Author Guest Post: Tony Buttler

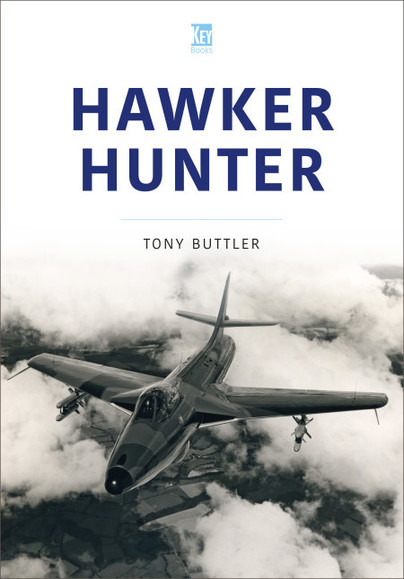

Hawker Hunter

One of the UK’s most famous combat aircraft, the Hawker Hunter has always been one of my favourite aeroplanes and it remains a most popular aircraft for many aviation enthusiasts. In appearance it has the style and elegance one always associates with the design team at Hawker Aircraft at Kingston, but it is also a sleek fighter aircraft with the imposing appearance of a powerful warplane developed to protect its country!

This new book, a revision of the author’s earlier volume in Key Publishing’s Combat Machines series, presents a general review of the Hunter’s long and quite complex career, since its maiden flight way back in 1951. The chapters cover Design and Development, UK Service, Single-Seat Versions, Two-Seat Versions, Experimental Hunters, Overseas and Export Service, Combat History, and Display Teams. The text is accompanied by a wealth of photographs, both in black and white and in vintage colour, some of which had never been published before prior to the release of the first edition. A good number of Hunters are still flying in private hands today, and numerous further airframes are held by museums in Britain and all over the world, so there is plenty of scope for anyone to view a Hunter close-up!

Over the years much has been written about the Hunter, but many enthusiasts may not be aware of certain elements of the story. So here are a few items that might be new to anyone reading this (note: P.1067 was Hawker’s project number for its new fighter design and was used until the name Hunter was bestowed).

- At one point the Hunter held the World Air Speed Record. In September 1953 Hawker test pilot Neville Duke set a new level speed record of 727.6mph (1,171km/h) flying over the county of Sussex (the record was broken again very soon afterwards by a British Supermarine Swift, a rival design to the Hunter). The aircraft used by Duke for the record was the very first P.1067 prototype (military serial WB188) specially fitted with afterburning/reheat to its Avon engine, a new pointed nose and certain other mods. As such it was designated the Hunter Mark 3 but, beyond the record itself, the extra weight and complexity and fuel consumption in fitting reheat, when the Hunter had been designed as a relatively simple day fighter (and not having a large fuel load internally), was not considered worthwhile, so WB188 remained the only Hunter so equipped in the UK.

However, in 1958 one of the 120 Hunters sold to the Swedish Air Force (where the aircraft was designated J 34) was also fitted with reheat and it was found that this reduced the aircraft’s time-to-height very considerably. Nevertheless, once again, this programme was abandoned because of the high fuel consumption associated with reheat.

-

The Hunter’s aerodynamics meant that the aircraft could never go supersonic in level flight, though in a dive it would pass through the ‘Sound Barrier’ with ease; as such it was classed as a transonic fighter. The team at Hawker did design and propose several different supersonic versions and one of these was taken up – but for only a short time! The was the P.1083 project which introduced a wing swept to an angle of 50° at the leading edge, instead of the 35° of the standard Hunter wing. The P.1083 was cancelled in 1953 before the prototype had been completed, but the redundant airframe was modified to become the prototype of the Hunter Mark 6 which introduced a more powerful 200-Series Rolls-Royce Avon engine. Sadly, a lack of space, and the fact that it never flew, prevented the inclusion of a detailed description of the P.1083 in the book.

-

Early single-seat fighter versions of the Hunter were powered by different engines – the Marks 1 and 4 by the Rolls-Royce Avon, the Marks 2 and 5 by the rival Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire. In addition, the Sapphire-powered machines were not built by Hawker, but instead by Armstrong Whitworth at Coventry. However, all of the two-seat Hunters, and the single-seat versions from the Mark 6 onwards, were fitted with Avons.

-

One area of aviation history which interests me very much are experimental and one-off designs and research aircraft, plus examples of standard (production) aircraft types modified for specific trials programmes. This could include the fitting of different engines or weapons, such aircraft now serving as test beds, or aerodynamic modifications of various forms. Some British fighter and bomber types were used extensively in this type of work, but quite a few Hunters were also employed in research roles. A chapter of the book is devoted to this subject, though readers wishing to know more may like to consult another of the author’s titles released in this Key Publishing series – Aircraft Engine Test Beds: British Jet Fighters and Bombers.

The author’s particular favourite here is the Hawker P.1109, three examples of the Hunter Mark 6 fitted with an extended and more pointed nose to house a Mark 20 air intercept radar, plus de Havilland Firestreak air-to-air missiles under the wings (though only one, serial XF378, would actually carry the weapon). No Hunters in UK service would ever operate with air-to-air missiles, but the P.1109 programme is a great example of how an aircraft’s capability might be upgraded. In addition, with its improved aerodynamics the P.1109 could easily outperform and outclass a standard Hunter Mark 6 at high altitude, and the three examples produced looked superb!

-

Since they were still relatively new, many withdrawn and retired ex-RAF airframes were refurbished by Hawker for sale abroad. In fact, for a period during the 1960s and 1970s Hunter exports gave the manufacturer a prolonged supply of refurbishment work. The aircraft was sold to a long list of overseas countries and at one point Hawker because frustrated with the scrapping of some RAF airframes because the firm knew that there was a market for these as well. It is worth pointing out that the Hunter was first ordered for the RAF to replace the UK’s first jet fighter, the Gloster Meteor. It would go on to replace the Meteor in the Belgian, Danish and Dutch Air Forces as well.

There are so many elements to the Hawker Hunter story and the book has managed to include the most important. I hope readers will enjoy it, and I also hope that younger enthusiasts in particular will find the book a stimulus to finding out more about this wonderful aeroplane, and indeed about aviation history in general!

Order your copy of Hawker Hunter here.