Why Henri Désiré Landru’s infamous list of murders may not have been complete

Guest post from author Richard Tomlinson.

In 1915 a convicted Parisian swindler on the run from the law acquired a little black diary to keep track of his increasingly busy life. Over the next four years, he filled his notebook with records of his transactions, from the gifts he bought for his many women friends to the one-way train tickets he purchased when they travelled with him to the country.

Eventually, he turned to a clean page and wrote out a list of 11 names and codenames in clear, legible handwriting, quite unlike the rest of his jottings. The list read: “Cuchet, J., Idem, Brésil, Crozatier, Havre, Collomb, Babelay, Buisson, Jaume, Pascal, Marchadier”. Shortly afterwards, on 12 April 1919, the swindler was finally arrested on suspicion of murdering two middle-aged widows. When the police ordered him to empty the pockets of his grubby yellow tunic, out came the notebook.

Henri Désiré Landru’s notebook is arguably the most infamous item of evidence in French criminal history. It is also a far more ambiguous document than the prosecution case against Landru pretended. The authorities claimed that the 10 women and one youth on Landru’s list were his only murder victims. Yet long-buried documents in Landru’s vast case archive indicate that he killed more women – possibly many more – during his terrifying rampage across First World War Paris.

From the moment of Landru’s arrest, at a dingy apartment near Paris’s Gare du Nord, the investigation was dogged by the police’s incompetence. It began with their hasty initial search the following day of the Villa Tric, Landru’s country house 50 kilometres southwest of Paris, where seven of the women on his list had disappeared, seemingly without trace. All the police found were the corpses of three dogs, buried in a shallow grave in the kitchen yard. Obligingly, the handcuffed Landru acknowledged that he had strangled the animals, even pointing to another nearby spot where he had buried a strangled cat.

A second search two days later of The Lodge, a house in the village of Vernouillet, 35 kilometres northwest of Paris, was equally superficial. The first four individuals on Landru’s list had vanished here during his brief tenancy from December 1914 and August 1915. Yet it took investigators only a few hours to conclude that The Lodge and its extensive back garden contained no usable forensic evidence, because of the passage of time.

On 29 April 1919, a full police and forensic team returned to the Villa Tric for a more thorough investigation which would last a full week. After only a few hours, they uncovered a scattering of burnt bone fragments and women’s apparel beneath a pile of leaves in a garden shed. The bone debris was clearly compelling indirect evidence against Landru; at the very least, he was obviously a murderer. Yet without the benefit of DNA evidence, forensic scientists could not link the fragments directly to the seven women who had gone missing at the Villa Tric. It was possible that some or all of these charred remains came from other nameless victims.

In the end, Gabriel Bonin, the investigating magistrate charged with assembling the case against Landru, fell back on the list in the notebook to paper over the gaps in the forensic evidence. Bonin argued that the 11 names represented Landru’s complete list of his murders. From this starting point, Bonin built a case of boiled-down simplicity. Landru was a lethal marriage swindler, motivated purely by financial gain, who in a lethal twist had killed his victims to prevent them going to the police.

Bonin further maintained that Landru had acted alone, despite the strong circumstantial evidence that his wife and four adult children had been accomplices to his thefts from several of the missing women. All the women had been besotted by Landru, and all had been murdered in circumstances which were “reproduced identically”, Bonin concluded.

The logical flaws in Bonin’s simplistic narrative were plain. Six of the women on Landru’s list had been extremely poor and therefore implausible targets for a marriage swindler. But as I learned when working through Landru’s case archive, a far greater difficulty existed right at the start of the case.

