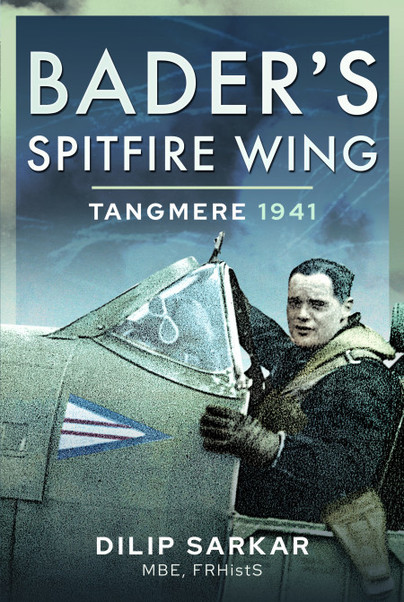

Bader’s Spitfire Wing: Tangmere 1941

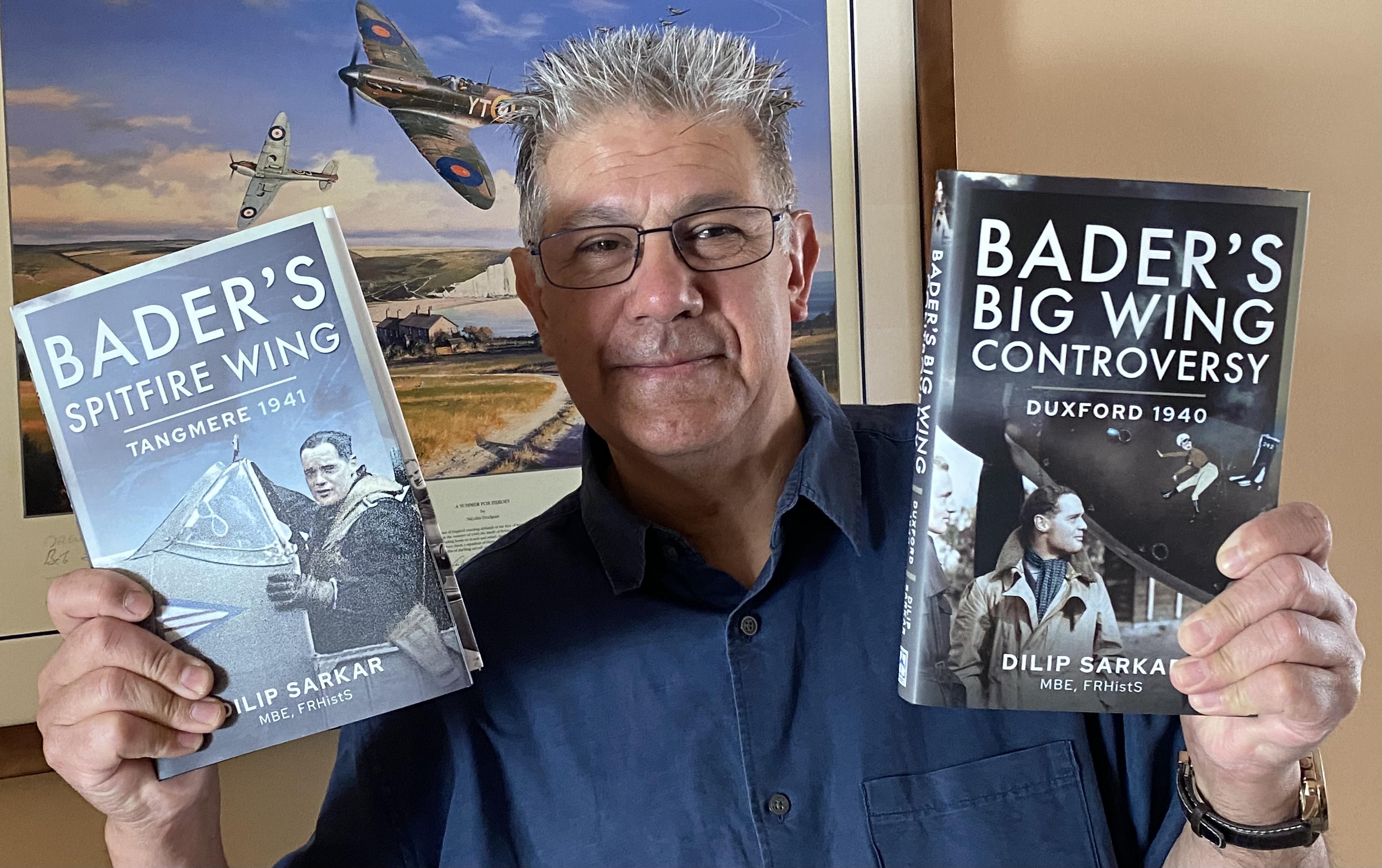

Author guest post from Dilip Sarkar MBE.

