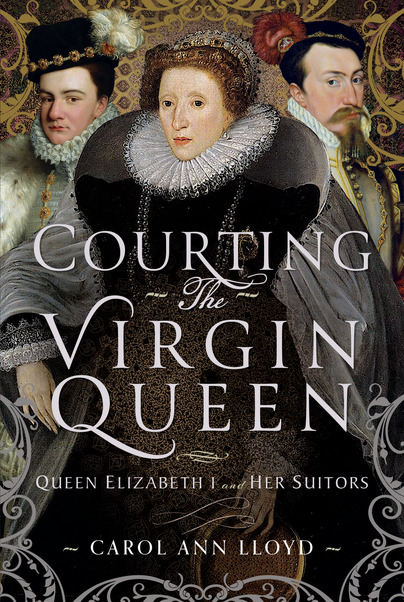

The Virgin Queen’s Choices Might Make Sense to Women Today

Guest post by Carol Ann Lloyd.

When Elizabeth Tudor came to the throne in 1558, the Spanish ambassador wrote, ‘Everything depends upon the husband this woman may take’. There was no question IF the new Queen would marry; the question was which of her many suitors she would choose. Marriage was an issue throughout her reign. The queen was questioned by parliament about her plans to marry, her privy council encouraged and cajoled her to marry, and foreign visitors brought offers they were certain would be accepted. Questions of religion, foreign support, domestic hierarchy, economics, trade routes, and exploration revolved around her marriage. Marriage was thought essential for a woman, especially a woman who found herself in the ‘unnatural’ position of ruling a kingdom. Previous English monarchs had married when they became adults. And the other women who had ruled as queen—specifically Mary I and Mary, Queen of Scots—had married. Surely, Elizabeth would do the natural, right thing and marry. Or would she?

Elizabeth’s early experiences with marriage were no incentive to take the step herself. Her father, Henry VIII, was not the greatest role model for marriage. He married six times, cast aside his first wife, beheaded his second wife who was also Elizabeth’s mother, saw his third wife die after childbirth, cast aside his fourth wife after six months of marriage, beheaded his fifth wife who was also Elizabeth’s first cousin once removed, and was outlived by his sixth wife.

She lived with her stepmother, Henry VIII’s widow Katherine Parr, in a happy setting until Katherine’s husband Thomas Seymour moved in. Whatever the specifics, Elizabeth was subject to unwanted actions and was haunted by the suspicion she had slept with Seymour and born his child. Eventually, Elizabeth was sent away from her beloved stepmother, who died before the two could reunite. Elizabeth was then interrogated about her relationship with Seymour by older men who were determined to implicate her in his plots against King Edward VI. Elizabeth escaped but was reasonably wary of courtship.

In 1558, Elizabeth became queen. Her early suitors included her sister’s former husband, Philip II, Eric of Sweden (first as prince, then again when he became king), William Pickering, and James Hamilton Earl of Arran. As time passed, along came Henri Duc of Anjou and Archduke Charles of Austria as support against foreign powers and religious wars became a real threat. Throughout, of course, there was Robert Dudley—Elizabeth’s BFF and probably the man she would have married had she not been queen and had his first wife not died in such controversial circumstances. Elizabeth’s final suitor, Hercule Francois (nicknamed her ‘Frog’) came along toward the end her reign. He was the only foreign suitor to come to England to court her, which he did twice. When he sailed away, Elizabeth’s real chance of marriage had ended.

In the face of universal expectation and some intriguing offers, even facing her country’s isolation and threats to her throne, Elizabeth made the decision to never marry. In her day, that decision was shocking. Most women, given the option, chose to marry. That was true for hundreds of years. Is it still true today? Let’s take a look.

In 2024, less than half the households in the US were headed by married couples, down from nearly 80 percent in 1949. Overall, fewer people are marrying in the US. In 2021, the Pew Research Center found that the rate of people without a partner increased by more than 10 percent from 1990, with 38 percent of adults defining themselves as single. Other studies show than over the past two decades the percentage of people who never marry rose from 21 percent to 35 percent. Pew has concluded that the increase of singles who never marry is significantly higher than the increase in those whose marriages have ended. Of particular interest is the fact that one fourth of Americans aged 40 have never married, a record high that could signal a real shift in attitudes about marriage.

Over the last five years, the proportion of adults in England and Wales who are married also dropped below 50 percent. The data on marriage percentages goes back to 1972, when the rate was above 50 percent and remained there until around 2018. In 2020, the number of marriages dropped to its lowest point since 1838. Even when taking the restrictions of COVID into consideration, the decline in marriages is evident: from 1989 to 2019, the number of marriages decreased by almost 37 percent. According to the Institute for Family Studies, the percentage of people who never marry rose by 14 percentage points over the past two decades, from 21 percent to 35 percent.

Dinah Hannaford, associate professor of Anthropology at the University of Houston, led colleagues in a search for the reasons for this change. As anthropologists, they connected the trends and statistics to societal changes and expectations. Some of the reasons they found for a reluctance for women to marry included infidelity, career opportunities, independence, and the option of living with parents or siblings. As Hannaford said, ‘As new opportunities open up for women to be full people without [marriage], they’re opting for that’ (‘Why are women opting out of marriage around the world?’, University of Houston, January 11, 2023).

In other words, today some women are following Elizabeth’s advice that she would ‘highly commend the single life’ (TNA, Elizabeth I to King Eric XIV of Sweden, 25 February 1560 (SP 70/11 f.74).

Why did Elizabeth never marry? We have no diary from her, no letter to a friend saying, ‘here’s why I never married’. Based on what we do know, perhaps we can make connections to unmarried women of today. Elizabeth had seen infidelity throughout her life, realizing that it was acceptable and even expected for royal men to amuse themselves with other women. Elizabeth loved her independence, and is reported to have once said, ‘I will have but one mistress here, and no master’. And finally, Elizabeth wanted control of her life as an independent monarch.

In a record of her address to her first Parliament, Elizabeth said, ‘This shall be sufficient that a marble stone shall declare that a Queen, having reigned such a time, lived and died a virgin’. In other speeches, she declared herself married to her country and in need of no other spouse. And in the end, she filled her own prophecy, living a dying as the ‘Virgin Queen’.

Courting the Virgin Queen is available to preorder here.