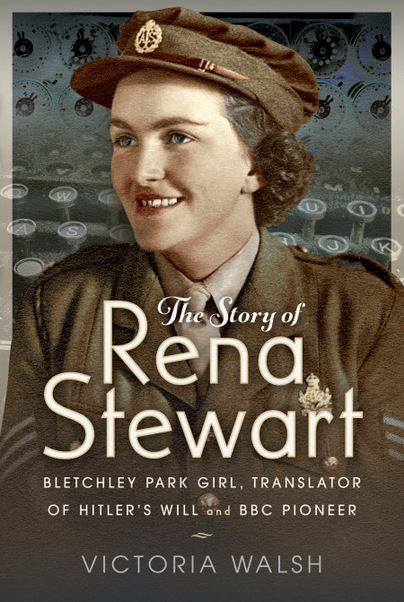

Author Guest Post: Victoria Walsh

Bletchley Park ‘Plus’: One Woman’s Century of Service

Bletchley Park Girls are beloved by Britons, and it’s unlikely that we’ll ever tire of their stories. With so few BP veterans still alive, it seems unlikely that many new stories will be told now. But what if there were a new one, and what if, for that Bletchley Park Girl, the Park was just the start? Rena Stewart (1923-2023) served at Bletchley Park then went on to translate Hitler’s will, and to blaze a trail for women at the BBC World Service. Rena wasn’t one to show off, but her contributions to history, and to women’s advancement in the media, are certainly worth celebrating.

Rena’s story starts in Fife, Scotland, with her mother and eight aunts who were among those cruelly referred to as ‘the two million surplus women of World War One’. Five of them never married; most of them became teachers. Rena never married, either, but she knew from an early age that she’d ‘rather scrub floors than be a teacher’! A different path lay ahead for her, with at least five opportunities to make a little bit of history.

- War service

Rena studied languages at St Andrews University, believing that this would give her access to ‘a whole new world’. Little did she know! On graduating, in 1943, she decided to ‘do something about the war’, and her German language skills got her selected for Bletchley Park. There, she worked on secret German messages. Her role was essentially to make decoded German text readable, and note any actions taken, so that the messages could be analysed by Intelligence colleagues. It was dull, taxing work, sitting at a typewriter for long hours, but as it turns out, typing was important to winning the war. Plus, she had a splendid social life and made many firm friends.