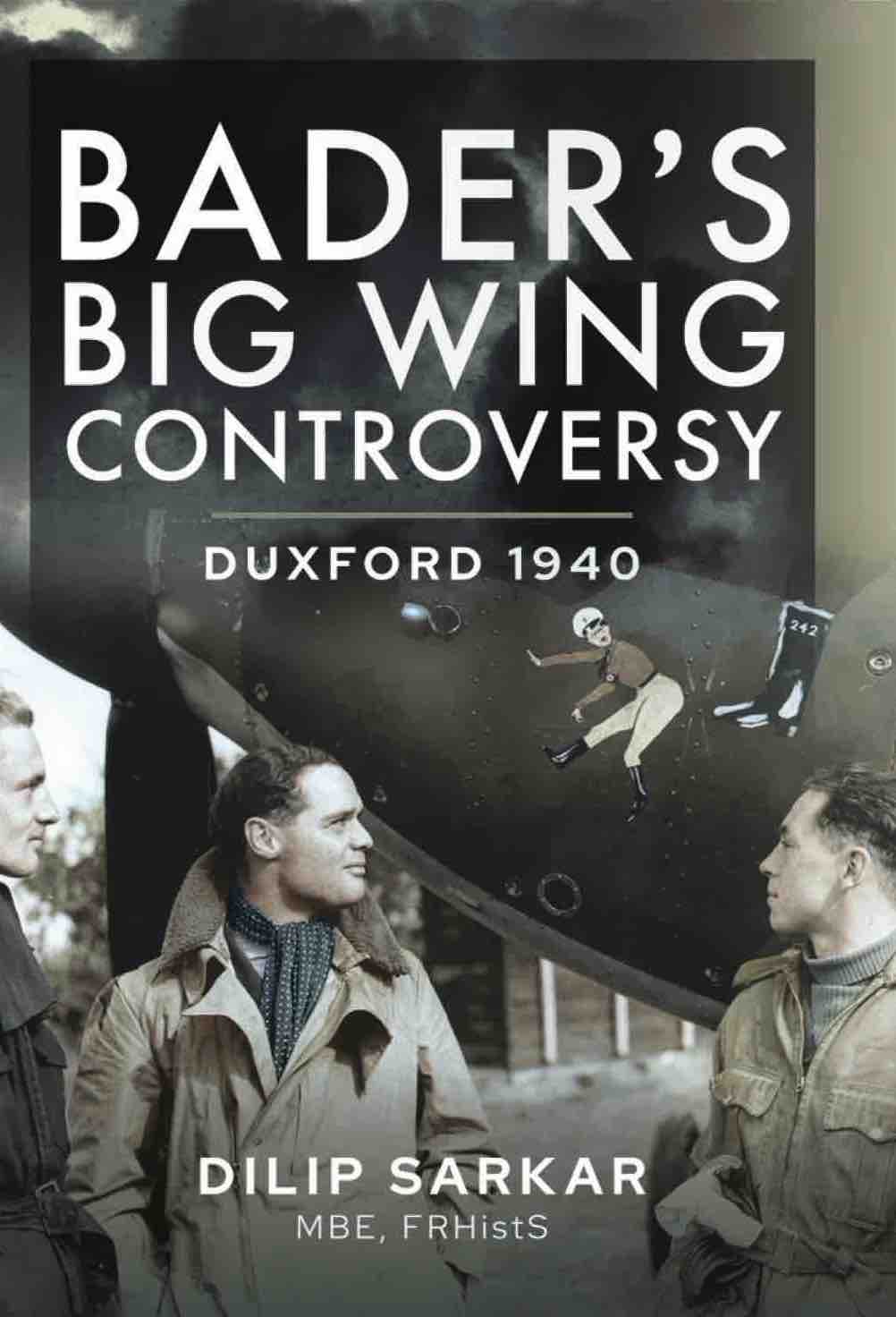

In my last blog, we talked about the misguided argument over tactics that broke out in the Battle of Britain, arguably initiated by the legless Douglas Bader, which saw certain officers of air rank and politicians support the view that mass fighter formations were the best way of meeting the enemy – which led to a change at the top in Fighter Command and tactics, going forward, that were based upon a flawed principal. All of this, in fact, is well-covered in my recent Bader’s Big Wing Controversy: Duxford 1940. Now, we have the sequel to that book, Bader’s Spitfire Wing: Tangmere, 1941, dealing with that heady summer of relentless fighter operations over north-west France.

