World-Changing Women

Guest post from Paul Chrystal.

The common perception of the socio-political role of women active in the great civilisations of Greece and Rome is that they were suppressed, subservient, secluded, and excluded. To a large degree that is correct, but it does call in to question how great can a cradle of civilization be when it ostracizes a good 50 per cent of its citizens. We have all heard of the obvious notable exceptions to the routine historical gagging: Sappho, Lucretia, Verginia, Lesbia, the Agrippinas and the foreign women who did their utmost to break the Graeco-Roman mould and disrupt the world order: Cleopatra VII, Boudicca, Teuta and Zenobia, for example.

But there were many more of these outstanding women who gave powerful Greek and Roman men pause for thought and caused them great anxiety and insecurity. Over 150 of them are described and celebrated in my recently published World-Changing Women: 150 women who rewrote the histories of…

Here are three of them:

Pheretima, ca 500 bce, brilliant commander eaten by worms

A cautionary tale involved Pheretima (d. 515 bce), wife of the Greek CyrenaeanKing Battus III the Lame and the last queen of the Battiad dynasty in Cyrenaica (present day northern Libya). Herodotus tells us that when Battus, (the grandfather of Pheretima’s son Arcesilaus), died in 530 bce, Arcesilaus III became king but was defeated in a civil war after 518 bce and exiled to Samos while Pheretima went to the court of King Evelthon in Salamis, Cyprus. Evelthon showered Pheretima with gifts, but would not give her an army, arguing that such a command was simply not right for a woman.

Neither Pheretima nor Arcesilaus, however, took this lying down: he recruited an army in Samos, returned with it to Cyrenaica, and regained his position by murdering and exiling his political opponents – urged on no doubt by Pheretima.

When Arcesilaus left Cyrene for Barca, Pheretima ruled the city but Arcesilaus was murdered by exiled Cyrenaeans intent on revenge. Pheretima went hot-foot to Arysandes, the Persian governor of Egypt, to enlist help in avenging the death of her son; Arysandes loaned her Egypt’s army and navy. She marched to Barca and demanded the surrender of those Barcaeans responsiblefor the murder of Arcesilaus; when the Barcaeans refused insisting that they were all complicit, Pheretima laid siege to Barca for nine months. Amasis, her Persian commander, played a trick on the Barcaeans in which he ordered his soldiers to dig a large trench in front of the city camouflaged with wooden planks and earth; he then lured the Barcaeans out of the city with a promise of a well-rewarded armistice. They literally fell into the trap: Pheretima ordered the Barcaean wives’ breasts be cut off and nailed on the city walls, and enslaved the rest of the Barcaeans to the Persians.

So Pheretima avenged her son, returned to Egypt, and returned the army and navy to the governor. However, while in Egypt, Pheretima contracted a contagious parasitic skin disease, and died in late 515 bce. Herodotus tells us that she was eaten alive by worms – punishment by the gods for her butchery of the of the women of Barca? She lives on in the name of the worm which infested her – Pheretima is a genus of earthworms found mostly in New Guinea and parts of Southeast Asia.

Teuta – queen and resolute pirate

Teuta was a pirate of some audacity and determination. She was the queen regent of the Ardiaei tribe in Illyria; she reigned from about 231 bce to 227 bce when she succeeded her alcoholic husband Agron acting as regent for her young stepson Pinnes. Teuta avidly backed the piratical raids carried out by her subjects against neighbouring states.

Things began to escalate when Teuta captured and later fortified Dyrrachium and Phoenice; while off the coast of Onchesmos, her ships raided a flotilla of Roman merchant vessels. After this Teuta’s forces extended their piratical operations further southward into the Ionian Sea, defeating the combined

Achaean and Aetolian fleet in the battle of Paxos and capturing the island of Corcyra. This enabled Teuta to attack the crucial trade routes between mainland Greece and the Greek cities in Magna Graecia. Teuta was now the ‘terror of the Adriatic Sea’.

In 230 bce the Romans protested to Teuta but she glibly told the ambassadors that according to Ilyrian law, piracy was a legal trade and that Rome had no right to interfere in what was effectively private enterprise and that ‘it was never the custom of royalty to prevent any advantage its subjects could get from the sea’.

Teuta then imprudently sanctioned the murder of one of the Roman envoys, Coruncanius, and imprisoned the other. The Romans reacted on a massive scale when they mobilised and set sail with an army of 20,000 troops, 200 cavalry, and the entire Roman fleet of 200 ships. They laid siege to Scodra, Teuta’s capital city. She surrendered ignominiously in 227 ending her life in grief by throwing herself from the Orjen mountains at Lipci in modern Montenegro.

Julia Balbilla – royal correspondent to Hadrian

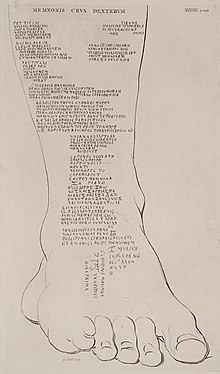

Around 130 ce Julia Balbilla accompanied Hadrian and the Empress Vibia Sabina on tours of the Nile valley, as court poetess and as a kind of royal correspondent. To record their visit she inscribed four epigrams in ancient Aeolic dialect – as used by Sappho some 800 years earlier – on the left leg and foot of one of the Colossi of Memnon in Thebes (a monumental statue of the pharaoh Amenophis III).

In so doing, Julia was following a time-honoured tradition celebrating Memnon’s amazing early morning ‘singing’ – an audible phenomenon emanating from fractures to the statue made by an earthquake.

Her first three epigrams dutifully commemorate the royal visit; the fourth Julia’s personal experience. Julia’s erudition is clearly evident from these inscriptions: she is not only familiar with a long-obsolete ancient Greek dialect and metre, but she displays a working knowledge of relevant Egyptian and Greek mythology. Empress Vibia Sabina added an inscription of her own on the instep of the left foot.

Paul Chrystal

Order your copy here.