Women’s History Month – Sally Waller

Dorothea Beale –Pioneering Women’s Education

Dorothea Beale was born into an upper middle class family in 1831, at a time when little was expected from girls of such rank. The acquisition of a smattering of ‘accomplishments’, was all that was deemed necessary for young ladies to make a successful marriage and fulfil their place in society. Such girls spent their youth dependent on their fathers, and their adult years dependent on their husbands. Their energies were absorbed by child-bearing and the supervision of their households, with perhaps some charitable work alongside. Strangely enough, as Dorothea was later to report, middle-class girls were often more ignorant than their working class counterparts.

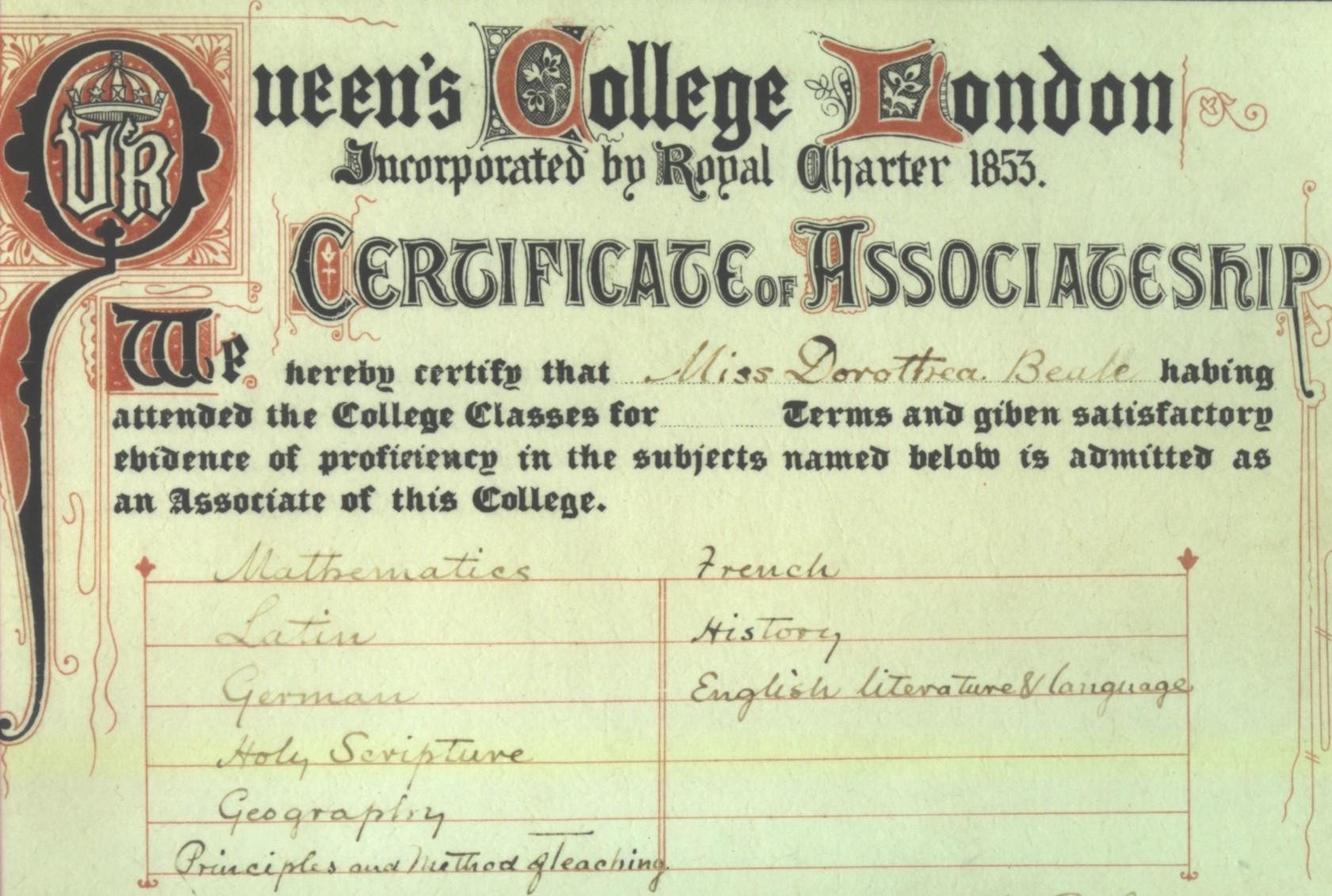

Dorothea, however, defied such norms. She was extremely fortunate that her own enlightened parents had rather different expectations of their daughters. She was encouraged to study and and pursue her own interests; she was never pushed into marriage. She became one of the first students to study at the pioneering all-women’s ‘Queen’s College’ in London, achieving much distinction. This lead her to embark on a career in teaching. There was nothing revolutionary about that, but there was much that was innovative and unconventional about Dorothea’s approach to education, and particularly to the education of girls. She was determined that women should have every opportunity to develop their talents and believed that this would only come about if girls were encouraged to think for themselves and learn from their own mistakes, with the maximum of support and minimum of ‘rules’. Whilst this might not be a controversial educational premise in the 21st century, it certainly was in the mid-nineteenth, as she was to discover in her early teaching posts at Queen’s and Casterton, Westmorland.

