Author Guest Post: Dale DeBakcsy

Written in the Stars: The Legacy of Women in Astronomy and Space Exploration

When the ancient Greeks looked up to the night sky, they saw inscribed there a pantheon of mythical creatures, heroes, gods, and goddesses, all reflecting back at them the glories of their own civilization. Their celestial vault was a story written in starlight, one which we shall tell and retell long after those stars have drifted from their original homes, but it is not the only story to be found there. For some five hundred years now, women have trained their eyes and instruments on that same sky, and gifted us with some of our most profound insights into the history and evolution of our universe. Quite literally, wherever you turn your gaze, you will find some phenomenon that we now understand thanks to a figure whose road to astronomy was often strewn with obstacles, but whose passion to know and understand our place in the cosmos overcame all limitations.

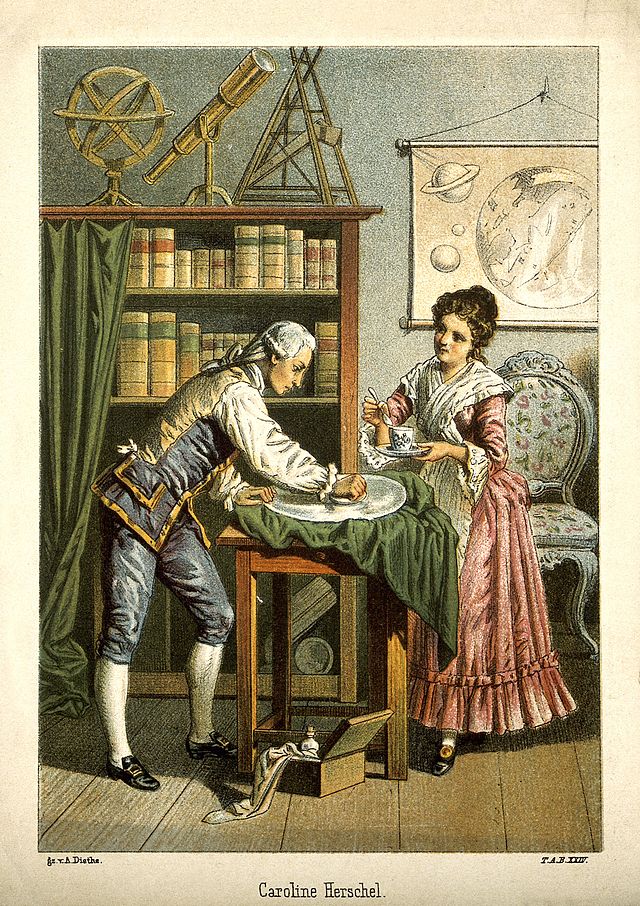

Let us take a stroll, then, through our universe, and get to know the women whose work allowed us to understand the mysteries we’ll find there. To begin with, we must find a star to observe, a task which since the 18th century was achievable thanks to the work of Caroline Herschel (1750-1848), who not only became a celebrity for her discovery of eight comets and some 2,500 nebulae, but who also corrected the accumulated errors in Europe’s most popular star charts, and produced, in 1798, her Catalogue of the Stars, which allowed astronomers in the centuries to come to quickly and accurately find the celestial objects they sought.

