Women’s History Month – Caroline Roope

Five Intrepid Women of the 19th Century

Whilst nineteenth-century Britain was establishing itself as a powerhouse of industry and innovation, a handful of plucky women were forging their own paths abroad – often armed with machetes, pistols and more than a little derring-do.

Travel and exploration in the nineteenth century was not for the faint-hearted. There was the constant threat of disease, as well as the dangers that came with coping with extreme climates. Journeys were perilous; and transport, if there was any, was basic. Despite this, the century saw women donning their thickest skirts and toughest boots and taking a surprisingly big step out of their domestic sphere and into the unknown.

Fortunately, many of them left behind a written record of their adventures in the form of diaries or travelogues, and what they reveal turns nineteenth century sensibility on to its stove-pipe-hatted head. So without further ado, here are five fabulous women who had no intention of letting their gender (or their skirts) get in the way of their wanderlust…

Kate Marsden – Sledging in Siberia

When English nurse Kate Marsden (1859-1931) tried to board a sledge to Yakutsk in 1890 to help cure a Siberian leper colony it took the efforts of three Russian policemen to help hoist her onto it – such was the stiffness and bulk of her numerous layers. Marsden’s outfit [see image] included ‘a whole outfit of Jaeger garments’ – a flannel lined ‘body,’ a thickly-wadded eiderdown ulster with a fur collar to shield the neck and face, a floor-length sheepskin, and over that, a fur coat of reindeer skin. Underneath she wore thick Jaeger stockings, covered with a further pair of gentleman’s hunting stockings. For her feet she wore a pair of knee-high Russian boots made of felt and covered those with a pair of brown felt valenki (traditional Russian winter footwear).

Clothing, however, was the least of Marsden’s worries. Her ‘Mission’ involved riding two-thousand miles across one of the most inhospitable regions on earth to find a magic herb that grew deep in the Siberian Forest – a herb that she believed would cure leprosy. It didn’t – but she was able to console herself with the 18kg of Christmas pudding she took with her.

Annie Londonderry – Spinning around

Annie Londonderry’s (1870-1947) notoriety as the first female to bicycle around the world coincided with the cycling craze of the late nineteenth-century. Annie was an unlikely candidate for such a feat, having confessed she’d never even ridden a bike before her marvellous stunt. But with a ‘devil may care’ attitude, Annie decided to quite literally, ‘spin’ her way around the world – embarking on a series of adventures, and some very tall tales. Hunting tigers with royalty, being sent to a Japanese prison with a bullet wound, exaggerated accidents and injuries – all of this and more made it into Annie’s narrative. Fortunately for Annie, her ‘exploits’ brought more column-inches for her numerous sponsors. She became part of a wider movement concerned with dress reform and gender equality. The bicycle was both a literal and symbolic vehicle for social change at the end of the nineteenth century, and Annie’s globetrotting enterprise provided an opportunity to demonstrate women’s new-found freedom.

