Author Guest Post: Jan Merriman

Jane Austen’s aunt Philadelphia brought the world to the impressionable young Jane’s Hampshire home and echoed in her novels thereafter.

Who was Philadelphia Hancock and why was she significant in Jane Austen’s life and work?

Most Austen enthusiasts know of Jane Austen’s favourite cousin, and later sister-in-law, the comtesse Eliza de Feuillide, for whom Jane developed a great admiration and affection. Born Elizabeth Hancock, she became a French countess. But how did this exotic flower come into the provincial bloodline of the Austen’s? The answer lies with her mother, Philadelphia Austen, Jane’s paternal aunt.

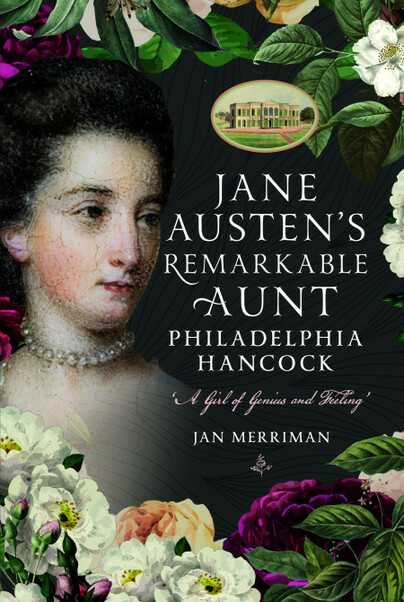

This exquisite portrait miniature of Philadelphia is now held in Jane Austen’s House in Chawton, Hampshire. It shows her as attractive and elegant, painted when she was 38, and designed for a ring for her husband to wear.

Philadelphia was the elder sister of Jane Austen’s father George, born in Tonbridge in Kent in 1730, the daughter of a surgeon. The children were orphaned when they were young, and sent to live with relatives. George and Philadelphia remained close throughout their lives and Philadelphia was a regular visitor to the Austen home in Steventon where Jane Austen grew up.

My interest in Philadelphia was piqued when I read a paragraph or two about her life story. It was fascinating. But very little research had been done further. Philadelphia was like many women of history whose lives have been neglected, the validity of their experiences denigrated, and marginalised from historical versions of great events. Their stories cry out to be told. And Philadelphia’s life story uniquely influenced Jane’s works.

Jane Austen’s early fiction, Catharine or the Bower and the story of her aunt Philadelphia

In Catharine or the Bower, a work written in 1792, just after the death of Philadelphia, and probably while her daughter Eliza was living with the Austen’s in Steventon, there are specific references to Philadelphia’s real-life experiences in the young Jane’s telling of the tale of orphaned children reluctantly taken in by relatives and of one of the girls being sent out to Bengal for an arranged marriage. There are also echoes of Philadelphia in the characters of Fanny Price, Lady Susan, Mrs Dashwood, Mrs Jennings and of Eliza especially in Mansfield Park written in 1813 in the months after Eliza’s death. But beyond those connections to Austen’s work, Philadelphia’s life is worth examining in its own right, for what it tells us about the lives of such women in eighteenth-century England; the kind of young women her niece fictionalised and brought to life in her novels.

Philadelphia as a millinery apprentice in Covent Garden

After living with wealthy cousins till she was 15, Philadelphia was apprenticed to a Covent Garden milliner for five years. Like thousands of other young people at the time who flocked to the burgeoning West End of London, Philadelphia, with no immediate family to provide for her, had to find a future for herself. Remember the enigmatic Jane Fairfax in Austen’s novel Emma? Orphaned and brought up as a companion in a well-to-do family, Jane Fairfax was given a good education so she could earn her living as a governess. A trade was the only option for Philadelphia. Would she have been happy there? Was it all back-room drudgery or were there young companions, a caring mistress and a chance to see a more exciting world opening up to her?

She joins ‘the fishing fleet’ and is off to India

After completing her apprenticeship, Philadelphia decided to take the journey out to India, and to an arranged marriage. The prospective husband was Tysoe Saul Hancock, a surgeon in the employ of the Honourable East India Company. Why did she go? She may have thought, like Charlotte Lucas in Pride and Prejudice that marriage was ‘the only honourable provision for well-educated young women of small fortune, and however uncertain of giving happiness, must be their pleasantest preservative from want’. And perhaps for the thrill of it all, the difference, and the excitement.

Eleven eventful years in India.

Six months at sea with eleven other young women with a similar mission, it was a risky voyage. She at last arrived at one of the East India Company settlements on the west coast of the sub-continent, Fort St David. She married Surgeon Hancock six months later and lived the comfortable expatriate life of servants and leisure. Her friends admired her, she was kind and caring and wrote regularly to her brother George back in England. Were her letters read aloud to the family? She wore the fabulous silks and shawls of India and the famous Attar of Roses perfume. But something was missing. After eight years of marriage there had been no children: no pregnancies, no miscarriages, nothing. It seems from a letter between mutual male friends that Surgeon Hancock was not able to give her children.

Flight from Fort St David and a fateful meeting in Bengal

Philadelphia and her husband lost everything when they had to flee Fort St David as the French laid siege to the East India Company settlement. Destitute, they had to start again in Kasimbazzar, and then Calcutta. There Philadelphia met Warren Hastings, a rising star in the EIC, brilliant scholar, who was on his way to Cambridge from Westminster School, and could have been anything, but like Philadelphia, orphaned and poor whose relatives sent him out to India at seventeen. He is 27, she is 33. Their connection holds throughout the next 33 years, despite being sometimes continents apart for years. Ten months after Hastings joins the Hancocks in Calcutta, where he and Philadelphia are seen to ‘live in intimacy’, her one and only child, Eliza, is born.

The birth of her only child, Eliza.

Was it Hastings’ or her husband’s child? The locals ‘gave the credit to Mrs Hastings’, a friend wrote. Was her husband complicit? In my book, Jane Austen’s Remarkable Aunt Philadelphia Hancock the evidence of Eliza’s paternity is explored. Her life is followed from its return to England, departure of her husband back to India, his death and her widowhood. Then its off to France, quite well-to-do now with a handsome endowment from Hastings, to see her daughter married to a French count. Or was he really? And then caught up by Revolution and the flight from France, to die in England.

The trajectory of Philadelphia’s life shows there is a place for women like her in the history of those times, a life uniquely hers, and a deserving place in Jane Austen’s family narrative.

Jane Austen’s Remarkable Aunt, Philadelphia Hancock is available to order here.