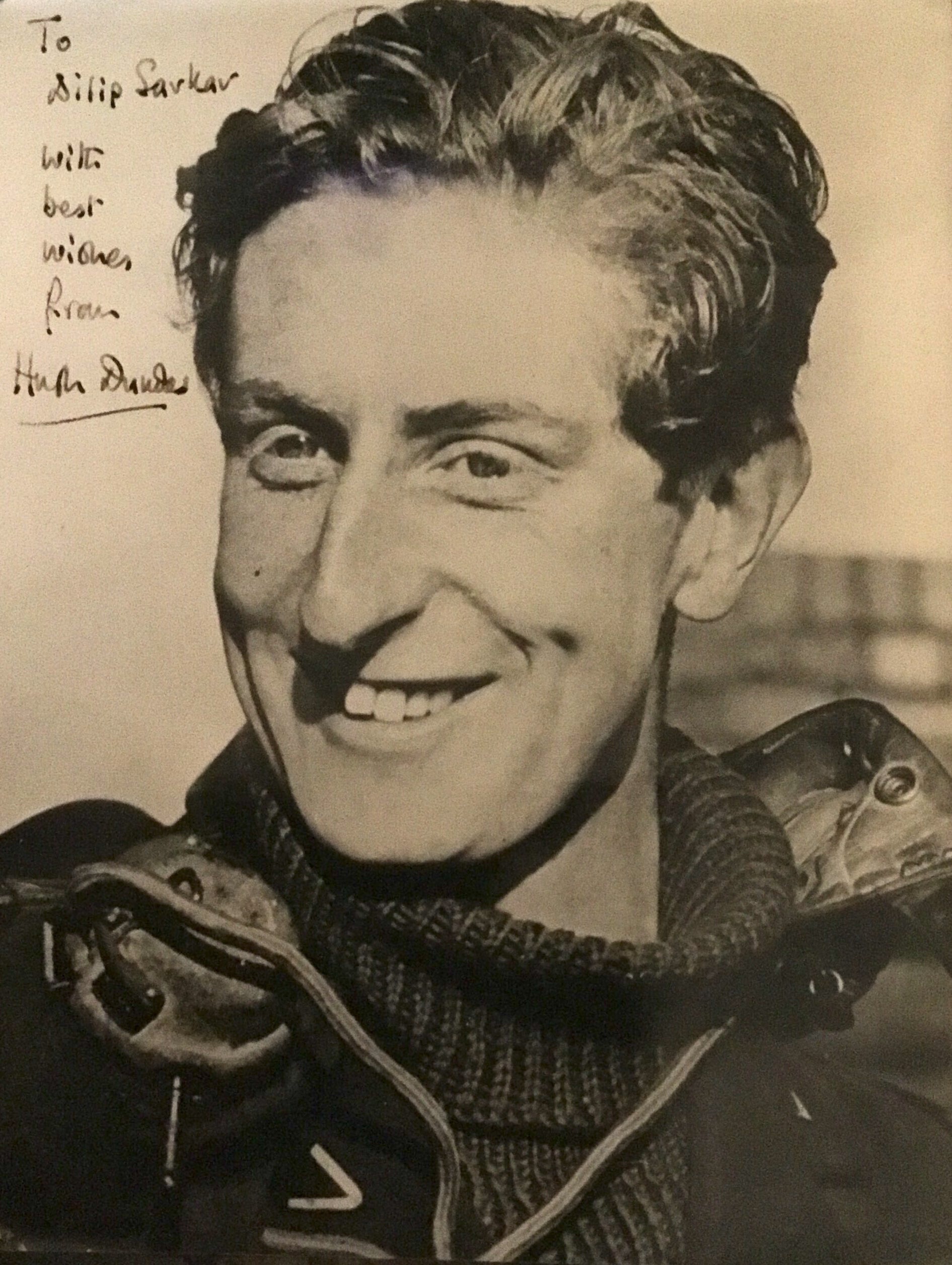

In March 1941, the new post of ‘Wing Commander (Flying)’ was created, the ‘Wing Leader’s’ job revolving simply around the operational effectiveness of his wing. Amongst the first appointments was Wing Commander Douglas Bader DSO DFC, who was even given a choice of stations: he chose Tangmere, that famous fighter station near Chichester, on the South coast. Bader chose to lead the Tangmere Wing at the head of Squadron Leader Billy Burton’s 616 Squadron, based at Westhampnett, usually flying in ‘Dogsbody Section’ with Flying Officer Hugh Dundas, Pilot Officer Johnnie Johnson, and either Sergeants Alan Smith or Jeff West. As the weather improved, the more relentless became the pace and tempo of operations – which was the way the swashbuckling Bader liked it. Day after day, the Wing was in action over France – but across the Channel was a formidable enemy.