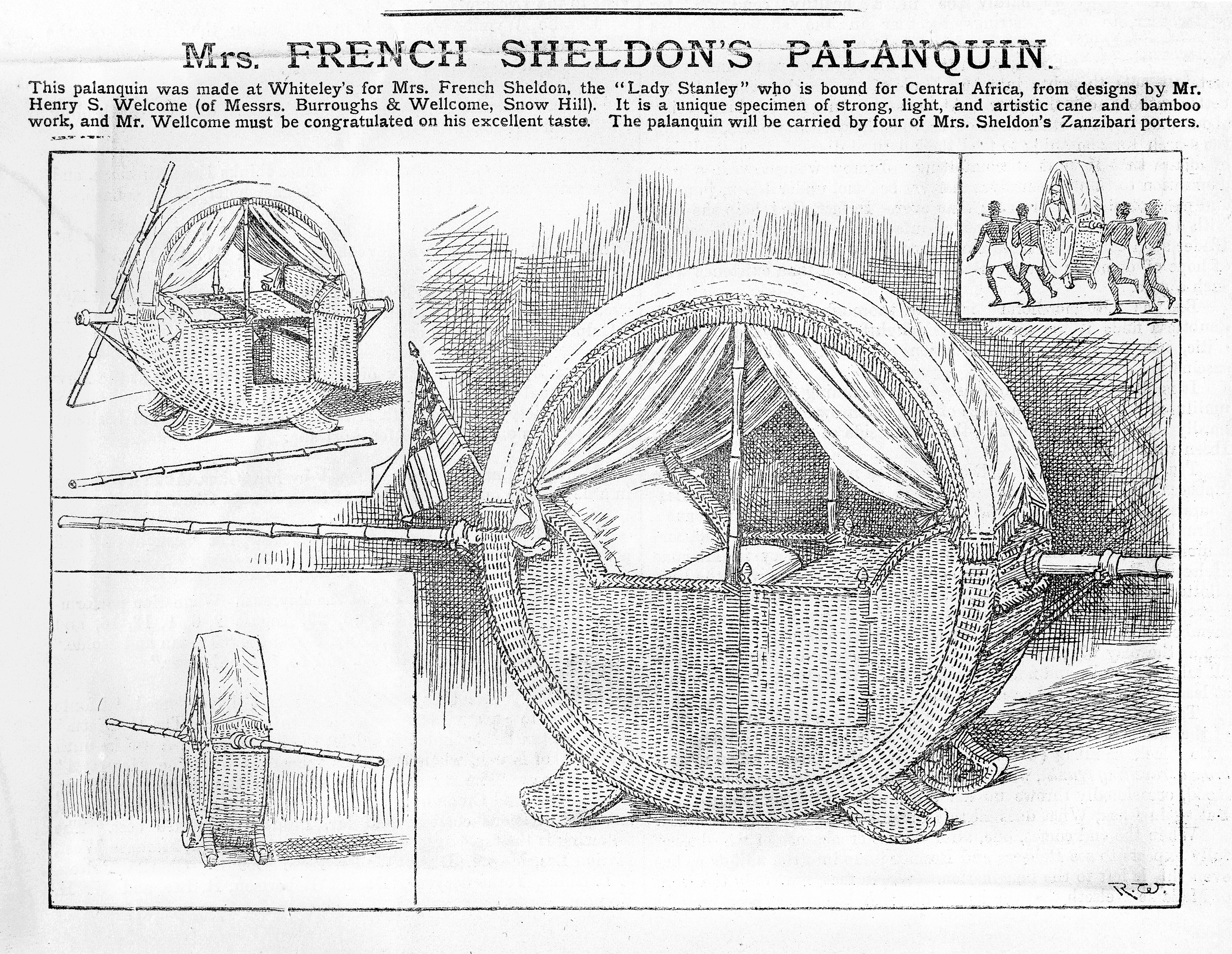

May French Sheldon – The original first-class passenger

For some, luxurious habits die hard – even in the African wilderness. American explorer and ethnographer, May French Sheldon (1847-1936) liked to travel in style. The bombastic Sheldon – whose entourage included 153 porters, a personal masseuse, a portable bath, Parisian silk dresses and a blonde wig – journeyed into the African Interior in 1891 in an enormous wicker palanquin strewn with luxury furnishings. Sheldon may have reeked of the ultimate white traveller abroad – her native male porters called her ‘Bebe Bwana’ (woman master) – but behind the imperialist façade lurked an extremely talented and courageous scientist with a genuine interest in observing and documenting other cultures – which she helpfully condensed into a travelogue for us to all enjoy.

Annie Boyle Hore – Mum on a mission

Annie Boyle Hore (1853-1922) found out the hard way that missionary work and motherhood seldom make an agreeable pairing. Her charmingly titled account, To Lake Tanganyika in a Bath Chair, relates the slightly unusual circumstances under which she found herself travelling into the African interior.

Annies scientist husband Edward was commissioned to assess the viability of prospective routes for missionary groups. This was almost certainly a nice way of saying that whether the routes were feasible or not depended on whether they all made it back from the crocodile-infested swamps in one piece.

Annie and the Hore’s baby Jack were a necessary appendage to this slightly barmy scheme since Edward’s remit needed to establish if women could undertake the routes. Jacks’ survival would be a useful barometer of just how feasible the journey was. Edward was convinced that conveying his wife across Africa in a wheeled wicker bath chair was the answer. And because he was a man, everyone nodded and agreed.

In between dealing with the needs of a fractious child in searing heat, the journey also included the threat of hyena and crocodile attack, a gun fight, an enormous flood, famine, and severe illness. But it was eventually concluded to everyone’s satisfaction. ‘The bath chair is put away in the store, and my story must end,’ Annie writes poignantly. And with that, like many of her adventuring comrades, she disappears from view.

Susanna Moodie – Moodie by name…

Born in Suffolk, England, Susanna Moodie (1803-1885) was a reluctant traveller. Having been promised a new life in the ‘land of opportunity’ and dragged halfway across the world by her husband, she was rather upset to find herself in the Upper Canadian wilderness, which at the time was populated by wolves, bears and unruly neighbours (both human and animal). Her first home was a miserable hut that Susanna mistook for a pig-sty when they arrived but she soon settled into a life of eating squirrels – or if times were really bad, family pets – sharing belongings with just about everyone in a three-mile radius; having said belongings ‘borrowed’ by numerous friends and neighbours (never to be seen again), sub-zero temperatures, and living under the constant threat of one’s log cabin burning down in order to keep it warm. But apparently there were riches aplenty to be had, so it was worth it.

As the youngest daughter of a genteel family, Susanna was thoroughly unsuited to a life of roughing it in the bush. Her travelogue was a candid account of her ordeal, which she ardently hoped would prepare prospective immigrants for the trials ahead. Or put them off the idea completely. She spent seven years in the wilderness, and poor Susanna hated every minute of it.

You can read more stories of other amazing female explorers in my book, 19th Century Female Explorers, available here.