Women’s History Month – Stephen M Cullen

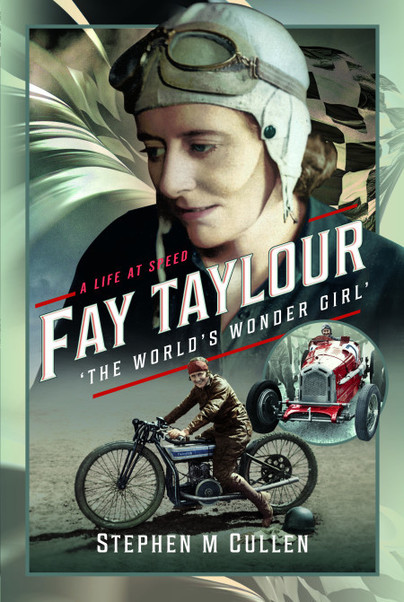

Fay Taylour, A Life at Speed.

‘The World’s Wonder Girl’, ‘Flying Fay Taylour’, ‘Queen of the Dirt Track’, ‘Fastest Woman on Wheels’ – these were some of the sobriquets bestowed on Fay Taylour by the press. Yet forty years after her death, few have heard of Fay Taylour, the most successful woman motorsports competitor ever. In the 1920s, she was one of a very small group of women who raced against men in the new and dangerous sport of speedway. Eventually, and in large part due to Taylour’s successes against the best male competitors, women were banned from competing against men in the UK. Undeterred, she made an even bigger name for herself racing against men in the home of speedway, Australia. She then turned her hand to long-distance car racing, and the emergent sport of midget motor car speedway. She raced around the world, including in Germany where she became sympathetic to the new Nazi regime. That sympathy would turn to strong support and lead to three years of detention by the British government during the Second World War. Her pro-Nazi politics, and the suspension of motorsports during the war, fractured her career. Yet, against all the odds, she rebuilt her career racing in the USA before being banned from the country for years, a ban that returned her to Australia and New Zealand for more fame won by beating their best men on the midget car track. By the time she retired, she had been on the track for forty years, a difficult, dangerous, obstinate, and determined pioneer woman racer.

Fay Taylour was born in Birr, County Offaly, Ireland in 1904, one of three daughters of a senior officer in the Royal Irish Constabulary. The women in her family included a pioneering doctor, a Suffragette, and a teacher at the famous Dublin girls’ school, Alexandra College, which Taylour attended at the height of the Anglo-Irish War. The British defeat in that war saw her family re-locate to England, where Taylour discovered motor bikes were an antidote to the boredom of polite middle-class society. In just over a year she won a succession of trophies, attracting the attention of the Coventry-based AJS, and Rudge Whitworth companies. She became a works rider, trialling their bikes in endurance racing. But what she really wanted was speed. This passion for speed took her to the new sport of speedway. After seeing an early speedway race at Stamford Bridge, Fulham, she determined to break into the sport. Not for the last time, it looked as if male promoters would prevent her even getting onto the track. But helped by a male racer, Lionel Wills, she smuggled herself into a practice session at the new Crystal Palace track. Hiding her long auburn hair under her helmet, she sped around the track, to the anger of the promoter when he discovered her sex. But that anger turned to acceptance, and Taylour’s speedway career had started.

Speedway was a major spectator sport in the late 1920s and 1930s, highly popular with its largely working class audience. The first British event at Epping Forest in 1928 saw upwards of 30,000 spectators, and in a year there were 60 tracks. It was a dangerous sport, a professional sport with flamboyant champions like ‘Sprouts’ Elder, the great American rider, and ‘Super’ Sig Schlam and Ron Johnson, the Australian stars. Women were banned from the speedway leagues but could race in non-league races. Taylour was one of a handful of women who took the male giants of the track on at the game. Her first race was at Crystal Palace in June 1928, when she became the first woman to compete in British speedway. She quickly mastered the essential technique of ‘broadsiding’ which enabled corners to be taken at full throttle on bikes with no brakes. Within weeks, she was winning races against the best, and at the end of the 1928 season, the new ‘Broadside Queen’ took her bikes and her skills to the home of speedway, Australia. In two tours of Australia and New Zealand she astounded the antipodean public with victory after victory. Her success saw her beat ‘Super’ Sig Schlam on his home ground, Claremont Speedway, Perth. As the press put it, ‘her riding can only be described as brilliant’. She left Australia in June 1930, to return to Britain for what she thought would be a season of total dominance on the British tracks. But it was not to be. While Taylour was still at sea, the sports UK governing body banned women from speedway.

