Exclusive Interview: Simon Pearson

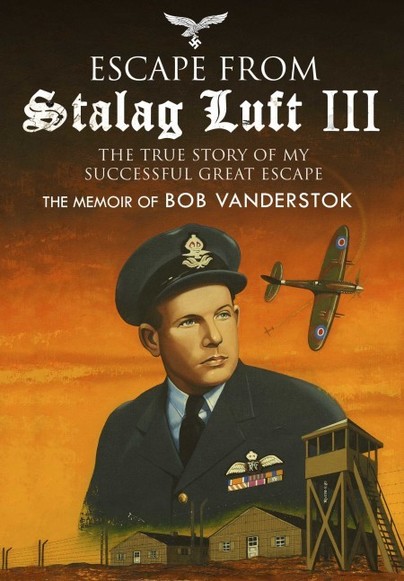

Simon Pearson has worked on The Times since 1986. He is the author of the bestselling The Great Escaper: The Life and Death of Roger Bushell (Hodder, 2013), described by the Sunday Times as “enthralling, an astounding story of honour and resilience”. Simon has written the Foreword for the newly published memoir of Bram ‘Bob’ Vanderstok, Escape from Stalag Luft III – The True Story of My Successful Great Escape.

1. Did the breakout from Stalag Luft III in March 1944 achieve anything significant? Or was it simply a distraction from the boredom of incarceration?

These are always the key questions. The answer is multi-layered, but a vigorous and emphatic “Yes” to the first part of the question.

Contrary to popular belief – and much cinematic mythology – the officers incarcerated in Stalag Luft III, or elsewhere, did not have a clearly laid down “duty to escape”, although MI9, the intelligence agency that worked with the prisoners and supported them, promoted this viewpoint. According to Norman Crockatt, head of MI9, a “fighting man remained a fighting man”, whether he was in enemy hands or not, and that a soldier’s duty to “continue” fighting overrode everything else.

Roger Bushell, who worked closely with MI9, was perhaps the greatest proponent of this philosophy. His project, now popularly known as the “Great Escape”, was complex and cannot be judged solely by the number of men who got out of the camp or back to England.

Even on this basis it was a success. Seventy-six men got away from the camp, and three made it back to Britain, making it one of the most successful escapes of the war.

Its impact was unsurpassed. At a time when the Germans were under strain on all fronts, the escape just added to the pressure, right at the heart of the home front. The escape was discussed by the German high command within hours of its discovery. Adolf Hitler, according to his leading generals, was “enraged”, and demanded the execution of the recaptured officers. A little later, the escape and its aftermath were being dealt with by Winston Churchill. If events are judged by their impact, The Great Escape was significant.

In practical terms, the escape rattled the Nazi security forces, which issued a national alert. There is much debate about the extent to which it tied up German resources in the hunt for the escaped officers; the numbers of people said to have been be involved range from thousands to millions, including members of the SS and Gestapo, Hitler Youth and home guard. Some feared that the Allied officers, nearly all highly trained airmen regarded as among the elite, would join resistance groups in Occupied Europe. Many Germans regarded the breakout as seriously embarrassing, and it led to increased tension between the Luftwaffe, which ran the camp, and the SS, which wanted to bring Stalag Luft III under its jurisdiction.

There were other achievements related to the escape, perhaps greater than the escape itself.

The X organisation demonstrated the power of the Prisoner of War and succeeded in subverting the running of the camp – one German officer is on record as having complained that Bushell was virtually in charge – and compromising many German staff. This was a significant achievement.

But perhaps their greatest achievement was the establishment of a major intelligence operation, garnering information useful for the escape, but also collecting extensive military data, including information about the new “wonder weapons”, the V1 and V2, which was relayed back to London as part of a highly sophisticated coding operation, which was never broken by the Germans. Indeed, Stalag Luft III became an outpost of British intelligence, operating in breach of the Geneva Convention.

The activity associated with the escape might well have been a wonderful distraction, but it was also a means by which the men of North Compound continued to wage war on Nazi tyranny.

2. German Prisoners of War made escape attempts from camps in Britain: how similar were their attempts and could any be regarded as successful?

German

prisoners of war held in Britain – and those shipped to the far

reaches of the Empire – showed just as much courage and ingenuity as

their British counterparts in Germany. There are dozens of stories.

Escape activity was widespread. On one occasion in late 1941, two

German airmen escaped from a camp at Shap in Cumbria and, pretending

to be Dutch airmen, stole a training aircraft from RAF Kingstown near

Carlisle. The aircraft didn’t have the range to get them home, and

they eventually landed near Great Yarmouth, but I’m sure James

Garner and Donald Pleasence would have been impressed. On another

occasion, much later in the war, 84 German prisoners escaped through

a tunnel at Island Farm, known as Camp 198, near Bridgend in south

Wales. They were all recaptured but some got as far as Birmingham and

Southampton. The tunnel was shored with wood from canteen furniture

and their beds; the tunnel was lit with electric bulbs and the

escapers carried homemade compasses and identity cards forged in the

camp. Sound familiar?

