Author Guest Post: Simon Webb

Today on the blog we have a guest post from author Simon Webb. Simon’s new book, Secret Casualties of World War Two reveals one of the last secrets of the Second World War; the casualties which ‘friendly fire’ from heavy artillery inflicted upon British and American civilians.

…………………………………………………………..

At the heart of the artfully constructed narrative about the German bombing raids on Britain that we know today as the Blitz, lies a terrible secret; one which has been forgotten for many decades. Over 52,000 civilians were killed in Britain during the Second World War, assumed by most people to have been victims of German bombs. In fact, as many as half of the casualties were caused not by the German air force, but rather by artillery operated by the British army.

After the Germans bombed Britain in the First World War, by Zeppelin and aeroplane, it was realised that there was no real defence against air raids. Attempts to use heavy artillery to shoot down aircraft had proved futile. Indeed, it had been worse than futile, as the shells had done no damage to enemy aeroplanes but instead fallen to the ground and exploded; killing many civilians. As Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin so succinctly put it in 1932; ‘The bomber will always get through.’

In September 1940, a year after the beginning of the Second World War, German bombers appeared in the skies of Britain and began trying to break the country by destroying both the physical infrastructure and the also the ordinary person’s will to resist. Because no apparent attempt was being made to defend cities against the bombers, public morale plummeted and there was a real risk of mass flight from the cities, in search of safety in the countryside. To prevent this, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered artillery to begin a vast barrage across London and other cities. Shells weighing 80 lb (36.3 Kg) were hurled into the air above London by heavy guns and even the armoured turrets of battleships were positioned in and around the capital. Illustration 1 shows one such turret on top of Primrose Hill, near London Zoo.

H 32322

Part of

WAR OFFICE SECOND WORLD WAR OFFICIAL COLLECTION

War Office official photographer

Taylor (Lt)

The chances of actually hitting fast-moving aircraft with artillery in this way were negligible, but the roar of the guns firing over 10,000 shells a night was cheering and reassuring to the inhabitants of London. The idea was that the shells would explode near enemy aircraft, but many of the timing mechanisms were defective and according to some estimates half the shells only exploded when they came down in city streets. Not only were the shells not of the highest quality, neither were the men who were responsible for firing them. The best of the conscripts went to the fighting units of the army, navy and air force. Those who ended up in the anti-aircraft batteries tended to be those no other service wanted. Consider the 31st AA Brigade. Out of 1,000 recruits, 50 could not be used for duty because they were unsafe to be allowed out on their own. Another 20 were mentally defective and 18 had such physical disabilities that they were unfit for any other unit. It was such men who were responsible for making the most complex and intricate calculations to ensure that shells detonated at the correct height.

The first disaster came just 24 hours after the beginning of the Blitz on 7 September 1940, when the following day an artillery shell landed outside a café near Kings Cross, killing 17 people. From then on, the death toll from anti-aircraft fire was constant and unrelenting. Less than a week later, on 14 September 1940, members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service were sitting down to dinner at the Mansfield House Hotel in Lee-on-Solent where they were billeted. A shell fired by artillery in Portsmouth flew through the window of the dining room and exploded, killing 10 of the young women. According to some experts working on the proximity fuse in the later years of the war, at least as many civilians were killed by artillery fire during air raids as died from enemy bombs. In the Midlands district of Tipton, for example, 23 civilians were killed during air raids during the Second World War. Eleven of these deaths were caused by German bombs, but 12 died during a single incident on 21 December 1940, when a wedding celebration was taking place in a pub in the village of Tividale. An artillery shell weighing 28 lb (12.7 Kg) was fired from nearby Rowley Hills and sailed down the chimney of the building where the party was being held. The bride was killed, the bridegroom lost both legs and 11 other guests died. This shell came from a 3.7 inch gun of the kind seen in Illustration 2.

The number of injuries and deaths from anti-aircraft fire was no secret during the war. Deaths from the British artillery were widely reported in both national and provincial newspapers, despite the censorship operating at that time. On 29 March 1944, for example, the Western Mail reported that;

‘Anti-aircraft shells, one of which exploded in a crowded factory, killing 12 people, including seven women, and injuring as many more, were the chief cause of damage during activity over the South Wales coastal area on Monday night.’

The great irony of the whole business was that hardly any aeroplanes were actually shot down by the artillery which wrought such havoc in the cities of Britain. General Frederick Pile, the officer in overall command of the anti-aircraft defences, calculated that his men would have needed to fire 20,000 artillery shells to have a realistic chance of shooting down a single aeroplane.

