Women’s History Month – Catherine Curzon

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the Charitable Queen by Catherine Curzon

When Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz arrived in England to marry King George III in 1761, she was just 17 years old. The young king, whose mother had been a political mover and shaker, told his wife that she was to avoid politics at all costs: whatever happened, she must not meddle. It was a command that the queen took seriously, and even when the Regency loomed as her husband’s mental health declined, she never sought political influence.

Charlotte’s passions were for anything but politics, and who can blame her? . She loved the opera and theatre and was a huge fan of actress Sarah Siddons; she collected jewellery and established menageries of exotic animals, but her true love was philanthropy. In fact, when George’s spies had been keeping an eye on the young princess to see if she’d make a good queen, they’d been concerned to discover that she liked to score big at the card tables, before disappearing for hours. Suspecting all manner of improper interests, they were relieved to discover that she actually spent those secretive hours distributing her winnings amongst the poor. Charlotte herself had not been raised in immense wealth, but instead in a court that was always looking to make ends meet. Chased from their home by the invading armies of Frederick the Great, her widowed mother had raised her daughters to appreciate what they had, even when that was very little indeed, especially by the standards of the royal family she eventually married into.

Though Charlotte’s predecessor on the throne had been devoted to politicking and intrigue, and her mother-in-law had incurred the wrath of the public by her perceived meddling and cronyism, the unassuming new queen preferred to use her influence in the pursuit of charity. As well as donations, patronages and more, she wasn’t above helping practically either, and was happy to mix with whoever might need her help. Stories were told in which the queen plucked a diamond out of her stomacher and gave it to a poverty-stricken Windsor clergyman, or of her generously sending two hogs to a starving family who had been kind enough to shelter the queen and their ladies during a flash storm. When their situation had improved, the householder’s grateful wife took a spare-rib all the way from Windsor to St James’s to say thank you, only to find herself given more gifts by the queen.

Queen Charlotte’s famed charity soon spread across the royal palaces and exploded in a blaze of colour at Christmas 1800, when she put up the first Christmas tree a British royal household had ever said. She hung presents from the branches of the traditional German yew and laid on a dinner for 60 poor local families, giving them a Christmas they would remember forever. As the bill for Queen Charlotte’s generosity mounted to £5,000 and kept going, she showed no sign of flagging. She funded housing and education for so-called fallen women and established funds to care for military orphans, taking a keen interest in reports of their welfare.

Perhaps the most famous and long-lasting of the queen’s charitable endeavours was also the most uncharacteristic: Queen Charlotte’s Ball. Charlotte hated being in the limelight but for her birthday in 1780, she agreed to grit her teeth and host an elaborate formal ball to raise funds for her charities. Standing beside a vast birthday cake for hours on end, the queen greeted debutantes as they were presented to her to mark their coming out in society. With the money raised from the ball, she funded what is now Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Hospital.

The Ball and its traditional birthday cake became an annual event despite Charlotte’s loathing of the limelight, and continued for more than a century after her death. It became a pivotal occasion in the social calendar of the upper classes and the more popular it became, the less Charlotte enjoyed it. She felt hemmed in and overwhelmed by the crowds who, as Horace Walpole wrote, “squeezed, and shoved, and pressed upon the Queen in the most hoyden manner. As she went out of the Drawing-room, somebody said in flattery, ‘The crowd was very great.’– ‘Yes,’ said the Queen, ‘and wherever one went, the Queen was in everybody’s way.”

As the king’s mental health grew ever more strained until he didn’t recognise his wife at all, and her quarrels with her daughters grew more furious, it was philanthropy to which she turned for comfort. It was very fitting that the last public appearance of this generous queen was not at a glittering social occasion or some other rarefied event, but at a day honouring those who worked in charitable fields.

On 29th April 1818, Queen Charlotte made her final public appearance when she attended a prizegiving ceremony at the Mansion House in honour of the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor. Here she made a personal donation of £500 and spoke with the celebrated reformer, Elizabeth Fry. Unlike Queen Charlotte’s Ball, where she painted on a smile and posed beside an absurdly oversized birthday cake in rigid formality, at the Mansion House event the queen was delighted to mingle with the children who had benefited from the educational initiatives being celebrated. None of them were debutantes nor the leading young lights of the ton, but that did nothing to deter her. Here, where she could meet the children her philanthropy had helped in person, the queen was content. By the end of 1818, Queen Charlotte was dead; there can have been no more fitting last place for her to have met the people she had striven all her life to help.

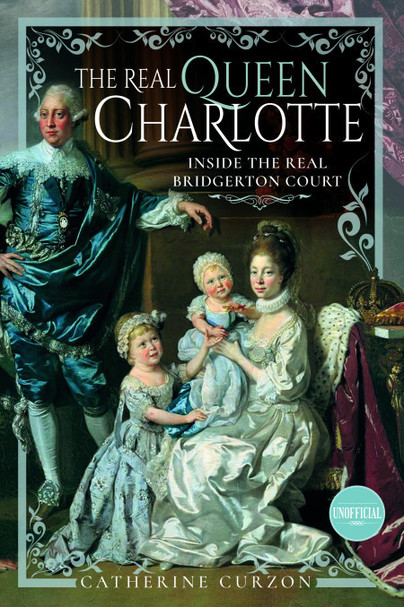

Order your copy of The Real Queen Charlotte here.