Only one German prisoner, a fighter ace called Franz von Werra, made a “home run” after escaping from a British Prisoner of War camp in Canada. His story was the subject of a book, The One That Got Away, and a 1957 film with Hardy Kruger. Another good escape story is As Far As My Feet Will Carry Me by JM Bauer, which is the story of a German soldier’s epic trek across Siberia after escaping from Soviet captivity.

3. Or does the breakout bear any similarity to the Japanese Prisoners of War escape in Australia?

The

Great Escape at Stalag Luft III bears no resemblance to the great

Japanese escape at Cowra in New South Wales in 1944. The motivation

behind the escape and the means used by the Japanese were entirely

different; it was also of a different scale. Under the Japanese

military code, it was regarded as shameful to be taken prisoner.

According the novelist Thomas Kenealley, who has written about the

escape, many Japanese prisoners felt they had no choice but to take

part in what amounted to a “suicidal” escape attempt. “The only

self-exoneration was to charge the wire,” Kenealley wrote. About

1,100 Japanese prisoners armed with baseball bats, clubs and knives

did indeed charge the wire at the sound of a bugle one night in

August 1944; 359 succeeded in breaking out; 231 were killed or

committed suicide. Several Australian soldiers were killed too. All

the prisoners were recaptured.

4.

Can you describe Bushell in five words?

Heroic

but flawed organising genius.

5.

And the same again for von Lindeiner.

Honourable,

courageous yet deeply naive

6.

50 men were executed after the Stalag Luft III escape: was the

disruption caused enough to justify the loss of life? Did the

breakout really boost morale?

The

success or failure of the escape cannot be judged against the

disruption caused, or the effect on morale. It was an act of war, and

must be seen as part of the Allied effort to defeat the Nazis. As

Edmund Burke said: “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil

is that good men do nothing.”

7. Was

the escape – in the words of Hermann Glemnitz – a ‘silly idea’?

Would a greater number of operations on a smaller scale have been

more likely to succeed?

A

number of very smart smaller operations might have succeeded in

getting more prisoners back to Britain, but they would not have had

the impact of the Great Escape. Glemnitz was wrong. Bushell had much

wider aims.

8. Stalag Luft III is known to millions of people throughout the world because of the film, The Great Escape. The film does not claim to be a documentary but how accurate is it and does it do more damage than good to the legacy of the Prisoners of War?

The Hollywood film is true to the spirit of the Great Escape, and gives a clear picture of the prisoners’ motives and ingenuity, which has enhanced the legacy of the Prisoners of War, but it is inaccurate in several key respects that probably underplays their courage and endeavour. When the men broke out of North Compound, they faced the most difficult wintry conditions, with deep snow and freezing temperatures. The prisoners knew that very few stood any chance of being at large for long. In the film it is spring, and the going is much easier. There is no reference to the intelligence operation either, nor is there in Paul Brickhill’s book, published in 1950, but then the papers dealing with such material were still secret when the film was made in 1963.

The

one prisoner who is perhaps not served as well by the film as he

might have been is Roger Bushell, Big X himself. In one of the war

stories most cherished by British audiences, the man at the centre of

events was largely forgotten in the aftermath of the film. Bushell

did not make the transition from paperback to celluloid in the same

manner as Guy Gibson (The Dambusters) or Douglas Bader (Reach for the

Sky), who were the subjects of two other hugely successful books by

Brickhill. With an eye perhaps on the fictional Virgil Hilts, played

by Steve McQueen, Hollywood chose composite characters for The Great

Escape rather than real people and the remarkable Roger Bushell – a

Cambridge-educated barrister, international skier. Spitfire pilot and

great romantic – became rather two-dimensional. And he did not even

retain his own name – instead he was Roger Bartlett.

9. If you could ask Bushell a question what would it be?

You spent seven months in Prague in 1941-42 living with members of the Czech resistance. Did you play any part in preparing the successful attempt to kill the SS chief Reinhard Heydrich in the Czech capital in 1942? I would ask this question because Bushell’s lover in Prague and her family were believed to have links with those involved in the assassination and were executed after Heydrich’s death. How closely Bushell was involved is not at all clear, but it seems unlikely that he would not have been aware of the plans if not implicated.

10. Were the Prisoners of War who organised the escape exceptional men? Or ordinary men in exceptional circumstances?

I am not familiar with the lives of all the men on the X committee, but there were a number of extraordinary characters, who were both motivated, perhaps by Bushell’s leadership, and accomplished. War tends to create exceptional circumstances, which bring out both the best and the worst in human beings. What is clear is that they all followed the doctrine laid down by Norman Crockatt at MI9 and remained “fighting men” in captivity.

Escape from Stalag Luft III is available to order now.