Author Guest Post: Barbara Walsh

Armistice Day 2023:

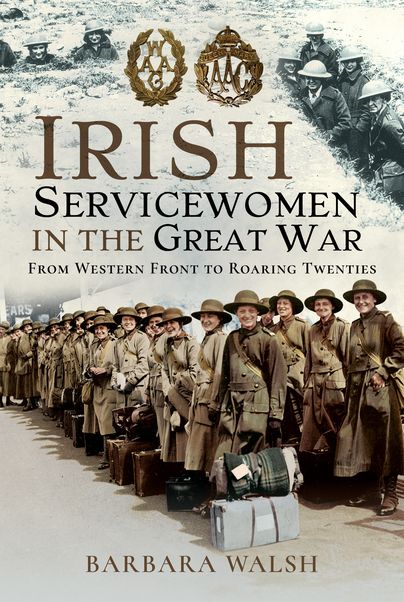

The story behind Barbara Walsh’s book about Army women in the Great War

Readers of my book, Irish Servicewomen in the Great War (P & S 2020) are not likely to have realised that some of the vivid accounts of events in this study were initially based on the true life experiences of several of my family relatives who had served in France in the first world war. These were all off-repeated stories that I had grown up with as a child and had become well-remembered tales. Of course, when writing the book, all these personal reminiscences had to be checked by rigorous academic research to ensure that any details of their army days that I already knew about had been strictly accurate. Facts, figures and information all had to be confirmed from official records.

Like many other veterans of that conflict, that generation had later tried forget the traumas and horrors of those days and rarely later spoke in great detail of the real dangers that they and their army friends had experienced. For the most part they seemed only to have wanted to recall some of the happier moments and the wonderful friends and companionship that army life had thrust upon them.

When putting the book together I had to also bear in mind, of course, that the personal photographs that I was given access to as an illustrations of army service days were all taken in the months following the signing of the Armistice. The use of privately-owned cameras was strictly forbidden during wartime. It was nonetheless very satisfying for me to discover that my rigorous research of accounts supplied from other sources were able to fully confirm the accuracy of any of these first-hand stories and faded snapshots that I had been able to make use of.

In regard to the need for a book to provide a focus on Irishwomen – can I add that it has been often overlooked that they were as eager as their English colleagues to enroll in the WAAC (Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps) just as soon as the War Office issued the call for female help in early Spring ,1917. It had been a wise decision. The input of these army servicewomen’s work brought about huge changes which had an immediate and direct effect on the course of the First World War. .

As described in the book, the enrolment of recruits was followed by about two weeks training before they were put to work to replace men in a variety of tasks such as office workers, transport drivers, army cooks and catering staff. It should also not be forgotten that a small number of these army women also performed far more serious key roles behind the scenes in France. For example, when former Post Office girls from many of the Irish Exchanges were seconded to the Royal Engineers in France, they were the foremost operators of the high-tech Signal Units that became the core of the Army Lines of Communication. This was the era that introduced telegraph and telephone links that could link the Front Line to and Bases behind the lines. Also, behind the scenes – but never officially spoken of until many years’ later for security reasons – were other young women who participated in top-secret cryptanalyst and code-breaking tasks behind the lines..

It is a great pity that so many of the records for the higher ranking members of these army women did not survive the bombing raids on London in the second world war. The volunteers were drawn from every strata of society and Irish girls from working-class or farming backgrounds, Protestant and Catholic alike, were as much in evidence in army bases as were the daughters of well-heeled middle-class and gentrified Anglo-Irish families from Dublin, Cork and Belfast.

As described in the book, the WAAC (later QMAAC) Irish Command HQ was based in Dublin. They supplied key support for several city Barracks, the Officers’ Training Corps in Trinity College and elsewhere. For example, a contingent of WAACs were soon based in the army towns of Newbridge, Fermoy, Tipperary and Ballyshannon and they also played an important role in the army protection of Cork harbour. By the end of the war these army servicewomen had a presence in almost every other army camp and Barracks throughout Ireland.

The demobilisation of troops had commenced in late 1918. A momentous task had lain ahead for all who were involved in the movement and repatriation of men and army equipment from France and elsewhere back to the mainland. Across the whole of the United Kingdom barracks and camps were being returned to their pre-war status and the women who undertook all checking and paperwork that was involved became even more indispensable as a result.

Pen and Sword’s Irish Servicewomen in the Great War also includes an investigation of what turned out to be the extremely useful contribution made by these army women’s essential back-up support for the winding-down of army’s needs following the conflict of the First War. This unheralded input lasted until 1921 but it been a topic that had often been sadly sidelined by historians. Moreover, it cannot be overlooked that the accounts provided in the book to include an outline of the ensuing exodus of former servicemen and women to settle in overseas colonies or elsewhere, also carried an importance essential to any investigation of the impact of World War I.

Now over a hundred years later it is still good to stop and reflect for a moment that the people who designed the 1918 Armistice had hoped the experience of that conflict’s horrors and suffering would ensure that those four years would remain forever known across the whole wide world. as the ‘The war to end all wars’. War on this scale must not ever happen again.

It was an aspiration sadly never achieved.

Order your copy here.