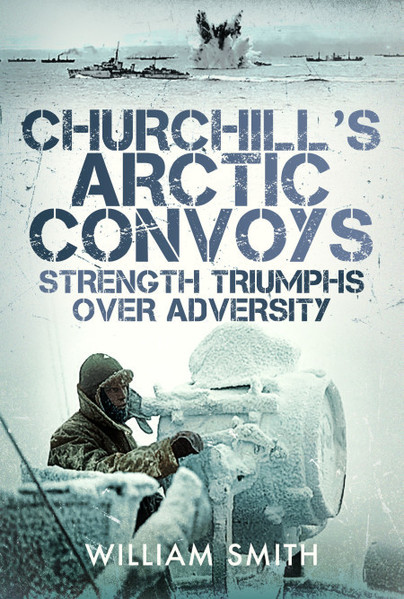

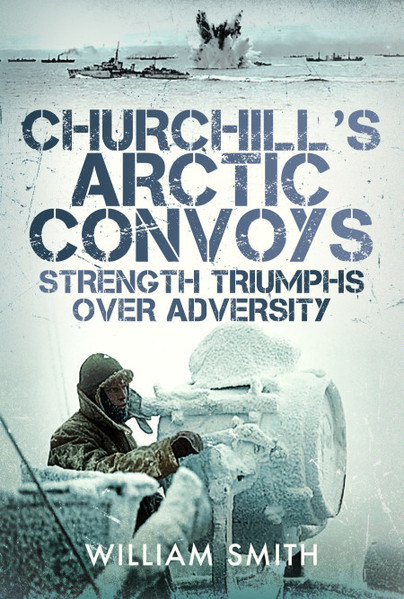

Author Guest Post: William Smith

INTRODUCTION

The Russian (or Arctic) which ran between August 1941 and May 1945), have in recent years become the subject of numerous publications and documentaries. The advent of the internet has also enabled wider access to a range of digitised archive material held in British, American and German official records, together with other semi-official and eye-witness accounts. Conversely the proliferation of media on the subject has encouraged the spread of poorly researched and unreliable information which has gradually gained acceptance as established fact.

WHY I WROTE CHURCHIILL’S ARCTIC CONVOYS

My father who served in the merchant navy sailed in two north Russian convoys but like many of his contemporaries spoke little about his experiences. The publicity surrounding the campaign to secure recognition for those who served through award of the Arctic Star motivated me to learn more about the subject.

THE RESEARCH PROCESS

The first publications I consulted lacked details of the full chronology, some focused on particular years or events leaving gaps in the narrative and questions unanswered. I then turned my attention to a range of archive sources which enabled me over a period of years to piece together a comprehensive account of events. These sources included British, German and American political and naval archives including the National Archives, Hansard, War Cabinet Minutes, Admiralty War Diaries, a range of German Naval War Diaries, and USN archives.

Examining the original Admiralty convoy held in the National Archives at Kew proved a particularly rewarding and emotional experience Going through the official Admiralty files, turning the pages of contemporaneous signals, reports and directives of the day, some signed by Churchill himself is to experience in the moment a tangible sense of the history of the convoys.

From this research I was able to compile a narrative account for every convoy, some more eventful than others, which identified their outcomes and significance within the wider national and international context. The process however generated some 440,000 words of text which to preserve continuity and context was then divided into two volumes, describing the operational and strategic aspects of the convoy programme. Initially I had no thought of publishing the results, however as the scope of the manuscript expanded and developed and new facts emerged it seemed the contents might provide a useful reference and baseline for a wider audience interested in learning more about the detail of the Russian convoys.

THE FINISHED BOOK

Churchill’s Arctic Convoys offers a composite “tour d’horizon” of the convoy programme between August 1941 and May 1942. This includes details of the sailing programme, size and composition of the convoys including naval escorts, the threats encountered losses sustained. It demonstrates the convoy programme did not run continuously, or at regular intervals during the war; the frequency and size of each convoy being determined by wider political and military constraints including competing strategic military objectives and strength of the German opposition, but ran in a number of distinct phases, or cycles, mirroring the effects of these constraints.

SALIENT FINDINGS

The research and subsequent analysis revealed a number of apparent discrepancies in previously published claims and statistics, some based on incomplete data or unquantified generalisation. These include:

- The number of convoys: Only 75 out of 78 convoy sailings carried supplies, (40 to Russia, 35 return). Many of those ships which returned were in ballast and carried no cargo.

- Frequency of convoys. Although Churchill promised Stalin a convoy every two weeks the programme was interrupted on several occasions for weeks or months at a time by wider political and military constraints leaving the promise unfulfilled.

- The number of sailings. Claims about 1,400 merchant ships delivered essential supplies to the Soviet Union were found to be incorrect. There were 764 sailings to north Russia and 685 return, undertaken by 527 of merchant ships.

- Merchant shipping losses. The number of merchant ships lost is commonly quoted as 84 but losses in north Russia and independent sailings increase that number to 100 (excluding naval auxiliaries)

- Merchant shipping loss rates. Historically Official British Government figures reported merchant shipping losses as a percentage of the 1,400 sailings, i.e 6% when the real loss rate based on 100 merchant ships was 19%.

- Royal Navy Losses Similar sources reported 18 Royal Naval warships sunk. The research now confirms a total of 21 were lost and 5 five badly with more than 2,000 personnel killed.

- The Allied contribution. Twice as many American owned ships sailed with the convoys than British and sustained the majority of all losses. Conversely very few Russian merchant ships participated after late 1942, most then diverted to the Vladivostok route.

THE CHURCHILL DIMENSION

Churchill was the prime mover in initiating the aid programme, later involving the United States who progressively assumed the major shipping role. The maintenance of supplies to Russia remained one of his principal interests up to the end of the war, hence the choice of title “Churchill’s Arctic Convoys” . The sub title “Strength Triumphs over Adversity” was chosen to reflect the gradual shift in the military balance between British and German forces.

The source of the quote ‘The worst journey in the world’ attributed to Churchill, frequently encountered during my research could not be identified. Subsequent consultation with recognised authorities on Churchill confirmed this quote to be wholly unsubstantiated and myth – an example where frequent repeated references on Internet have promoted acceptance as truth.

WHAT WAS OMITTED

The redaction of the original draft narrative led some readers to criticise the lack of depth of detail and omissions from their perspective. These included:

- lack of assessment of cost-effectiveness of the convoys and effectiveness of other supply routes together with lack of information on convoy cargoes or what the Russians did with the supplies.

- failure to describe in detail the Battles of the Barents Sea and North Cape and attempts to sink the Tirpitz; the contribution of aircraft carrier operations, and arrangements for convoy organisation and defence,

- insufficient focus on activities of Naval close escort and cover forces, their increasingly sophisticated weapons and tactics, and omission of Fleet Air Arm operational losses in carrier operations.

- omission of personal narrative accounts by survivors.

In fact many of these areas were addressed in the original draft manuscript which at 250,000 words greatly exceeded the publisher’s house rules and had to be edited out, others simply fell outside the scope of the narrative which arguably still offers a more comprehensive account and analysis of the operational aspects of the convoys themselves in a single source than available elsewhere.

CONCLUSION

It was never my intention to deliver a dramatized account of events but rather to provide myself and the reader with an accurate chronicle of the convoy programme and analysis of the actual outcomes for future reference and promote a more informed understanding of the subject.

Order your copy here.