Witch Week – The Puritan, the Pirate Captain and the Salem Witch Trials

Guest post from Pen and Sword author Nicky Nielsen.

At noon on July 19th 1723 a row of twenty-six prisoners, chained and manacled, shuffled out of the little town gaol in Newport, Rhode Island. Accompanied by the jeers of a huge crowd of men, women and children, the condemned made their way slowly down to Gravelly Point. There, they were lined up by a large improvised set of gallows and, simultaneously, hanged by the neck until dead. Their last gasping breaths, their moans of pain as the rope slowly suffocated them, their gurgles and bulging eyes caused such an awful spectacle that even the most hardened watchers had to look away. Above the heads of the dying men, representatives of the court that had condemned them nailed the black flag under which they had sailed. The men were pirates. Members of the pirate captain Ned Low’s crew. They had been captured after a spree of plunder and violence lasting several years which had terrified sailors and passengers from the Bay of Honduras, to the Grand Banks, the Azores and the coast of Africa.

The authorities in New England celebrated wildly. They saw the mass execution in Newport as a divinely inspired victory against the demonic scourge of piracy. One man in particular celebrated more than most: Cotton Mather was, like his father Increase, a celebrated and influential puritan writer. His books, articles and pamphlets on every topic related to living and, in particular, sinning had helped define puritan thought throughout the American colonies. From his pulpit, Mather regularly worked himself into a rage, admonishing his congregation about the drinking, whoring and sinning the pirates hanged at Newport had undoubtedly committed: “Among the dolorous ejaculations of dying pirates, how often do you hear them confessing: my grieving and leaving and scorning of my parents has been that which has brought the dreadful vengeance of God upon me!”

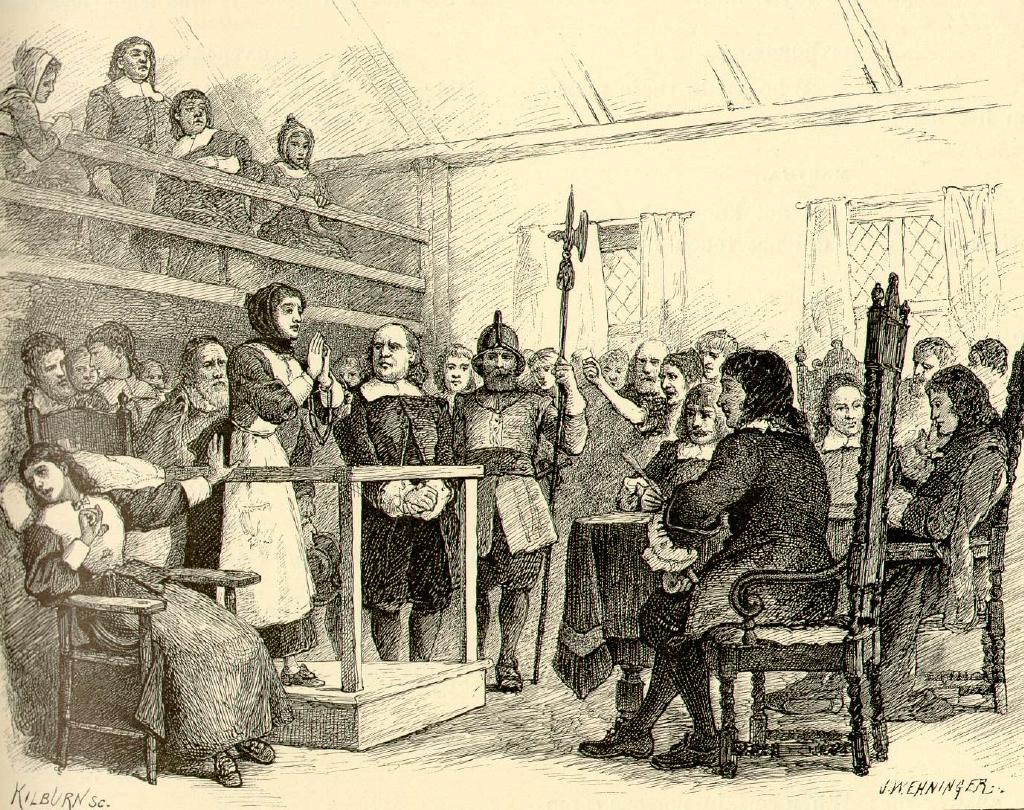

But piracy was not the only topic that occupied Mather’s time. He is remembered in history primarily for his role as a driving force behind the infamous witch trials in Salem and Andover which took place in 1692. He did not himself sit in judgment of those poor souls who went to the gallows for the imagined crime of witchcraft. He instead provided spiritual advice, guiding the judges and carefully shaping public opinion. The year after the witch trials ended, he wrote a lengthy account of them – Wonders of the Invisible World – defending their necessity and declaring his utter belief in the presence of invisible demonic forces and witchcraft. He had experience. As early as 1688, four years before the Salem Witch Trials, he had himself investigated several cases of witchcraft one of these resulting in the capture and execution of the Catholic women Goody Glover.

After the Salem Witch Trials ended, at the beginning of the 18th century, Cotton Mather took up a post as the preacher to Boston’s Second Church. There, among his congregation sat a man whose face we do not know. We have no description of him, other than that he may have had a beard, and also, may have been rather physically unappealing. His name was Edward, and he had grown up as a thief in London. In 1710 he had moved to Boston, gotten a job and settled down. Four years later he married Eliza Marble whose family had been directly involved in the Salem Witch Trials as well. In fact, one Joseph Marble, whose precise relation to Eliza is not clear, had sat on the Grand Jury that acquitted the last of the accused witches when the witch hysteria subsided. Joseph and his brother also helped post the bond for the two accused girls, Dorothy and Abigail Faulkner, so that they could be released from prison. The two girls, 12 and 9 years old, had not only been accused of witchcraft themselves, they had also seen their mother Abigail Faulkner Sr go to the gallows for the crime herself.

We do not know how the young Edward, sitting on his pew in Boston’s Second Church with his new wife, responded to the lectures, sermons and haranguing by Cotton Mather. But based on what happened next, we can assume that the preacher’s sermons left little impression on the English sailor. Mather frequently lectured on the wickedness of pirates and other criminals, on the need to respect authority and one’s elders. But when Eliza Marble died in childbirth, leaving Edward the single parent to their young daughter Elizabeth, something snapped in Edward’s mind.

He became violent, prone to drunkenness and unreliable. Finally, he lost his job and took hire onboard a logging ship going to the Bay of Honduras. And there, after being pushed beyond breaking point by the ship’s captain, Edward “Ned” Low took up a musket and fired the shot that would launch one of the most brutal pirate careers in history. The sailor who had come from London to Boston, who had been lectured by Cotton Mather, seen the aftermath of the Salem Witch Trials, who may even have met a young Benjamin Franklin – only a teenager at this point – going about his daily business, became a feared pirate captain: A man so wicked that his own crew declared themselves afraid to oppose him. His ultimate fate is unknown. Unlike his comrades at Gravelly Point, unlike the innocent men and women of Salem and Andover, he never faced a judge or a noose. He vanished out of history deep into the thickets of the Honduran jungle.

You can find out more about the nefarious Ned Low in The Pirate Captain Ned Low.