Author Guest Post: Jan Gore

The start of the Doodlebug campaign, 13-16 June 1944

The V1 flying bomb (known to the Germans as Vergeltungswaffe 1, Vengeance or Retaliation Weapon No 1) was a small jet-propelled and unmanned aircraft, a type of early cruise missile. Initially launched from ramps in the Pas de Calais, the V1s came in over the Channel at between 1,000 and 2,000 feet at speeds approaching 400mph. They proved a difficult target to intercept, much less to bring down and destroy. They were very effective weapons, cheap to manufacture and with no need for supplies of bombers, fighters or pilots to support their attack ; their single use meant no need for repairs or extra personnel. They did not demand good weather or a “bomber’s moon”, nor did they need to be launched under cover of darkness. They simply kept flying until they ran out of fuel. The noise would start as a distant hum, then grow to a deafening noise. If you were lucky, you would hear it gradually diminish as the V1 continued on its way. More ominously, it might stop with no warning; after a short interval the flying bomb would crash to the ground and explode. The wait seemed interminable to the listener, but in reality it would last little more than twelve seconds – not long to try to find the nearest shelter. You might be able to shelter under a desk if at work or behind a wall or in a doorway if you were in the open, but there would not be enough time to seek a public shelter … and probably not enough time to run from your home to your outdoor Anderson shelter, or anywhere else nearby.

Ironically it was the success of the Normandy landings after D-Day that made the start of the German V1 attacks unavoidable. The Germans had to go ahead with the V1 launches in an attempt to destroy British civilian morale. After all, what did Hitler have to lose at this stage? The V1s had been christened revenge weapons; now was the time for them to live up to their name. Soon after midnight on 13 June the Germans began by firing about thirty heavy shells towards Folkestone, damaging property; they also fired towards Maidstone, further inland. These were intended to divert attention from the imminent arrival of the V1s. Just after 04.00 there was an air raid warning over most of Kent. It was followed by an all clear, then almost at once there was another warning.

The flying bomb campaign had begun, with four out of the ten V1s reaching England.

It was still dark when, at 04.08, two men from the Observer Corps at Romney Marsh, Dymchurch, spotted “a strange shape, the size of a small fighter” making a noise like “a Model T Ford going up a hill”. They instantly identified it from the description they had been given two months before and telephoned Maidstone Observer Corps with the agreed code words “Diver! Diver! Diver!” Maidstone in turn relayed this to No. 11 Fighter Group at Uxbridge, who passed the report to Air Defence of Great Britain HQ at Stanmore. Whitehall was then notified; the long-awaited attack was finally under way.

The first flying bomb to land on British soil exploded at 04.13 at Swanscombe, near Gravesend. It fell on a field of greens and lettuces, leaving a shallow crater and badly damaging a house and a large area of crops. The noise it made was described as making cattle bellow with fear. The second landed at 04.20 in Sussex, near Cuckfield, narrowly missing a cottage near Mizbrooks Farm where a woman and her young children were living; she described “this sinister, eerie grunting noise”, followed by “the uncanny silence when the engine cut out and then the ear-shattering explosion, and the house shaking and shuddering”. The windows were blown out and all eighteen acres of the farm were “mown” by the blast, with the whole crop stripped to a uniform height. The fourth V1 crashed significantly later, at 05.06 in the garden of a large house at Platt, near Sevenoaks, killing a number of chickens and wrecking two rows of greenhouses.

The third was the only flying bomb of the four to reach London but did more damage than the other three put together. It exploded at 04.25 on the railway bridge over Grove Road, Bow. This carried the main line between Chelmsford and the LNER terminus at Liverpool Street. The V1 blocked all four lines over the bridge; it damaged a number of houses and there were casualties, some fatal. Six people were killed (their ages ranging from eight months to 55 years), the first of 6,200 such deaths that would be caused in the coming months. Thirty were injured, with ten people detained in hospital. 200 people were made homeless.

Initially there was the issue of deciding what had caused the blast. Was it a bomb or a crashed aircraft? By 06.15 the wreckage had been identified as a PAC (a pilotless aircraft) rather than a conventional bomb. Then there was a search for fragments, followed by the arrival of senior officials from the Ministry of Home Security to examine “it” in detail. There was a need to keep the attack secret from the Germans, so there was no reference to the raid in the morning papers. However, local and mainline railway tracks had been blocked, so thousands of people were aware a major incident had occurred. Their morning trains were diverted to Fenchurch St or stopped short at Stratford. Mainline services were affected as far away as Bishops Stortford and Cambridge, even though normal services were resumed by Friday evening of that week.

Over the next few days, the Germans worked hard to ensure that as many V1 sites as possible were fully equipped; fifty-three were made operational within the next two days. On 15 June Colonel Wachtel sent out new orders to his four subordinate commanders: “Open fire on Target 42 [London] with an all-catapult salvo” at 23.18, with a range of 130 miles, followed by sustained fire until 04.50 the next day, Friday 16 June.

This time the bombardment began promptly. By noon on 16 June, 244 V1s had been launched. There was the usual rate of attrition; forty-five crashed on take-off, destroying nine launch sites in the process and killing ten French civilians. Some of the rest went off course or simply disappeared, but seventy-three reached Greater London. Eleven were shot down over the capital; Flight Lieutenant Musgrave of 605 Squadron, flying a Mosquito, was the first pilot to shoot down a V1. No 3 Tempest Squadron, part of 150 Wing in Newchurch, Romney Marsh, were among the first to start to destroy the V1s; they shot down eight in the first day and went on to score more than 300 kills.

This was the first many people knew about the flying bomb campaign. Although the V1 engine noise was distinctive (“a hideous racket”, HE Bates described it), some eyewitnesses thought that the missiles were planes with their lights on, or aircraft on fire. They imagined that they were seeing enemy aircraft being shot down in flames, an encouraging prospect. Many of the missiles flew up the Thames Estuary and attempts were made to hit them as they rumbled overhead. The air raid warnings kept sounding, and some were still going off as people made their way to work in London on the Friday morning. In Hastings at West Hill, where St Clements Caves were used as an overnight shelter, people were concerned at the number of “aircraft” they could hear passing over. Normally they would have been told to move out at 09.00, but on this occasion, they were told to stay put. Many people began to feel a strange sense of foreboding. Later that morning, staff at the Ministry of Supply in London were sent to the basement for safety and remained there for much of the day. Clearly the arrival of the V1s could be concealed from the public no longer.

Jan Gore 3 June 2024.

References:

Diagram of the V1 flying bomb.

………………………………………………………………….

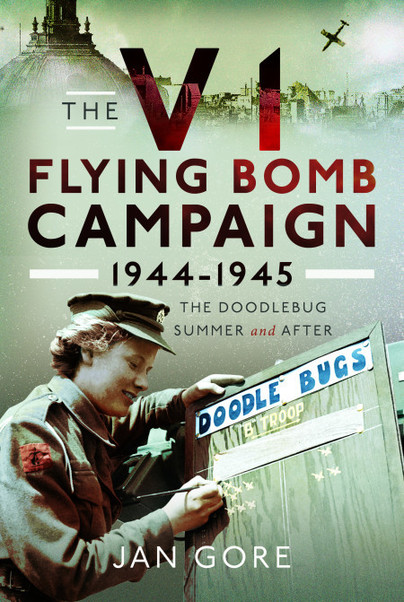

Recommended reading:

Order here.

Preorder here.