Angered, but not deterred, Taylour turned to motor car racing. She competed at Brooklands, where she established the fastest lap time on the hill circuit and won the 1931 Ladies Handicap. Despite these successes, it was difficult for Taylour to establish herself, as motor racing necessitated access to far more funds than needed for speedway. She moved on again, racing in the Monte Carlo Rallye, the Round Italy Race, and took part in hill-climbs and the new sport of midget car racing. However, the expulsion of women from speedway had its effect, and the later 1930s brought problems, both sporting and personal. It was at this point she abandoned her long-held views about sex, and started a love life that matched her sporting life. Intense as her love life became, she was clear that what she wanted was the thrills and demands of motorsports. As the war clouds grew, she took a high-powered car to South Africa, and competed in the fifth South African Grand Prix. Afterwards, still in search of sponsors and cars, she travelled to Germany, where motorsports were enthusiastically promoted by the Nazi regime. Taylour then returned to Britain, just a week before the outbreak of war.

Back in London, she began to talk frequently about the need to oppose the war. Her outspokenness led to a visit by Special Branch, who warned her against her activity. This was the worst thing that could have been said to her, as she always took a ‘no’ as a challenge. She immediately joined Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirt movement, which was running an anti-war campaign. Worse, she became involved with other women in pro-Hitler groups. When detention without trial was introduced in the spring of 1940, it was inevitable that Taylour would be detained. She was held for three years, first in Holloway Gaol then on the Isle of Man. There she was described by the camp governor as, ‘one of the worst pro-Nazi’ prisoners. She was released in October 1943, and went to live in Dublin in neutral Éire.