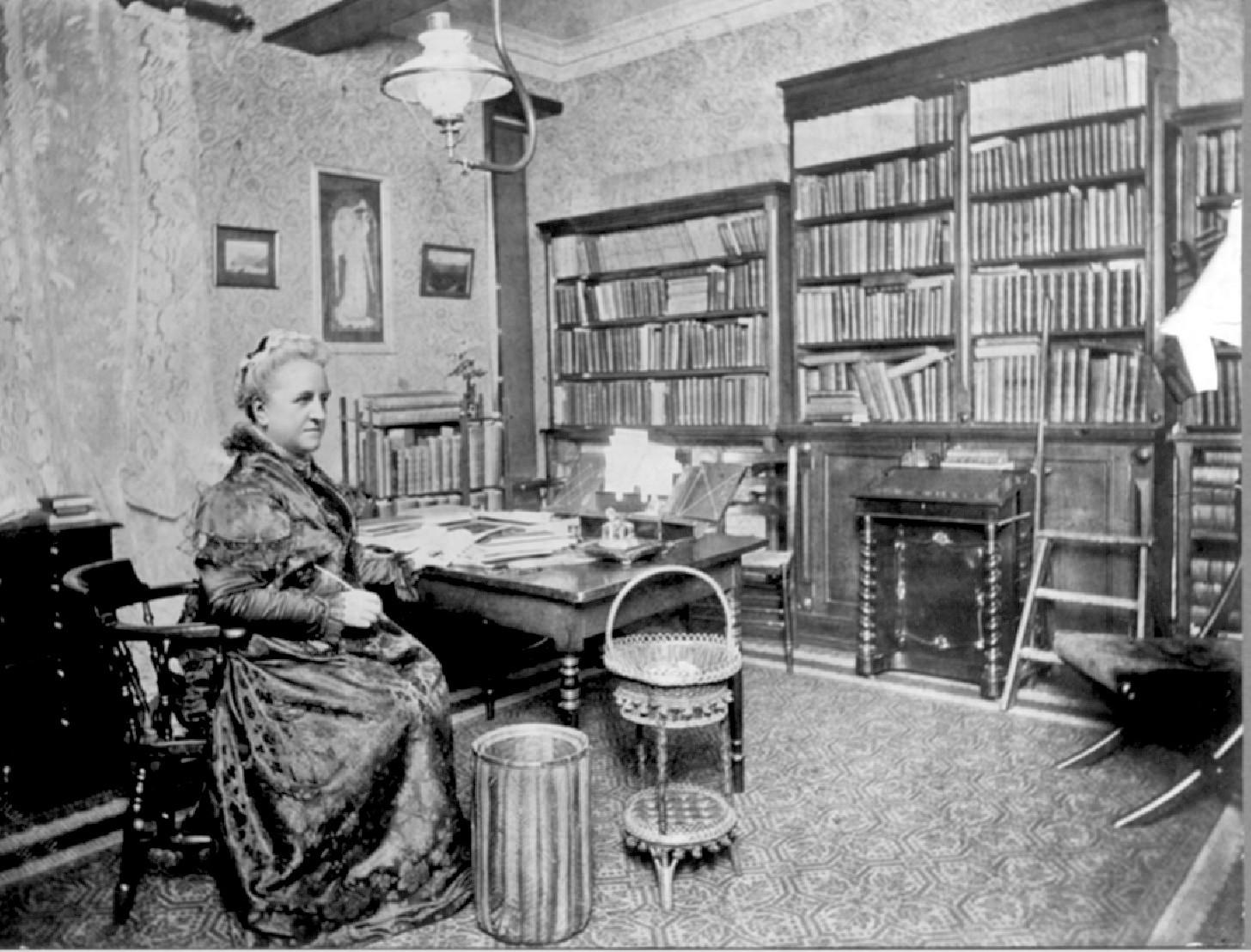

Dorothea had high hopes when she became Principal of the relatively new ‘Cheltenham Ladies’ College’, at just 27 years old, in 1858. However, she took on a College in dire financial difficulties, and one struggling to combat local prejudice that accused it of trying to ‘turn girls into boys’. Addressing such hostility and trying to persuade the all-male Ladies’ College Council to accept her educational views roused all Dorothea’s fighting instincts. Stubborn and convinced that she was correct, Dorothea won all her battles through a mixture of determination, persuasion and patience. She thus developed a school that was virtually unique in offering girls a curriculum that included Mathematics and Science, as well as providing its own certificated examinations under the auspices of visiting university professors.

Dorothea’s personal standing was much enhanced when she was invited to provide evidence to the Schools’ Inquiry Commission (1864-8). This government-appointed body had reluctantly agreed to report on the state of girls’ schools as well as boys’ and whilst it found much to condemn in most girls’ establishments, it praised the Ladies’ College as a beacon of excellence. Aware of the advantages that would accrue from putting together, editing and publishing the results of this Inquiry with respect to the girls’ schools, Dorothea spent many hours selecting material and writing a preface to what became a ground-breaking publication. This propelled her onto the national and international educational stage and led to many speaking engagements and the publication of a variety of pamphlets, which helped to promote her educational philosophy and reached a wide audience.

As a respected authority on education, Dorothea was party to the debates and trials which led to the opening up of public examinations to women. She was among the first Principals not only to enter girls for ‘local’ examinations –the equivalent of GCSE and A levels today – but also to educate them to degree level, taking advantage of London University’s early scheme to allow young women to sit examinations at the Ladies’ College. In time, girls left the College to enter the new women’s colleges being developed at the traditional universities, but throughout her time in Cheltenham, Dorothea’s Ladies’ College had a thriving higher education sector, for which new premises were built and where many new teachers were trained. As Dorothea sent increasing numbers of women out into the world with the intention of pursuing a career, she thus helped to create a new ideal of the middle class woman.