This was, of course, a reverse of the Battle of Britain scenario, with the Spitfire – intended as a short-range interceptor – pressed into an offensive, escorting, role, with two sea-crossing per operation. Whilst, unlike German pilots brought down over England, Allied pilots had the advantage of possibly receiving assistance from French patriots and the resistance network if shot down, a prison camp was a more likely outcome. Flying and fighting over the sea is incredibly dangerous, and many pilots from both sides would simply be engulfed by it. The Germans, in fact, had the advantage. There were no targets in north-west France of strategic importance to the Germans, and the battle they were now fighting perfectly suited their fighter, the Me 109, which, like the Spitfire and Hurricane was designed and intended to be a short-range defensive interceptor. The Me 109 was an excellent aircraft with high-altitude capacity, and having a fuel-injected engine meant its great performance strength was in the dive, because the engine, being unaffected by gravity, unlike the RAF fighters, kept going. Consequently, the German fighters climbed to great heights and watched and waited for the right moment to attack the great RAF formations, which they pounced on in fast diving ambushes. Gone were the days of First World War dogfights, really, and time and time again the German fighters would appear as if from nowhere in these high-speed diving passes, fire, then away.

When Flight Lieutenant Archie Winskill was shot down and baled out over Calais, his ‘Home Run’ across the Pyrenees was facilitated by the resistance, who asked him why there were more Spitfires crashing in France than Me 109s? ‘I had no answer’, said Sir Archie many years later. At the time, Fighter Command’s combat claims were enormous, frequently, we now know, being so far removed from actual German losses as to be pure fantasy. There were many reasons for this, largely connected with the confusion of battle and fighting over enemy territory, because the claims were made in good faith, but, nonetheless, were inaccurate and therefore again misinformed strategy, as had the Big Wing’s inflated claims during the Battle of Britain. The truth is that the Germans won the day-fighter air war over north-west France in 1941 by between 2/4:1 – which is a far cry from the impression given by romantic post-war yarns like Paul Brickhill’s Reach for the Sky.

Into this maelstrom Wing Commander Bader led his Tangmere Wing constantly throughout that summer of 1941. Unfortunately, the RAF would lose many highly experienced fighter leaders and pilots, either killed, missing or captured, men Fighter Command could ill-afford to lose – ultimately, ironically, including Wing Commander Bader. Exhausted but refusing rest, Bader’s reactions were slow and led the Wing into a trap over St Omer on 9 August 1941, and ended up getting shot down and captured. What happened next is a controversial story all of its own, which I have researched since realising what happened back in 1995. My fascination with the Big Wing Controversy of 1940 and the consequences of it in 1941, in fact, led me on an incredible journey during which I came to know all the main characters in this drama as friends, including Air Marshal Sir Denis Crowley-Milling, Air Vice-Marshal Johnnie Johnson, Air Commodore Sir Archive Winskill, Group Captain Sir Hugh Dundas, Squadron Leaders Sir Alan Smith, ‘Nip’ Heppell, Jeff West and ‘Buck’ Casson – to name but a few, and on the German ace Major Gerhard Schöpfel. Groundcrews too, on both sides, contributed their experiences, as I feverishly recorded their memories. All these years later, those unique first-hand accounts combine in Bader’s Spitfire Wing with the official records and a detailed analysis of those far-off but deadly combats – supported by a unique set of photographs, most originated in the personal albums of the survivors. In truth there could never be another book or project like it, because all of the players are sadly now deceased.

My previous blog explains the Big Wing Controversy: –

https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/blog/baders-big-wing-controversy-duxford-1940/

And Bader’s Big Wing Controversy: Duxford 1940 can be ordered here: –

https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/Baders-Big-Wing-Controversy-Hardback/p/20171

So, with publication of Bader’s Spitfire Wing: Tangmere 1941, we now have the full story: –

https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/Baders-Spitfire-Wing-Hardback/p/21092

It really has been a great thing to do, to research these books and actually speak to those who were there fighting for their lives in those cramped, cold Spitfire and Me 109 cockpits high over France all those years ago – and now you can read the whole story in these two detailed books.

Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS, 11 April 2022

More on Dilip’s website.

And on Dilip’s YouTube channel.

Follow Dilip on Facebook and Twitter.