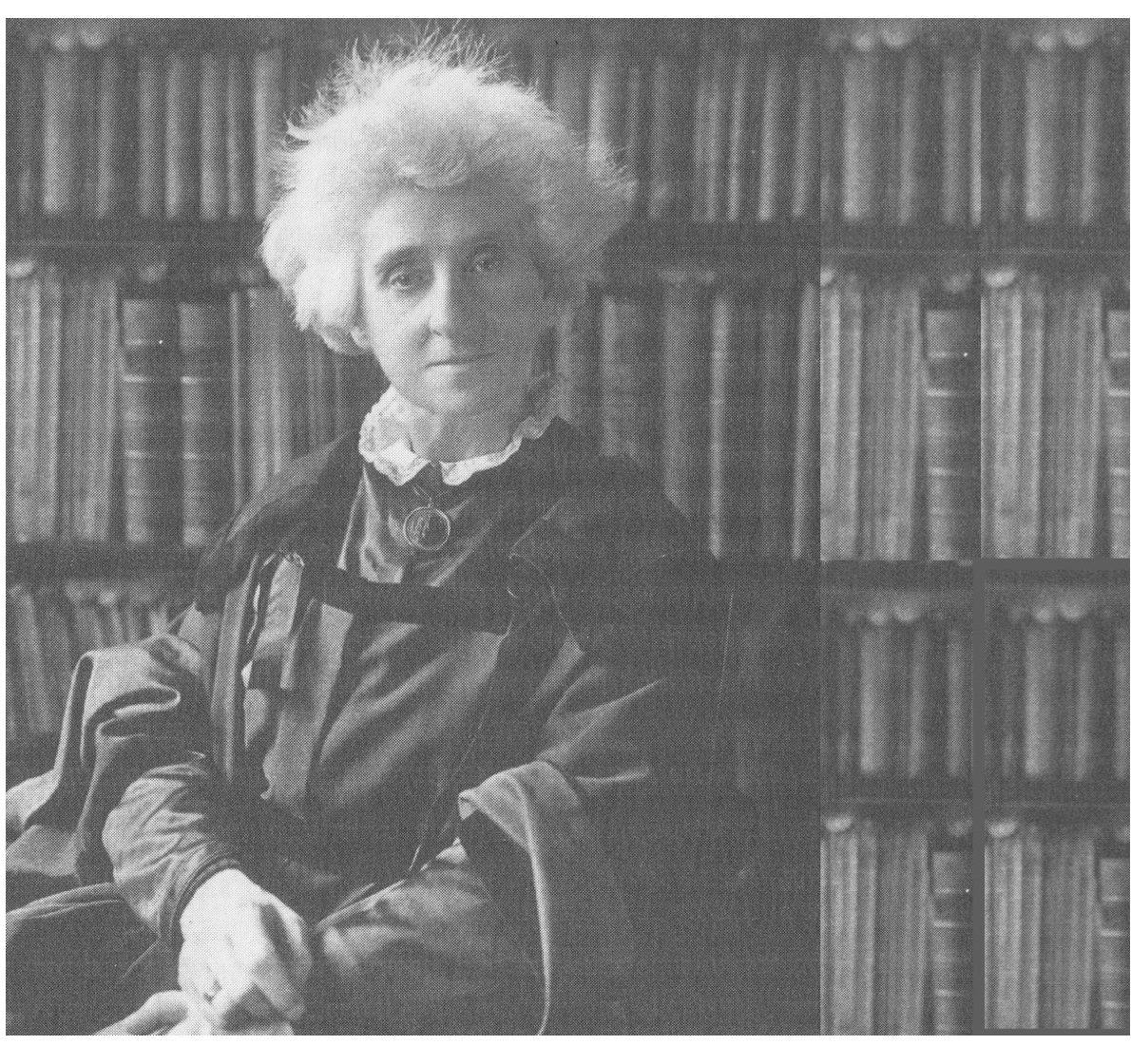

So we’ve found our star, now how do we learn about it? In the nineteenth century, astronomers struck upon the idea of spreading out the light of a star using a prism, and using the pattern of light they saw there (called a spectrum) to decode that star’s chemical makeup. To begin with, they had to rely on their drawings of the stellar spectra, a not ideal state of affairs that was resolved when Margaret Huggins (1848-1915) developed the procedures to allow spectra to be clearly photographed, permitting astronomers to create permanent and precise records of the contents of the stars they observed, an ability that gave rise to the great late 19th century push to completely record the spectra of the night sky.

This effort was centered at Harvard Observatory, where gathered a veritable Who’s Who of women astronomers, each of whom made fundamental contributions to our knowledge of the universe. To name just two who lit the way on our tour of the cosmos, Henrietta Swan Leavitt (1868-1921), through her studies of cepheid stars, gave us our first way of accurately measuring the distances between celestial objects, and thereby of having some sense of the size of our universe. Shortly thereafter, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin (1900-1979) solved a problem that had been plaguing astronomers since they first decoded the spectra of stars: now that we know what elements are in stars, how do we figure out how much of each element each star contains? Prior to Payne-Gaposchkin, it was assumed that stars have a composition similar to the planets they give rise to, but her research discovered that, in fact, hydrogen rules the universe, making up some 90% of stellar content in spite of the fact that it makes up only some 11% of our oceans and less than 1% of our crust.

Expanding our scope from that of the individual stars which pioneering women astronomers taught us to find, photograph, interpret, and map, we come to the galaxies, each made of some 100 billion stars, and ask the question, how did these galaxies come to be, how do they move, and what is their ultimate fate? Here again, women researchers have led the way, with figures like Beatrice Tinsley (1941-1981), who in her short life revolutionized our standard pictures of stable and reliable galaxies by painting a dynamic picture of their shifting content over time, Vera Rubin (1928-2016), whose measurement of unexpectedly high stellar velocities around galactic centers sparked a debate about the possible existence of dark matter that rages still, and Margaret Burbridge (1919-2020), who provided an explanation for the shifting content of galaxies by her foundational elucidation of how different processes within the interiors of suns give rise to different elements.

We’ve taken quite a trip – let’s come back home for a while to our own solar system, which has puzzles aplenty of its own. There is our own sun, which we know better thanks to the longest running set of single instrument observations of it, carried out by Hisako Koyama (1916-1997), as well as our neighbors the planets, the laser-mapping of which was directed by Maria Zuber, and the robotic exploration of which has been guided by Megan Lin, with the discovery of objects on beyond Pluto being the result of the never give up, never surrender mentality of Jane Luu.

Finally we come to rest here, back on Earth, where three generations of women have not only observed the night sky, but have taken the first steps into it, from the pioneering parachutist turned cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, to the physicist-athlete phenomenon Sally Ride, to the engineer’s engineer Kathryn Sullivan, to the record-smashing Peggy Whitson. Their road to space was not an easy one, and is paved with as much frustration, betrayal, and tragedy as triumph, but the march is on, and hopefully the day is not long in coming when a woman, casually strolling the sands of Mars, will come across a small plaque to Jerrie Cobb, or Jane Hart, or any of the other dozens of women who never got their chance to slip the bonds of Earth, but whose efforts made it possible for generations of women to come to take their place in the night sky next to Orion and Hercules, as the great heroes of our own time, forged in adversity, and radiant in achievement.

A History of Women in Astronomy and Space Exploration is available to preorder here.