Women’s History Month – Julia A Hickey

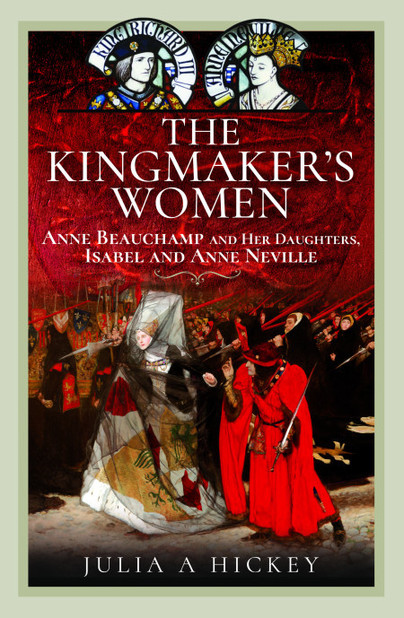

The Kingmaker’s Women: Anne Beauchamp and her daughters. Isabel and Anne Neville

Three weddings and no need for a funeral

A double wedding

Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury and Richard Beauchamp 13th Earl of Warwick both recognised that death was never far away, either on the battlefield, by disease or unforeseen misadventure. The marriage of their children provided an insurance against their own deaths while their heirs were underage and likely to become wards of the Crown. It was agreed that Warwick’s heir, Henry Beauchamp would marry Neville’s daughter Cecily at the same time that Salisbury’s heir, Richard, would marry Henry’s younger sister, Anne. Child marriages were relatively rare by the fifteenth century, although there are some notable exceptions, the most famous being the marriage of Lady Margaret Beaufort to Henry VI’s half-brother, Edmund Tudor.

The double marriage, recorded by the Tewkesbury Abbey Chronicle, was celebrated on 4 May 1436 at Abergavenny. The brides were both about 10-years-old. Canon law permitted children to enter into marriage as young as 7 years old, but it was more a legal agreement demonstrating an intention to marry as soon as the bride and groom reached an appropriate age. Neither Anne nor her husband had reached puberty, meaning that the vows they took were provisional and might be undone at a later date if they chose to renounce them, neither being old enough to affirm the marriage of their own free will, although Anne at 10 was old enough to know where her duty lay.

Anne’s groom was the youngest of all the participants, having been born on 22 November 1428. In theory the earliest that the marriage of Anne and Richard could have become legally binding was at the end of 1442 when Richard turned 14 years of age. The delay in the production of Neville heirs makes it difficult to be certain when Anne began living with her husband in the fullest sense of the word.

After the wedding, Anne journeyed to Middleham Castle in Yorkshire, where Richard continued his education under his father’s careful tutelage. It was an opportunity for a marriage based on political alliance to become one of companionship, if not love. No one could have anticipated that Henry Beauchamp would die soon after he succeeded to his father’s titles and that his young daughter, 15th countess of Warwick in her own right, would die just three years later in 1449 bringing the Beauchamp line of earls to an end. The child marriage unexpectedly turned Anne’s husband into the 16th Earl of Warwick and one of the most powerful men in the country.

A forbidden union

On 17 May 1469 the Earl of Warwick was in Sandwich with Countess Anne and both their daughters, overseeing the fitting-out of his fleet. King Edward IV’s brother, George, Duke of Clarence arrived in Sandwich at the beginning of June. The earl’s brother, George Neville, Archbishop of York, also arrived at Sandwich where he blessed a new vessel named the Trinity commissioned by Warwick as his flagship.

The Nevilles accompanied by the Duke of Clarence sailed to Calais soon afterwards. On either 9 or 11 July 1469, Clarence married Isabel Neville, in defiance of King Edward IV’s command. The earl had taken the precaution of securing a papal dispensation permitting the marriage despite the fact that the couple were related within a prohibited degree. He did not wish for the king to find a way of having the union annulled at a later date. Isabel and George’s wedding was recorded by The Great Chronicle of London because of its political significance.

There is no record of what Isabel might have thought of her husband, her elevation to the king’s immediate family or the possibility that she might be queen if Clarence ever ascended to the throne. Her new husband was handsome, clever and charming. At 19, he was just a year older than Isabel and she had known him since childhood.

The Kingmaker’s bargain

Warwick and Clarence’s plans to seize power from Edward came to nothing and they were forced to flee England in May 1470. In June it was whispered that the earl had agreed to a rapprochement with the Lancastrian faction. It was not a particularly palatable alliance for either Warwick or Henry VI’s queen, Margaret of Anjou. Ensuing negotiations included 14-year-old Anne’s marriage to Edward of Lancaster who was now 17 years old and determined upon the destruction of the House of York. It did not matter that Anne did not know Edward or that she would be entering a household with reason to hate the name Neville.

Clarence realised that it was unlikely Warwick would continue to support his desire to become king. His own self-interest and the mediation offered by his sisters and mother swayed Clarence’s resolve. It is not known what Isabel’s view of the matter might have been but Anne’s marriage to Prince Edward ensured that the two sisters would be on different sides by the time that the battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury were fought in the spring of 1471.

No need for a funeral

When Anne Beauchamp, Countess of Warwick learned of her husband’s death at the Battle of Barnet on 14 April 1471, she sought sanctuary at Beaulieu Abbey. She remained the 16th Countess of Warwick in her own right and retained all her estates and properties. She was also entitled to her dower rights as a widow, even if her husband was attainted as a traitor. In theory, the countess was now a very wealthy and independent woman.

Whatever personal affection King Edward had for Countess Anne was laid to one side so that she could be separated from the land and power which she represented. In 1474, Parliament declared the countess to be legally dead.

Order The Kingmaker’s Women here.