Author Guest Post: Anthony Payne

“HE WAS A MONSTER AND I WAS ONE OF HIS VICTIMS” – THE STORY OF A FATAL CHARMER.

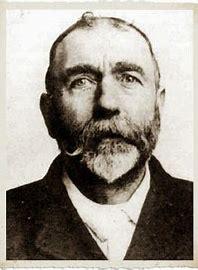

The Moat Farm Murder was carried out in 1899 but was not properly investigated until four years later. It proved to be one of the criminal sensations of its day. The perpetrator, Samuel Herbert Dougal, had been a serving soldier in the Royal Engineers and had risen to the rank of Quartermaster-Sergeant. He had been involved in Ordnance Survey work in Wales, and in the modernisation and photographic recording of the large fort (The Citadel) at Halifax, Nova Scotia. In Canada, his first two wives had both died of sudden, acute and violent symptoms, though their deaths were officially recorded as tuberculosis.

After leaving the army, Dougal went from job to job, narrowly avoiding convictions for arson (to claim the insurance, he twice tried to burn down the Royston Crow pub of which he was the landlord) and for theft (an ill- fated case brought by one of his female victims who he had treated abominably). He was finally jailed for forging the signature of the Commanding Officer of Forces in Dublin on a cheque for £35. Although he was sentenced to a year’s hard labour at Pentonville, he was declared insane on the basis of a laughably faked attempt at suicide, and served out his time in the far more congenial surroundings of a lunatic asylum is Surrey.

Dougal met his most notable victim – Miss Camille Cecile Holland – at the Earl’s Court Exhibition in the autumn of 1898. She was an independent woman of 56 with considerable investments, but Dougal had no difficulty in sweeping her off her feet and they moved into lodgings near Brighton. Shortly afterwards he persuaded her to purchase Coldhams Farm at Clavering, Essex. This was a house so isolated that it had once been the lair of a highwayman; the nearest cottage was half a mile away. Dougal was to become a “gentleman farmer” and the farm (which they re-named “The Moat Farm” on account of the various channels which surrounded it) would be their love-nest. However, shortly after moving in Miss Holland disappeared, with Dougal insisting that she had gone travelling on a whim, and even suggesting that she had been in correspondence with an old flame in the form of a mariner (he had actually drowned at sea many decades ago).

Dougal was now in possession of a farm with a value of £1500, and proceeded to empty Miss Holland’s bank account, to put the farm in his own name, and to sell her investments, all by means of forged letters. His skill at draughtsmanship had been honed in the army where he was nicknamed “Jim the Penman” and provided a basis for his crimes.