- Post-war justice

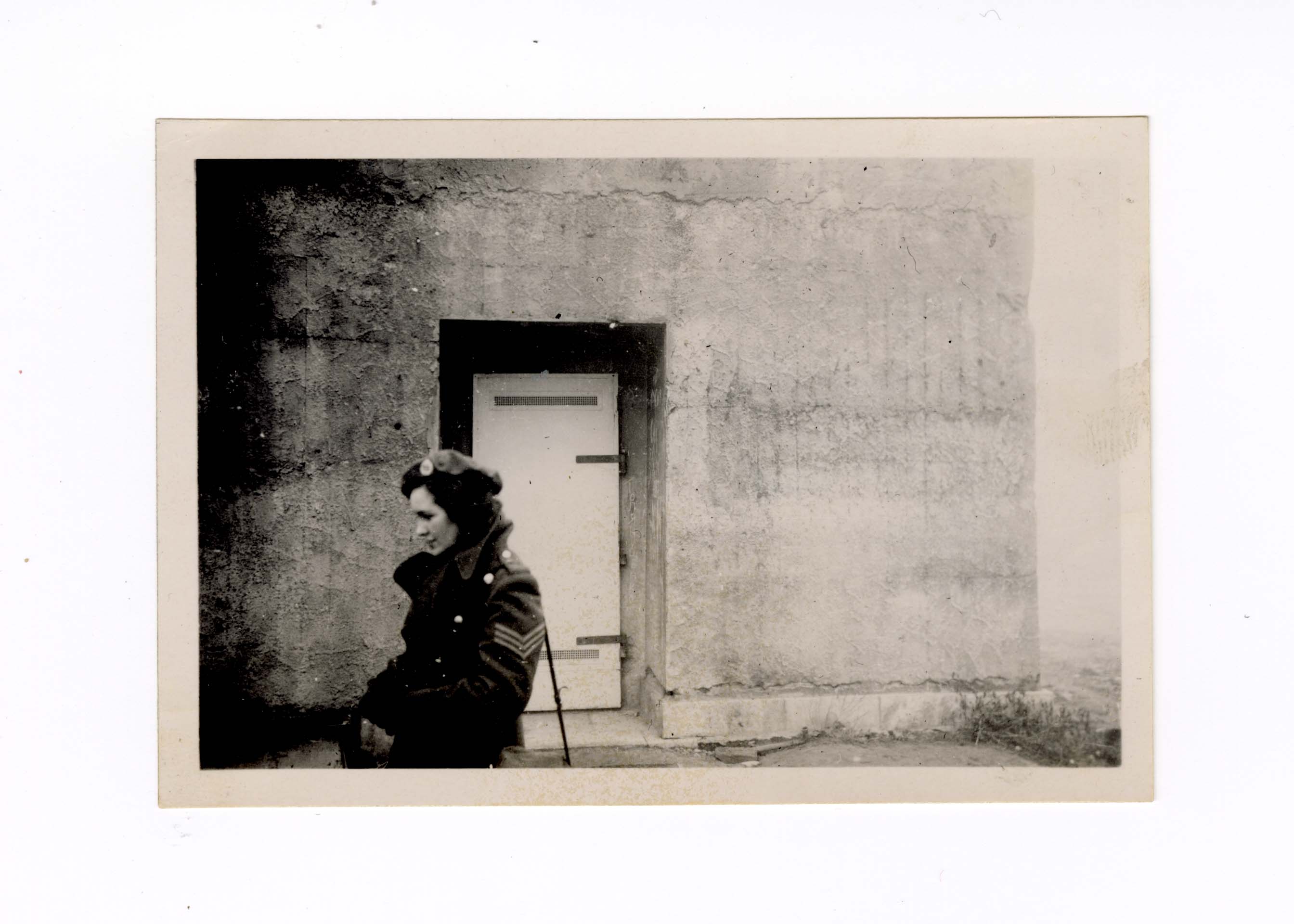

When the war ended, Rena and her Bletchley Park friends hadn’t been in the Army for long, so they weren’t demobbed immediately. Instead, they were sent to serve in Germany. After an epic journey across war-torn Europe, they arrived at the Bad Nenndorf interrogation centre, near Hanover. Their task was to translate the statements of captured Nazi officers and industry leaders. This was serious work, pertaining to life and death. It was also pertinent to security, in the unstable post-war period, and to the Nuremberg Trials. The interrogations were done by German Jewish soldiers. Rena wasn’t present at these, but she did visit one prisoner. This one was a fantasist who had exaggerated his involvement with the Nazis but was going to be convicted of being a Nazi spy nevertheless. A death sentence loomed; her male colleague (the interrogator) burst into tears, and Rena never forgot either man.

- Translating Hitler’s will

One day while Rena was in Germany, her boss came into the office that she shared with her Bletchley Park friend, Margery. He gave them a special, top-secret task: to translate Hitler’s will. This had been found after being spirited out of Hitler’s bunker, a day before he committed suicide. The women took great care to make the translation perfect, and they didn’t breathe a word to their colleagues. It was ‘quite a remarkable thing to have done,’ she admitted. Rena didn’t know what had happened to their work, until 1947, when she found their translation in the best-selling book The Last Days of Hitler, by Hugh Trevor-Roper. Other translations were done too, but this proved to Rena that her and Margery’s was the ‘definitive’ version. Modest as always, she reflected that she had felt ‘a certain amount of pride’ that it had been ‘an acceptable piece of work.’

- Cold War

Rena had had a good war, but what she had actually always wanted to do was to work in the media. Returning to the UK, she struggled to find a job. She couldn’t mention her secret work experience, and in any case, the returning men wanted their jobs back. Finally, she found a lowly position as a clerk at the BBC World Service and was able to work her way up from there.

Still, war was never far away. The Cold War was now on, and Rena was doing her bit again. In the German Department, she sent ‘propaganda stuff’ to East Germany, and Shakespeare and Ibsen plays to West Germany. However, she emphasised that ‘We weren’t setting out to do propaganda – we were setting out: this is the way we do things, and why don’t you come along with us?’ She then spent 10 years listening in to Russian radio broadcasts, with BBC Monitoring. She may also have played a role in the Cuban Missile Crisis, which the BBC helped to resolve by conveying messages from Khrushchev to Kennedy.

- Women’s advancement in the workplace

Perhaps the most significant challenge for Rena at the BBC was to overcome the workplace sexism of the day. She explained: ‘There was this idea that you couldn’t have a woman writing about disasters (earthquakes etc). What rubbish!’ Rena had dealt with Hitler, so she ‘conquered’ this challenge and eventually became the first female Senior Duty Editor (boss) in the newsroom. This was her dream job, and years later, she declared that ‘My greatest achievement has been getting people to recognise that a woman can be as good a journalist as a man.’

She certainly inspired her younger colleagues. One, Sally-Anne Thomas, was in awe of Rena’s combination of consummate journalism, a gentle smile and a will of iron. She said: ‘My generation of woman journalists realised that the more senior jobs were not beyond their reach, and I began to see that there was a place for me in that newsroom.’

Rena concluded – with her typical modesty: ‘I’d say I didn’t break the glass ceiling, but I made a few cracks!’ My conclusion is simply: what a woman!

The Story of Rena Stewart will be published by Pen and Sword History on 30 May.