Women’s History Month – Kathryn Atherton

How did the suffragettes come to accidentally launch a national folk revival?

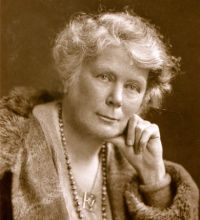

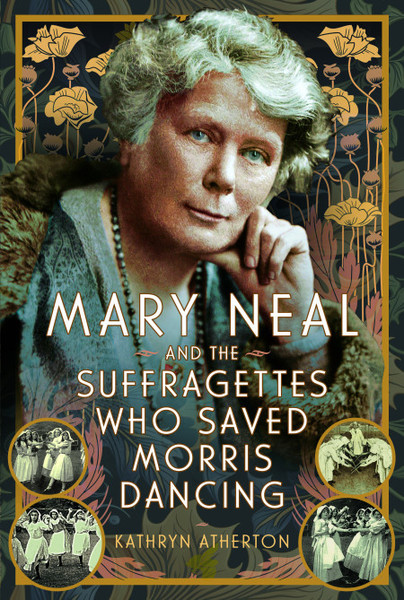

If it was not for militant suffragettes and a group of impoverished girls from the slums of London Morris dancing might be extinct in England today. Property damage and country dancing are strange bedfellows and yet it was girls who had never seen the countryside and their window-smashing leaders who rescued the dying dances at the beginning of the twentieth century and popularised them across the nation. In ‘Mary Neal and the Suffragettes who saved Morris Dancing’, I explore the story of Mary and her lifelong friend and collaborator, Emmeline Pethick, two women at the heart of Mrs Pankhurst’s militant campaign.

So how did I come across this story?

In a previous life I was a lawyer, working in Lincoln’s Inn. I came across the name Pethick-Lawrence when I passed a plaque commemorating the London HQ of the Women’s Social and Political Union next to the Royal Courts of Justice, on my way to work. I had never heard of Emmeline Pethick, and never enquired further. But on moving to Surrey I began to research the history of the area and came across a house known locally as ‘the suffragette house’. It had been the country home of the very same Emmeline Pethick and her husband Frederick Lawrence and was infamous as the country home of the militant campaigners.

Without Emmeline (and Fred) we might not be talking about the Pankhursts or the militant campaign today. The WSPU’s first London office was their apartment; as treasurer Emmeline effectively ran Mrs Pankhurst’s organization until a bitter split in 1912. She was imprisoned and forcibly fed and the contents of her Surrey home were sold at auction on the orders of the Director of Public Prosecutions. My book on Emmeline and her husband – ‘Suffragette Planners and Plotters, the Pankhurst/Pethick-Lawrence story’ – was published by Pen & Sword in 2019.

But there was a fascinating aspect to the story that could not be told in that book. Before becoming involved with the campaign for the vote Emmeline had established a groundbreaking girls’ club, The Esperance, in Camden, with her life-long friend and collaborator, Mary Neal. While Emmeline’s energies were subsumed into the campaign for the vote, Mary (also a member of Mrs Pankhurst’s organising committee) found herself leading a folk dance revival which brought together hunger-striking daughters of the aristocracy and young women from the slums in the fight to improve women’s lives. It was a strange story that had to be told.

Who was Mary Neal?

Mary, like Emmeline, was a well-to-do young woman who moved from a comfortable home to volunteer with the West London Methodist Mission. Together they sought to alleviate the suffering of those who lived in the squalid tenements around St Pancras. But they soon became disillusioned with the Mission’s limited aspirations and formed their own club for young women whose lives were otherwise hard and joyless. The Esperance established one of the first holiday hostels for working people. It also introduced the girls to political action, trades unionism and the Labour movement. Appalled by the conditions of the girls’ lives, Mary and Emmeline came to realise that the law did not protect women from economic, sexual or physical exploitation; until women could vote, they concluded, women’s lives would not improve.

As Emmeline became the organising force behind the militant suffrage movement, Mary introduced the girls to folk dance. With the encouragement of suffrage supporting artist Laurence Housmann, the girls gave demonstrations to the public, and were invited to teach across the country; within a year they had taught in nearly every county in England. Mary and the girls were embedded in the militant campaign, dancing at events, working in its offices, raising funds and marching in processions. Mabel Tuke, secretary to the militant campaign, wrote long pieces about the dance in ‘Votes for Women’ magazine; Sylvia Pankhurst painted the dancers’ feet, and Lady Constance Lytton, one of the movement’s most notorious hunger strikers was recruited to the campaign through the Esperance dancers.

Mary saw the dance is an extension of the campaign for women’s equality; she was taking the despised girls of the slums out to teach the wealthy and the influential; girls of little education who had been denied access to their heritage and culture, were respected for their expertise and skill. For Mary it was a glimpse of an aspirational world for the youth of England: her girls were being the change they wanted to see.

But not everyone was happy. Much has been written about Mary’s long public dispute with the folklorist Cecil Sharp who was later credited with beginning the Morris revival. I wanted to explore that dispute (which eventually saw Mary pushed out of the movement) in the context of the politics of the time and the campaign for the vote, which, with its increasingly radical tactics, was very divisive. Had the Esperance not been so embedded in the suffrage movement, might Sharp have been able to forgive the dancers all the things he accused them of in their long battle for supremacy in the dance movement?

Mary lost out to Cecil Sharp; Emmeline found herself ejected unwillingly from the WSPU by Mrs Pankhurst. Neither has been given their due by history.

My research has taken me to Oxford, Cambridge (where I nearly froze despite wearing coat, hat and gloves at Trinity College library on a snowy February day), to the Museum of London, the British Library, the LSE, the English Folk Dance and Song Society, Royal Holloway’s archives, and the Women’s Library. Along the way unseen photographs and caches of papers have come to light, shared by the Pethick family, and by Mary Neal’s great niece Lucy Neal. Finally the story of these extraordinary women who established two celebrated – and unexpectedly linked – national movements can be told.

Order Mary Neal and the Suffragettes Who Saved Morris Dancing here.