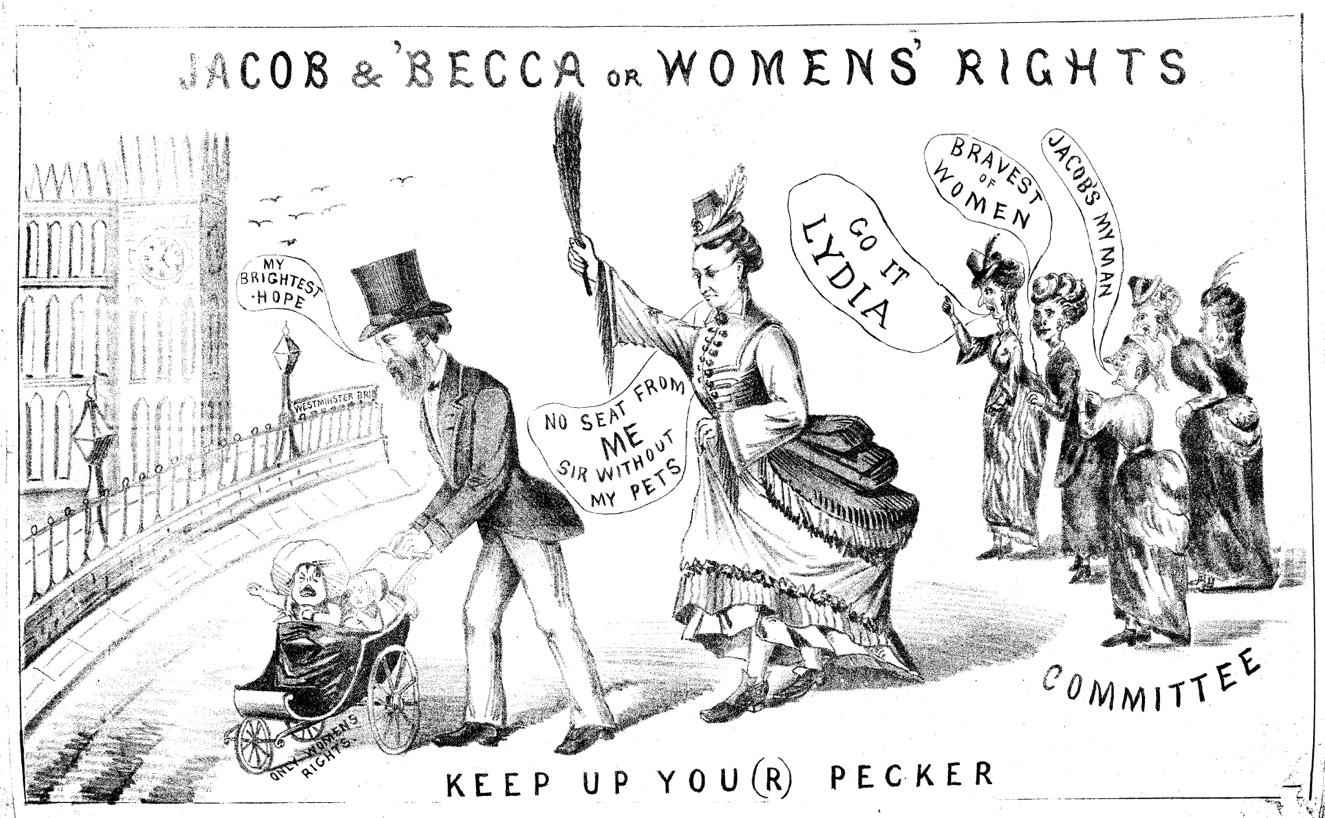

The path of a mover and shaker has never been smooth, and some of the attacks in social media which feminist campaigners endure today also had their parallels in the Victorian era. Cartoons appeared which showed the women’s rights campaigners as aggressive, strident, ugly, ill-dressed and unfeminine. Whilst milder than some of the attacks on modern campaigners, in their day these images were every bit as threatening to women unused to public exposure.

Lydia Becker beats the effeminate (because pushing a pram) Jacob Bright, candidate for Manchester, into submission to her ‘pets’. She is showing an unladylike ankle with big feet, and wearing her signature steel-rimmed spectacles. The elderly, ugly and ill-dressed committee cheer her on.

Lydia Becker and her fellows set the scene for subsequent women’s campaigns, and handed on the torch to later activists, who have eclipsed them. Their work to give women autonomy, equality and freedom goes on even today.

The Great Miss Lydia Becker is available to order here.