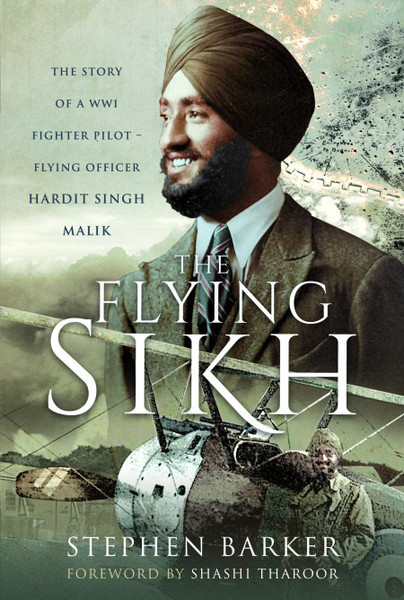

The Flying Sikh

Guest post from author Stephen Barker.

On a warm afternoon in June 2018, whilst working at a ‘Digital Collection Day’ at the King’s High School in Warwick, I decided to start writing this book. The event was one of those run by the University of Oxford, part of the ‘Lest We Forget’ programme associated with the First World War Centenary, aimed to capture the memories and stories of participants before they were lost to history. A colleague drew my attention to a photographic album brought in by a member of the public, Mark Haselden, the grandson of Eric Haselden, who flew with 141 Squadron during 1918. The album had been compiled by Eric and is beautifully preserved.

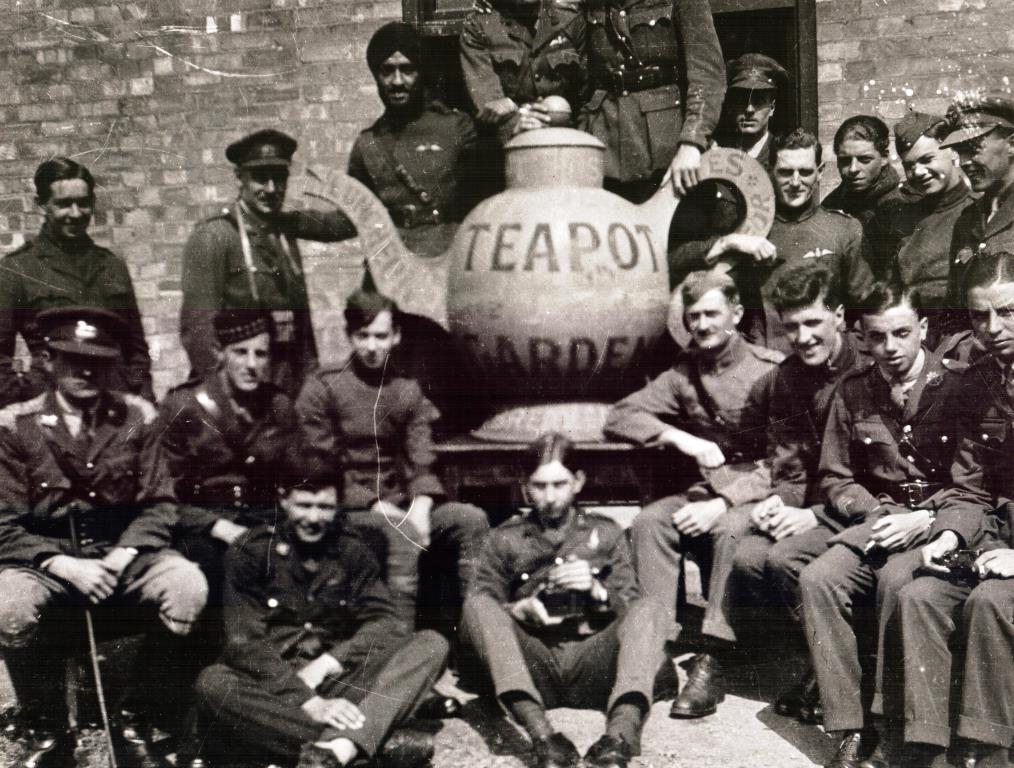

One of the photographs caught my eye immediately, at its heart was an oversize sign in the shape of a teapot, an advertising hoarding as it turned out, larger than any of the nineteen men surrounding it, some of whom were wearing Royal Flying Corps (RFC) uniforms. All were looking into the camera, some smiling, others rather more sternly. The image also attracted my attention for another reason: in the background was the figure of a man I recognised instantly. Having attempted to identify individual soldiers believed to be concealed in grainy Great War snapshots for over twenty-five years, I had become rather sceptical about such recognitions, but on this occasion, there was no doubt. The familiar face of Hardit Singh Malik looked calmly towards the camera, his right hand resting on a nearby shoulder and the other linked through that of the airman to his left. I later came to know the full story of the photograph’s significance, but there and then in Warwick that day, I knew it had been taken at Biggin Hill, one of those names synonymous with the Royal Air Force.

Lieutenant Hardit Singh Malik would be the only Sikh on active service with the RAF when the Armistice came on 11 November 1918. He was one of a handful of recruits from South Asia who had managed to enlist on behalf of the Empire whilst living in Britain. His education and career in the RFC and subsequently the RAF, in the ten years after 1909, would underpin what was to be, by any standards, a successful and fulfilling life. With significant achievements to his name in the spheres of diplomacy and sport and fortified by family and by friends made around the world, his was a name which came to earn the utmost respect.

I believe that Hardit Singh’s story is rather more important than perhaps he, a modest man, realised. As a western educated Indian flying officer, his experiences bore witness not only to the challenges of being an Indian serving amongst Europeans, but also offered a unique perspective of the RAF in its embryonic stages and in which so few Indians fought during the war. None of the other South Asian airmen or indeed soldiers who managed to enlist in the armed forces whilst living in Britain have bequeathed to us any significant autobiography. For as historian Santanu Das reminds us, there is no homogeneous Indian war experience and one of the joys of researching Hardit’s war was understanding just how unique his perspective was.

Stephen Barker

Buckingham, May 2022

The Flying Sikh is available to order here.