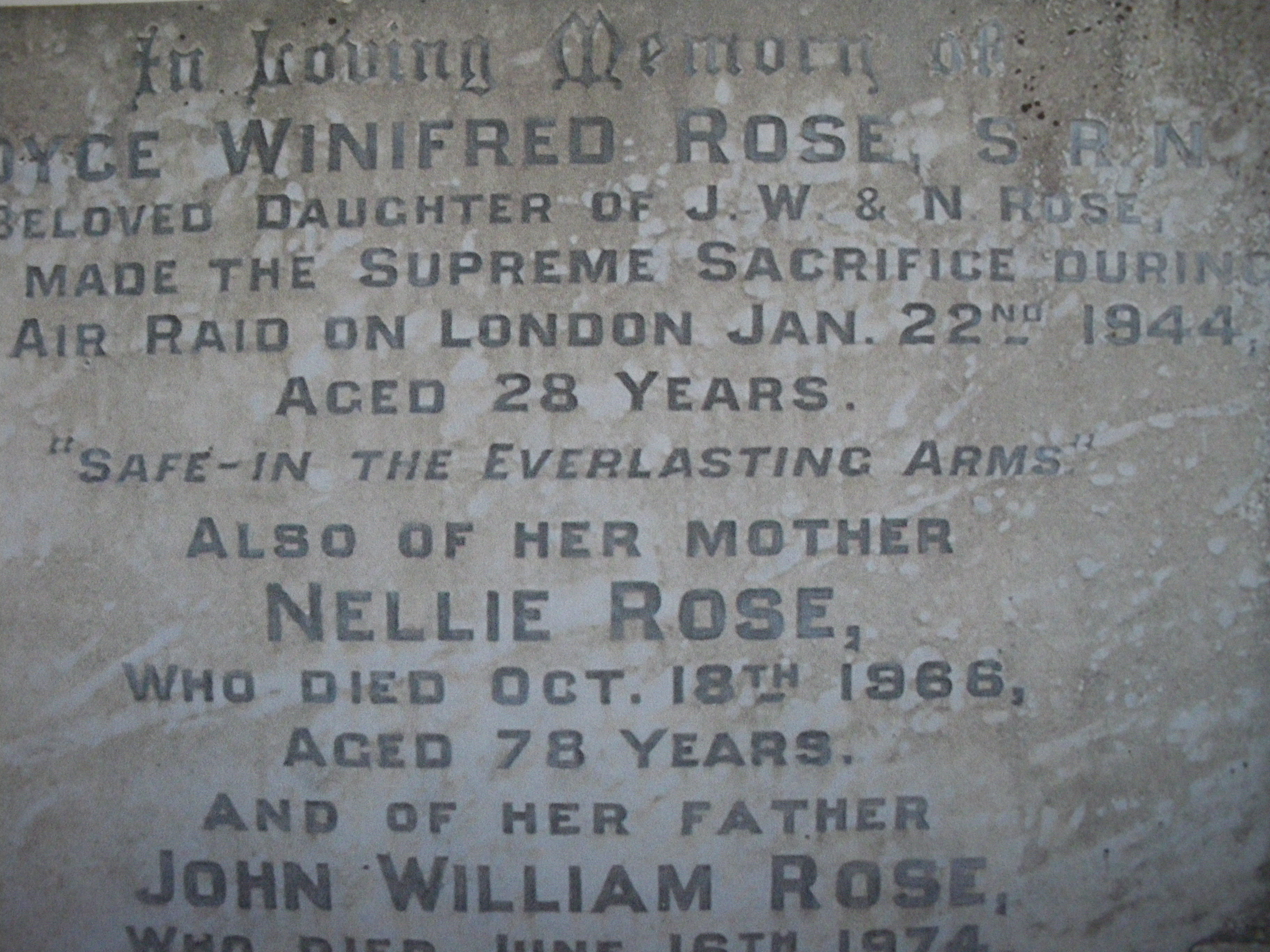

The many thousands of men, women and children in this country who died at the hands of their own army have now been almost wholly forgotten. Perhaps we prefer to remember them as heroic martyrs, whose lives were lost in a noble cause. Illustration 3 suggests that this might be at least part of the explanation. It shows the grave of 28 year-old nurse, Joyce Rose. According to the inscription, she ‘made the supreme sacrifice’ during an air raid in 1944. She was actually killed by when a British shell struck Bexley and Welling Hospital during an air raid on 22 January 1944.

Secret Casualties of World War Two is available to order now from Pen and Sword Books.