Women’s History Month – Kim Thomas

Good food, clean clothes and ‘every comfort’: life in nineteenth century Broadmoor

In May 1863, eight women travelling by horse-drawn coach arrived at a large, new redbrick building in the small Berkshire village of Crowthorne. The building, a hospital, was set in 130 hectares of farmland, tree-lined terraces and lawns, and surrounded by countryside. It was an idyllic location in which patients could rest and recuperate.

This was no ordinary hospital, however. This was Broadmoor, Britain’s first asylum for criminal lunatics, and these eight women were to be its first patients. All had transferred from Bethlem Asylum in London, better known as Bedlam, and six had killed or wounded their own children. The member of the group whose name appears first on the Broadmoor register is Mary Ann Parr, a 35-year old labourer who had suffocated her illegitimate newborn baby. She had already spent 10 years in Bethlem at the time of the transfer, and she was to remain in Broadmoor until her death at the age of 71.

Broadmoor occupies a unique place in the popular imagination. We have all heard of it, and the name alone is enough to strike terror into the soul. Most of us associate it with serial killers like Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, or Kenneth Erskine, the Stockwell Strangler. Ronnie Kray, one of the notorious Kray twins, was in Broadmoor from the time of his conviction in 1969 until his death in 1995.

Yet there is a very different story to tell about Broadmoor. For the first few months of its existence, its patients were all female, and even after the men began to arrive, about 100 of the total 500 patients were women. Most of the women, like Mary Ann Parr, were from impoverished, working-class backgrounds, and two-thirds were illiterate. Many had previously worked as domestic servants or had brought up large families while their husbands worked as factory hands or coal miners.

Broadmoor had two types of patient: the first group, the majority, consisted of those who had committed a terrible crime, such as murder or arson, but had been found insane by the court. The vast majority of the women in this group had killed their own child, not always a newborn, but usually while in the grip of postpartum insanity. The second, smaller group consisted of petty criminals who had been declared insane in prison and then transferred to Broadmoor.

Most of us imagine that being sentenced to spend an indeterminate of time in Broadmoor must have been a terrifying experience. We can picture all too easily a Victorian asylum with its cruel disciplinary regime that included straitjackets, beatings and cold baths. By no means all asylums were like this, however, and Broadmoor chose a very different approach. The guiding principle was one of “moral therapy”: helping patients recover by means of a calm environment, exercise, fresh air and plain food. Patients who were considered mentally well enough were expected to work. Jobs were allocated according to sex, with the women assigned to work in the laundry or mending clothes.

Broadmoor’s early superintendents prided themselves on not using restraints such as shackles or straitjackets. Not only that, they did their best to make Broadmoor a restful place to stay. The male and female wings were strictly segregated, and the women had a dayroom where they could sit and chat, play chess or cribbage, read books or magazines, or play the piano. There were entertainments, such as a brass band, and the asylum also held a women-only dance once a fortnight. Patients were allowed visitors, so some women were fortunate enough to be visited by their family, though for many distance and cost would have made it impossible.

For women who had spent much of their lives toiling in unsanitary living and working conditions, life in Broadmoor, with its regular meals and fresh air, would have been easier than life on the outside. One (male) patient wrote home that Broadmoor was “pleasantly situated, has an extensive view and is very healthy… We have good food, plenty of clean clothes, good beds and bedding, and every comfort that one need expect.” He added that the patients were “treat[ed] with kindness by the officials placed over us, [and we] have free conversation among the other patients.”

As they worked alongside each other, there was opportunity for friendships to develop. Broadmoor’s rich archive includes a letter from a former patient to the superintendent asking after her friend, who is still there, and inviting her to come and live with her and husband when she is released.

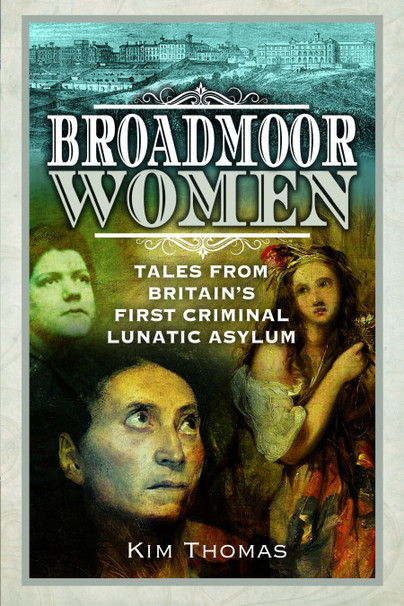

In my book, Broadmoor Women, I tell the stories of seven women who spent time at Broadmoor in the nineteenth century. Each of the women had terrible personal histories that led them to be detained in a criminal lunatic asylum: six had killed someone, and one had attempted murder. Yet of the seven, only one died in Broadmoor. The rest recovered their sanity and were allowed home to their families. For some, this was a welcome outcome, but for others, it was less so, as it meant returning to a miserable domestic situation. Rebecca Loveridge, a mother of seven, was sent to Broadmoor after drowning her baby daughter and attempting suicide. After only two years, she was discharged, returning to her violent husband, whose abusive behaviour had led her to a state of despair in the first place.

Today’s Broadmoor is a very different institution from its Victorian counterpart. The red brick buildings, now considered unsafe and poorly designed, were replaced in 2019 by a brightly-painted modern building with plenty of natural light and access to a central garden. Women are no longer admitted to the hospital, and it houses just over 200 patients. But we shouldn’t be in a rush to forget what Broadmoor, in its heyday, represented: not a cruel institution for punishing criminals, but a place that was enlightened enough to provide patients with a gently nurturing environment designed to help them recover.

Broadmoor Women is available to order here.