Author guest post: Kim Thomas

Elizabeth White: a story of murder and madness

It was a December morning in 1889, and 38-year old Elizabeth White was at home with her four children: Joseph (6), George (5), Mary (3) and baby John. Her husband, also Joseph, had left for work at about 10 o’clock. As a coachman to a wealthy family, his job involved driving his employers in all weathers, as well as caring for the horses and keeping the carriage clean.

Joseph and Elizabeth lived in Wimpole Mews in Mayfair. Joseph’s employer, a rich widow named Marianne Dunn, lived nearby in Harley Street, in a beautiful Georgian townhouse. These days, Mayfair’s mews houses are highly sought after, but back in the nineteenth century, the coachman’s accommodation consisted simply of two rooms above the stables. The windowless back room served both as the sitting room and as the children’s bedroom.

Elizabeth wasn’t the only adult at home that day. With her was a woman named Mary Deeley. Shortly after John’s birth in July, Elizabeth had started to behave oddly, becoming depressed and rambling, and Joseph was sufficiently concerned to move her, in September, to a private asylum in Bethnal Green. It’s unlikely that this is something he could have afforded on his own wages, so it’s possible that Marianne helped pay for Elizabeth’s keep. Like Marianne, Joseph and Elizabeth were Catholics at a time when Catholicism was still frowned upon, and she seems to have taken a keen interest in his family’s wellbeing.

While at the asylum, Elizabeth was depressed enough to attempt suicide, but her family wanted her home, and she was discharged on 10 December. Joseph – or perhaps Marianne – had hired Mary to keep an eye on her and look after the children. Four days later, after helping Mary wash and dress the children, Elizabeth took the three older siblings into the sitting room and locked the door.

Five minutes later, Mary heard screams. Unable to open the door, she fetched the Dunns’ butler, William Gibbons, who forced the door open. There they saw the two boys, Joseph and George, lying side by side on the bed. Elizabeth was trying to strangle George with a dark blue silk handkerchief, and had one hand on Joseph’s mouth. Gibbons was able to pull her away, saving George. He was too late for Joseph.

When a police officer came to the house, Elizabeth told him that if she hadn’t been interrupted, she would have killed all four of her children.

After her arrest, Elizabeth was taken to Holloway prison. At her Old Bailey trial in January 1890, two doctors testified that she was not of sound mind on the day of the murder, and the jury returned a verdict of “guilty, but insane”. Elizabeth was sent to Broadmoor to be detained at Her Majesty’s pleasure.

Broadmoor, Britain’s first asylum for criminal lunatics, had opened in 1863 in Crowthorne, Berkshire. Of the 500 patients, about 100 were women, and many had similar stories to Elizabeth. Roughly two-thirds of the asylum’s patients had been sent there after committing a serious crime, while the rest were convicts who had been transferred to Broadmoor after going insane in prison. About three-quarters of the women in the first group had committed murder, in almost all cases of their own children. The cause was often what was then called “puerperal insanity” – a term that covered the conditions we would today know as postpartum psychosis or postpartum depression.

Child murder was a very common crime in Victorian England – much more common than it is today – and many of those murders were committed by mothers. In the 1860s, half of all homicides consisted of mothers killing their own children. It was most likely the strain of repeated childbearing combined with desperate poverty that drove women to this extreme act, though in some cases there was the added stigma of illegitimacy. Most of those women ended up in prison rather than Broadmoor: the capital sentence was rarely passed, probably out of compassion. Where the dead child was a newborn, juries sometimes found the mother guilty, not of murder, but of “concealment of birth”, a lesser charge that carried a sentence of only two years.

Broadmoor, a large redbrick building, was set in 300 acres of gardens, pleasure grounds and farmland. Most of us think of Victorian asylums as cruel places with harsh regimes of cold baths and straitjackets, but Broadmoor was very different. Its superintendent, David Nicolson, was a compassionate man who treated his patients first and foremost as human beings: as well as beautiful grounds to walk in, they had a day room where they could play backgammon or cribbage, read books or play the piano. Nicolson also brought in entertainers from outside to perform plays and music, and patients were allowed visits from family. In 1891, Marianne and her adult children moved to Woolley Hall in Maidenhead, just a few miles from Broadmoor. She took her servants with her, so it’s likely that Joseph was able to visit his wife.

There were no treatments at Broadmoor – no medication or therapy. But some patients nonetheless recovered enough to be sent home, and this is what happened to Elizabeth. After only four years, she was discharged, this time to the small cottage, attached to Woolley Hall’s stables, where Joseph and the children lived. There, she settled back into normal family life until one evening in May 1902 when she went out for a walk and, crossing the railway line, was hit by a goods train and killed. Although it may have seemed like suicide, Elizabeth had shown no signs of being depressed, and the inquest jury recorded a verdict of accidental death. She was only 50.

Her three surviving children had mixed fates: John, only a baby when Elizabeth was sent to Broadmoor, was killed in the First World War, aged 25. Mary married, but died at the age of 46. George – who so narrowly escaped being murdered by his mother – married, emigrated to Canada and had four children. His descendants live there still.

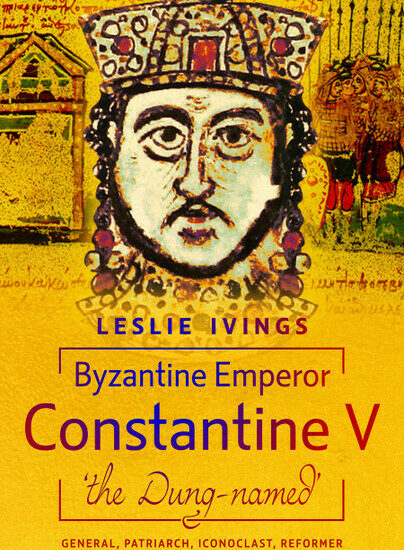

Broadmoor Women is available to order here.