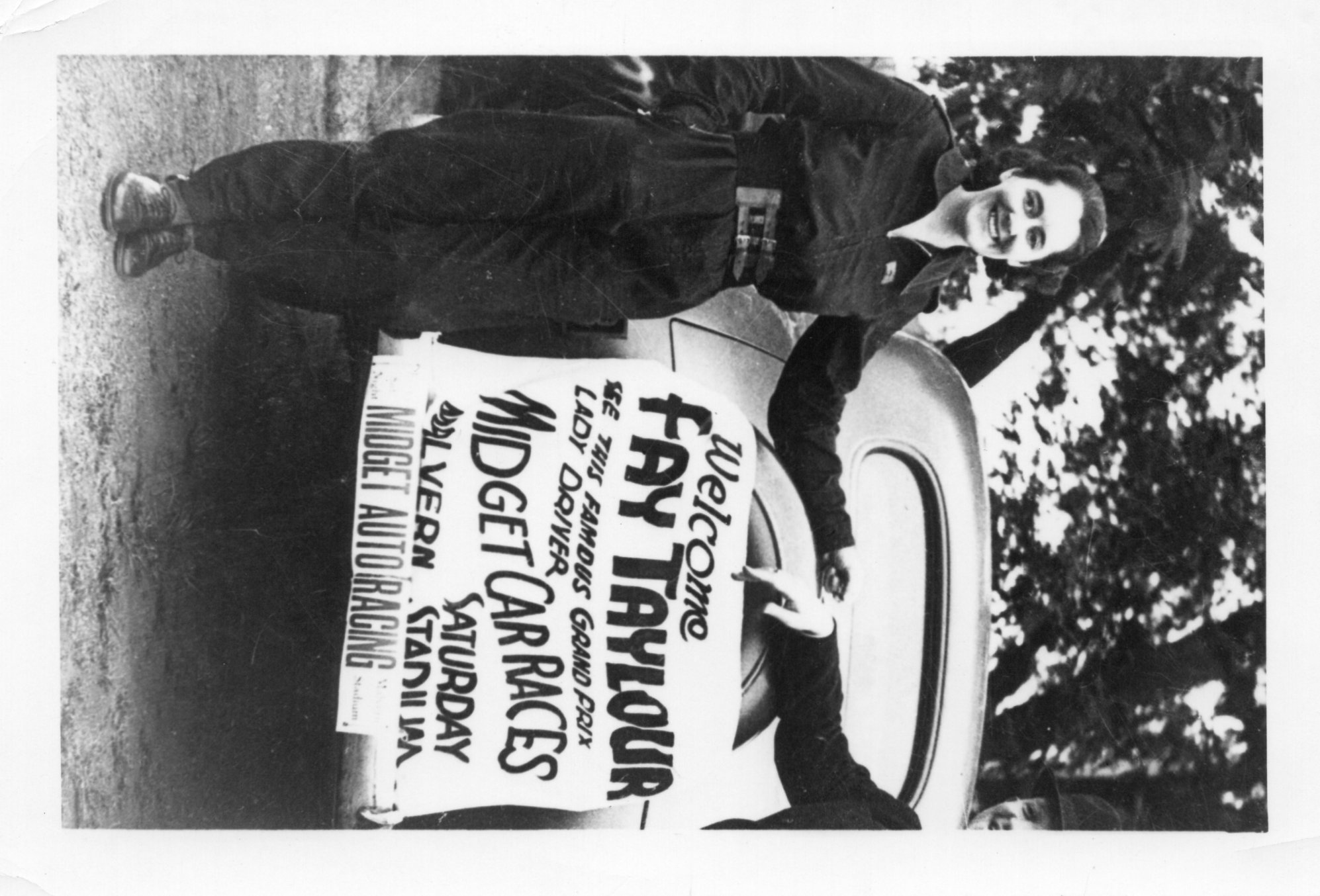

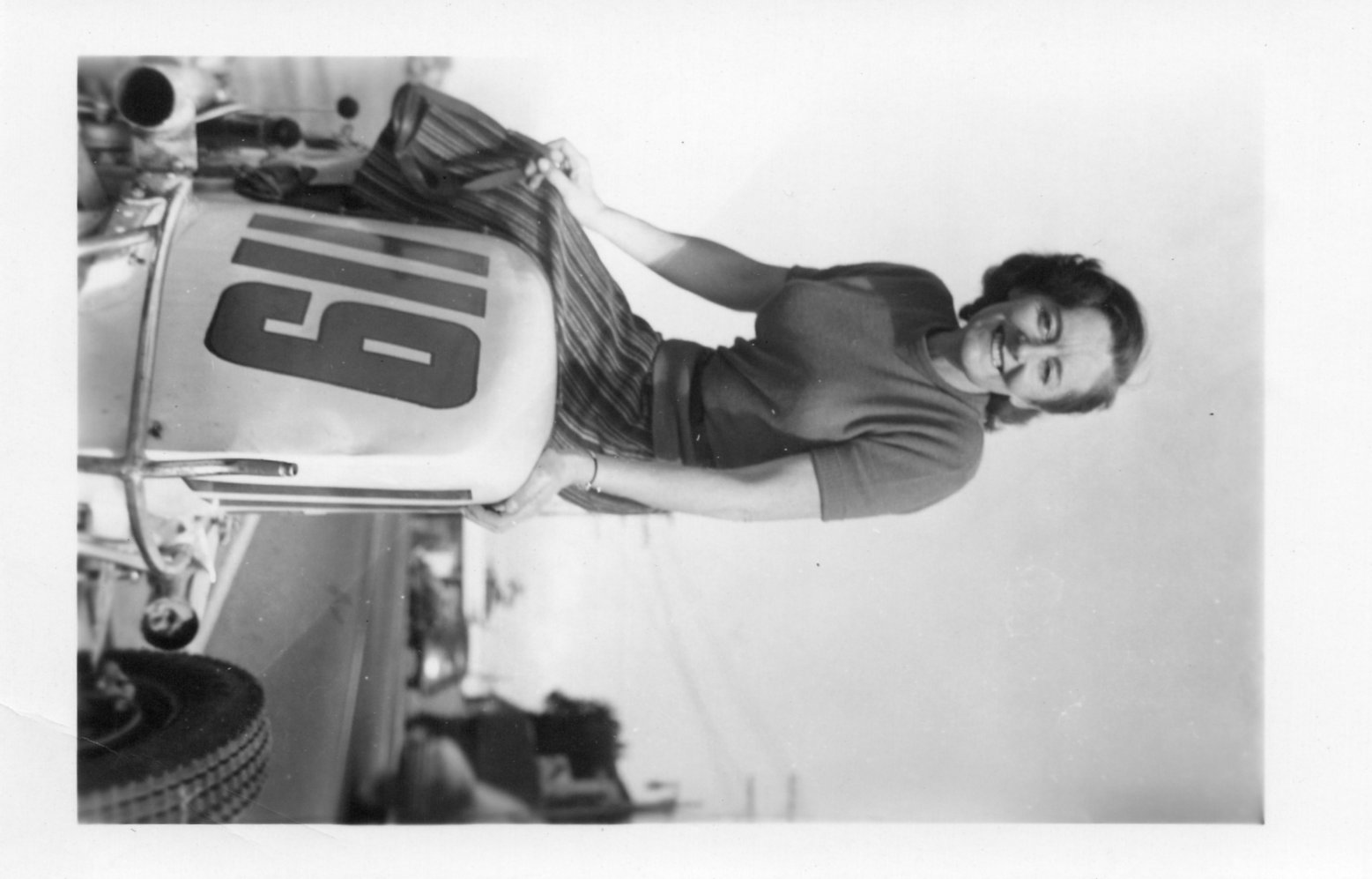

Taylour spent six years in Dublin, taking odd jobs, occasionally racing in England once the war finished, enjoying a very active love life, but all the while dreaming of a revitalised sporting career. Finally, armed with a new Irish passport, she moved to Hollywood to sell British sports cars in a dealership on Sunset Boulevard. One of her first customers was Clark Gable, to whom she sold a Jaguar XK 120, the fastest sports car of its day. But that was just an interlude and frustrated by the governing body of the American Automobile Association, who ‘refused to recognise women’ on the race track, she turned once more to midget car racing. She raced across America and found new fame on the track and off, including on popular television programmes like ‘What’s My Line’. It looked as if she had, once again, surmounted the obstacles that men, and herself, had put in the way of her career. But it was not to be.

In 1952 she returned to England to see her ailing father. After his death, she hastened to return to the American midget car world, only to find that US and British intelligence had been exchanging information on her political past. The result was that she had her visa withdrawn and was banned from re-entering the USA. This was a stunning blow to Taylour, who was now nearly 40. Recovering, she decided to appeal the ban, and return to her old racing grounds in Australia and New Zealand, this time in midget cars. She spent the next three years racing there, once again making headlines, beating the best male drivers. Her skills were such that, at one point, male drivers tried to have her banned from the track. Finally, in the summer of 1955 she regained her visa for the USA.

That year would prove to be Taylour’s sporting swansong. She raced across the USA once more, this time in the hectic world of State Fairs’ midget car races. It was exhausting, and frustrating, and by the time she took part in her final race, on 28th October 1955, she knew that, aged 51, her life at speed was over. It took her a few years to readjust, and at one time she came very near to suicide. She had a difficult, wandering life in America, akin to a real life road movie. Eventually she found some stability working at a womens’ college in Massachusetts. This was followed by long sea cruises, and eventually she came to rest in Dorset, where she died in 1983.

Fay Taylour’s life was remarkable. She remains the most successful woman motorsports’ competitor yet. Her dream of hundreds of women taking part in motorsports seems even further away than when she made the comment in Australia in the early 1930s. In her personal life she was as determined to act as she wished, just as she did on the track. In her political life, she was seen by the British government as dangerous and wrong. Her wartime politics were unpalatable. She never recanted, and in the post-war period added an eclectic mix of other causes to her politics, including support for Castro, the IRA, North Vietnam, and John F. Kennedy. Fay Taylour – a trail blazer, a complex woman, and a fitting addition to Women’s History Month.

Order your copy of Fay Taylour is available to order here.