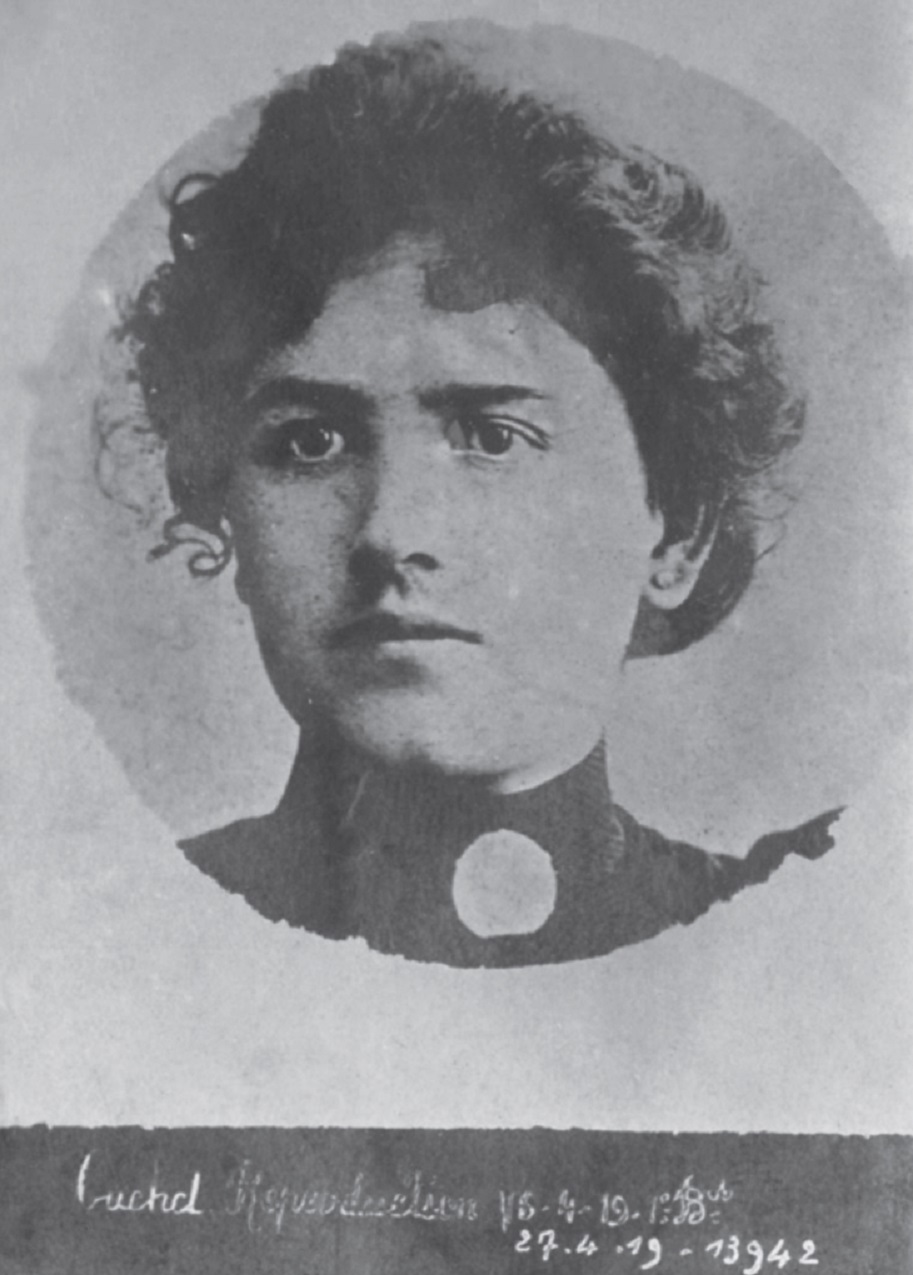

Jeanne Cuchet, a pretty, 39-year-old widowed seamstress, was the first name on Landru’s list, and the first known woman to vanish in early 1915. She was cast by Bonin as the template for all the supposedly identical murders which followed. Yet Jeanne’s disappearance was utterly different from the others in three crucial respects. Jeanne and her 17-year-old son André were the only individuals on the list who had discovered Landru’s true identity as a criminal on the run. They were the only double murder on the charge sheet, and André was the only male victim.