Dorothea did not neglect early years’ teaching either. She was one of the first to set up a kindergarten following the principles of Froebel who, like her, believed in the importance of learning and character-development through play. She trained potential kindergarten specialists for this novel field of learning, employing methods adopted from Montessori and Pestalozzi. She was also a keen supporter of the Parents’ National Education Union and firmly believed that an individual’s mental capacities only became fully and properly developed through lifelong education, from the earliest years at home to adulthood. For former students she created a College Guild, which encouraged girls to inquire and learn, even after the end of formal schooling.

Dorothea’s achievements extended well beyond Cheltenham. She sent women, trained at her College, to set up schools based on her own educational methods in this country and abroad. She founded St Hilda’s College, Oxford which enabled women to access an Oxford University education. Another St Hilda’s foundation grew out of the ambitions of her Guild members to serve their community. Although the site has moved, ‘St Hilda’s East’ still remains today, fulfilling the purpose for which it was conceived – combatting deprivation and social exclusion through education, recreational provision and social care. Of the many other diverse social causes that Dorothea championed were organizations to help women who had suffered abuse and degradation and the Women’s suffrage movement. She became vice-president of the Central Society for Women’s Suffrage in 1900 and whilst she abhorred militancy, she firmly believed that a women’s vote was essential to ensure much-needed social reforms.

Dorothea Beale was a remarkable woman. She helped to breakdown prejudice and pioneer huge changes in the perception of women. She showed that it was possible and desirable to educate girls to a high intellectual standard and she encouraged women to go out into the world and ‘make a difference’. Although she was not a feminist in the modern sense of the word and, for example, still believed in the traditional feminine virtue of humility, despite encouraging those she educated to be self-reliant and independent, it would be perverse to deny that she was anything other than a great educational pioneer and reformer. She certainly deserves to be more widely recognized than she has been for her ground-breaking achievements.

Order your copy of Pioneering Women’s Education here.