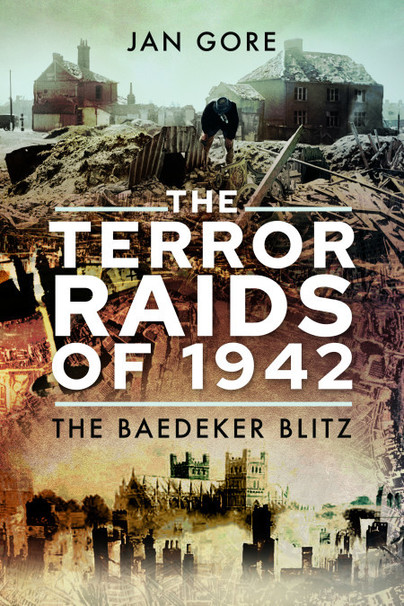

The terror raids of 1942: the eightieth anniversary of the Baedeker Blitz, by Jan Gore

Guest post from author Jan Gore.

This spring marks the eightieth anniversary of the Baedeker Blitz, when the Luftwaffe attacked a series of historic English cities: Exeter, Bath, Norwich, York and Canterbury. The attacks were a direct retaliation for RAF raids on equally attractive German cities, such as Lübeck. The “Baedeker” name referred to a well-known German guidebook, which listed historic buildings by their star ratings. ‘We shall go out and bomb every building in Britain marked with three stars in the Baedeker Guide’ the German Foreign Office announced in April 1942.

My book is the first full history of the raids for over twenty years. It describes the Baedeker Blitz from the point of view of the civilians who were its target, with graphic first-hand accounts and contemporary news stories.

The Luftwaffe strategy was to start by dropping flares to light the way for the aircraft that followed. Next came large numbers of incendiaries, to illuminate the area and to start fires. Then the HE bombs would begin, forcing people to take cover so that they were unable to extinguish the incendiaries. All the Baedeker attacks were at night. The initial attacks were a complete surprise to the inhabitants as the cities had not experienced raids for some time. People were often deeply asleep and slow to respond. By the time they reached shelter, bombs might already be falling. They could only wait in the dark, wondering whether the next bomb would be theirs.

Exeter was first to suffer a Baedeker raid, on 23 April. Most raiders missed their target and bombs fell over a wide area of the West Country. The next attack came the following night and later became known, with hindsight, as the “Minor” Blitz; first-hand accounts were emphatic that it was a terrifying experience. The sirens sounded just after midnight and bombs began to fall almost immediately. The raid lasted almost two hours and the aircraft came in two waves. About 60 HE bombs fell, along with 2,000 incendiaries. Whole families died in the bombing: grandparents, parents and children. 73 people were killed and about 6,000 houses were damaged, with many people made homeless.

Bath was the next target. There had been no attacks for over a year, so people were slow to take shelter when the sirens sounded just before 11 pm on 25 April. Incendiaries and HE bombs fell and the bombers came in low to machine-gun the streets. A family in the Circus wrote of hiding in their cellar as their house rocked from the explosions, while the former mayoress of Bath was killed, just before her wedding. The raid ended soon after midnight.

The fires were still burning from the first raid when the Luftwaffe returned four hours later. Heavy bombing began again, and several air raid shelters were hit, including the Scala. The Roseberry Road shelter suffered a direct hit, and twenty-eight of its thirty-one occupants were killed outright. The All Clear sounded just after 6 am. The two raids were so intense that there was no time to keep detailed records of the casualties for each attack. By the end of the night at least 240 people had died.

Exeter suffered a further attack on 26 April, with another twenty casualties. By now the city had experienced three raids in four nights. Increasingly people trekked out to the hills every night, preferring to shelter under hedges, face down to avoid being seen by enemy aircraft.

But it was Bath’s turn again. The raiders returned for a third attack on the night of 26/27 April. The raid lasted just under ninety minutes, with yet more fires and many bombs. The Assembly Rooms and Regina Hotel were hit, among others, and about 160 people died. The rubble in the streets was knee deep. A woman sheltering asked a little boy “Have you any brothers and sisters?”; he replied, “I did have but they’ve just been killed”. Three soldiers from the Gloucestershire Regiment were fire watching outside the Mary Magdalen Chapel; all three were machine gunned and killed.

The following night people were told to leave Bath for fear of another raid. Thousands left to take cover in the hills and woods. A newspaper described the raids as “Hitler’s attempt to create maximum terror with limited means”. The final casualty list was just over 400 dead, with almost 900 injured, in little more than 24 hours.

Later next day, 27 April, the Luftwaffe moved some of their units to the Netherlands. This enabled them to launch an attack on Norwich that night which lasted almost two hours. Over 162 people died and 600 were wounded. Eric Jarrold, just fifteen at the time and a civil defence messenger, described the noise as terrific; he could see the aircraft as they went over, while the bombs fell at a rate of one per minute.

The next target was York, on the night of 28/29 April. The station was badly damaged, with many casualties, including Elizabeth Simpson, waiting to take a train to Copmanthorpe; she broke both hips and had leg lacerations. There was a direct hit on the Bar Convent that killed five nuns; a survivor, Mother Andrew, wrote a poignant account of her experiences. 110 people died.

The Luftwaffe left York at about 4 am on 29 April; that evening they returned to Norwich for a second attack. 69 people died and many homes and buildings were damaged, including the Norwich Hippodrome, where the stage manager, his wife and two sea lion trainers lost their lives. (Buddy the sea lion survived). There was another attack on the morning of 1 May, which must have been terrifying for the inhabitants; incendiary bombs almost gutted the shopping centre.

Monday 4 May was to become known as the Exeter Blitz. In the early hours of the morning, the Luftwaffe launched a devastating attack, starting with incendiaries and then combining these with high-explosive bombs and machine-gunning. At one point there were over 500 separate fires; many burned for days, and more than 53 firewatchers were killed during the raids. 164 people died, 563 were injured and much of the centre of the city was destroyed. Several people spoke of their firm conviction that the Germans would return the following night to “finish the job”; firewatchers at the Cathedral made contingency plans, while a doctor’s wife drove to Dartmoor to take her sons to safety before returning to the city. She feared she would never see them again.

There was a lull, but at the end of May, the RAF launched a thousand bomber raid on Cologne. Canterbury became the latest target for reprisal raids. On 1st June it was hit by flares, incendiaries and HE bombs; there was considerable fire damage and over fifty died, including a family of eight in Northgate Street. Three further raids occurred during the same week, and people continued trekking out of the town for safety for some time. Gradually, people began to hope the Baedeker raids had finished. However, there was one last attack on Norwich on 27 June, the so-called “fire raid” with over 20,000 incendiaries.

More than 1,000 people died in the raids, and almost 2,700 were injured. Many historic buildings were lost. The Baedeker Blitz would never be forgotten by those who endured it, as the accounts in my book show; these were true terror raids. They are still remembered eighty years on.

The Terror Raids of 1942 is available to order here. You can also purchase an ePub or Kindle edition.