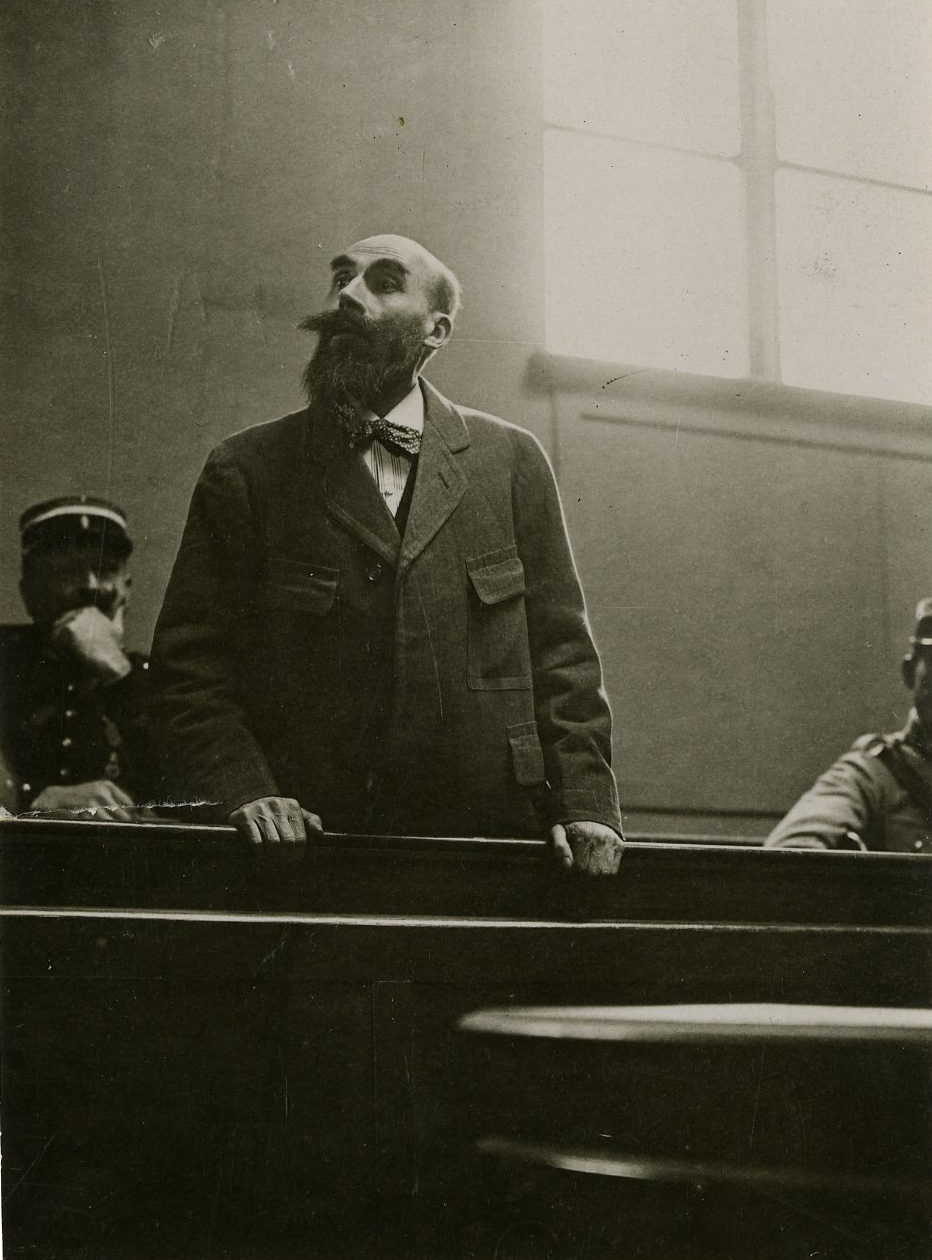

At Landru’s trial, held in Versailles in November 1921, the prosecution skated over the problems presented by Jeanne and André when compared with the succeeding victims. It was a weak start to a prosecution case that Landru’s brilliant defence attorney Vincent de Moro Giafferri gradually enveloped in so much doubt that he almost saved his client’s head.

In the end, the jury found Landru guilty of the 11 murder charges, but only by a majority verdict with three dissenting jurors. Still protesting his innocence, Landru was guillotined at dawn on 25 February 1922 outside the gates of the main prison at Versailles.

After Landru’s execution, his infamous notebook, like the women he had allegedly murdered, simply disappeared. It seems likely that a detective called Riboulet kept the notebook as a souvenir, after reproducing most of the contents in his highly unreliable 1933 memoir of the case. Yet even without the original notebook, there is enough evidence in Landru’s case archive to indicate that the list was almost certainly incomplete. Indeed, it is conceivable that Landru was one of the most prolific killers of women in history.

For a start, Landru did not acquire the notebook until the spring of 1915 and did not begin to make detailed notes in it till a year later. I proved from witness statements and police reports that many of Landru’s engagements with women were never recorded in the notebook. Three of those witnesses had disturbing testimony about Landru’s activities at the Villa Tric which was ridiculed at his trial, because their stories did not fit chronologically with the prosecution’s timeline, as laid down by the dates when the 11 individuals on the list had vanished.

But the most troubling evidence was the police’s mendacious claim that they had traced and identified all the official tally of 283 women whom Landru had contacted during the war, mostly via lonely hearts adverts and marriage agencies. This was untrue. A note on the same police report, never published until I found it, acknowledged that “the identity of 72 individuals had not been established”.

Based on this evidence, I believe a far more persuasive plot exists than the one which Bonin cobbled together from the list in Landru’s notebook. This plot begins, not with the notebook, but the strong possibility that Jeanne Cuchet made the fatal mistake of trying to blackmail Landru.

………………………………………………………………………………..

Landru’s Secret is available to order here.