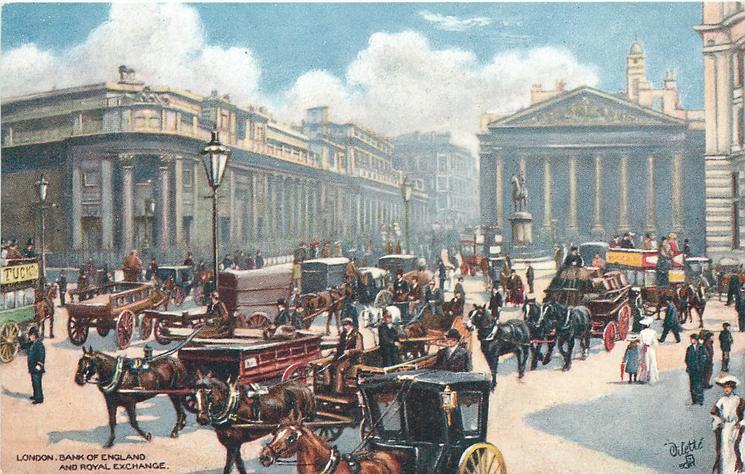

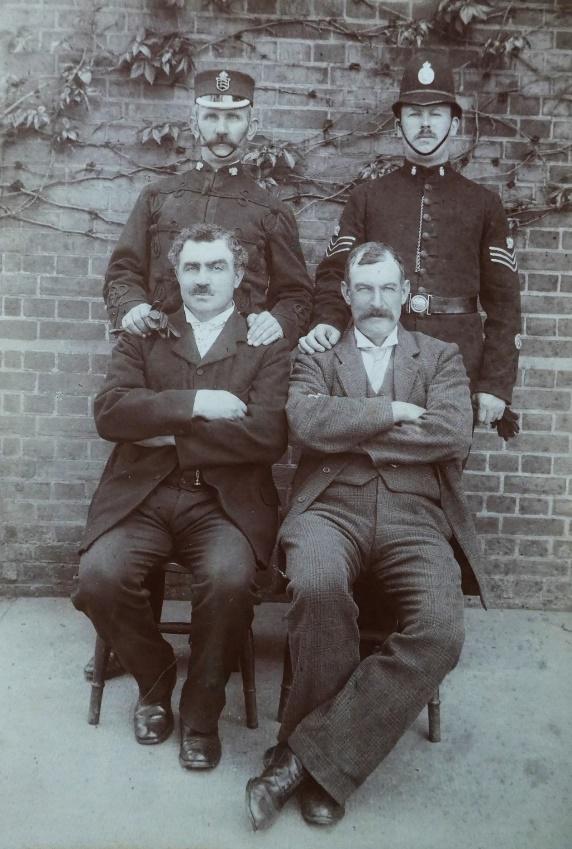

The authorities became increasingly concerned about Dougal’s financial affairs but were curiously unconcerned about the disappearance of Miss Holland; even her nearest relatives (two nephews and a niece) and financial advisers failed to pursue her whereabouts. Having acquired all her money, Dougal decided to flee the country but made the mistake of visiting the Bank of England to change high denomination notes into sovereigns. Many of the banknotes were on the police “stop list” and he was arrested (but not before an escape attempt which ended in a cul-de-sac) and taken to the City of London Police HQ at Old Jewry and, on the following day, to await trial for fraud.

The local police actually took over The Moat Farm, living in it for several weeks and searching for evidence to support the case for fraud, forgery and embezzlement which was being assembled against Dougal. Meanwhile, the public became increasingly convinced that Dougal had done away with Miss Holland. Letters (often anonymous) urged the police to greater efforts; false letters of confession (often signed) were also received. Writers who claimed unusual powers (such as seeing emotional colours) endeavoured to assist the police in discovering a body. The police responded by draining, dragging and probing the moats and water channels surrounding the farmhouse, all to no avail. A workforce was now employed to dig over the grounds of the farmhouse. All this time, the trial for fraud and forgery was proceeding; the prosecution was doing badly as their star witness suddenly and unexpectedly did a volte-face in court, insisting that the signatures of “Miss Holland” (actually penned by Dougal) were genuine. Dougal seemed likely to be acquitted, but at the crucial moment a farm labourer recalled a drainage ditch which had been filled in just after Dougal and Miss Holland took over the farm. In a recess in the wall of the ditch, her corpse was discovered with a bullet in the skull. People travelled hundreds of miles to trample over the grounds, take photographs and abscond with souvenirs.

Following the inquest, the trial for fraud morphed into one for murder. Identification lay at the heart of the case. In life, Miss Holland had extraordinarily small feet (size 2½) of which she was extremely proud. Her bootmaker was able to identify his trademark on the boots worn by the corpse. As the judge remarked, if the boots were those of Miss Holland, it must be supposed that the corpse was hers also. He also reminded the jury that they must always question the motive for a murder – who would benefit? In this case it was Dougal who gained a valuable farm and several thousand pounds.

Dougal was found guilty. His life of rural ease (accompanied by numerous sexual conquests including three sisters from the same family) was now well and truly at an end. From jail he wrote letters to the Home Secretary pleading for mercy, and to The Sun newspaper explaining that the death of Miss Holland was an unfortunate accident when a gun he was holding went off unexpectedly. His writings fell on stony ground. At his execution, the prison Chaplain asked if he were guilty or not guilty? His last word was “guilty”.

In succeeding years, the case was sufficiently famous that Dougal has been portrayed on radio both by Charles Laughton and Orson Welles but is little remembered today. It should be.

…………………………………………………………

Order your copy here.