The Sands of Time: A Tale of Two Heinkels…

The Sands of Time: A Tale of Two Heinkels…

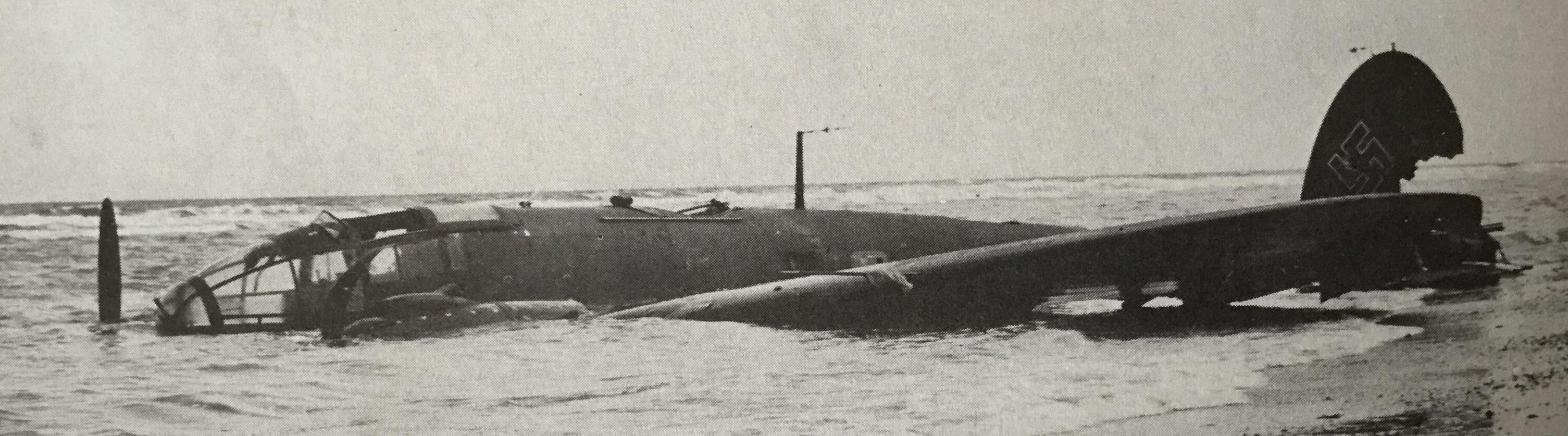

When first I saw the Air Ministry’s 1941 pamphlet on the Battle of Britain, as a child in the 1960s, one photograph therein appeared haunting: the carcass of a shot down Heinkel He 111H-4, partially submerged on a British beach. Many years later I went in search of the story…

After Dunkirk, the Luftwaffe’s new-found access to airfields in the Pas-de-Calais, just over twenty miles across the English Channel from Dover, changed the whole strategic picture. This unexpected geographical shift put the entire British Isles within range of German bombers, which could now be escorted to London by the lethal Me 109 fighter. This unanticipated success was as big a surprise to Hitler as everyone else – the Führer now suddenly presented with an unexpected opportunity to mount a seaborne invasion of southern England. First, though, aerial supremacy, at least over the invasion area, was pre-requisite, and very soon the Battle of Britain would decide the issue. Before assaulting Britain, however, the Luftwaffe needed to re-group and re-fit, so a lull followed the Battle of France and Dunkirk evacuation. By night, though, the Germans maintained a degree of pressure, lone raiders prowling over Britain, dropping bombs and causing a general nuisance. On the night of 18/19 June 1940, the greatest attack to date on mainland Britain was launched, with over seventy intruders attacking a wide range of targets.

That moonlit night, the Luftwaffe was particularly active over East Anglia, with many ‘red’ air raid warnings sounding. Oil installations were bombed at Canvey Island, the breached pipeline blazing for hours, and civilians were killed in Cambridge and Southend. At this time, Britain’s nocturnal defences were totally inadequate, there being no dedicated night-fighting aircraft and Airborne Interception radar had yet to appear. Consequently, day fighters, including the Spitfire, which was not a good night-flying aircraft, were pressed into service to patrol after dark, supplementing the twin-engined Bristol Blenheim equipped squadrons. As a daylight bomber, the Blenheim had proved vulnerable to fighter attack, and the Mk IF version lacked the performance to be an effective day fighter, so instead the latter type provided the backbone of Fighter Command’s nocturnal defence force during this early war period. The night in question would see both Spitfires and Blenheims in action over eastern England.

At 0020 hrs on 19 June 1940, Flight Lieutenant ‘Sailor’ Malan DFC of Rochford’s 74 ‘Tiger’ Squadron scored the Spitfire’s first night victory when he attacked a He 111 of Stab/KG 4 ‘General Wever’, off Foulness, the raider crashing in Chelmsford, ten minutes later. Malan scored again at 0115 hrs, shooting down another KG 4 He 111, which crashed near the Cork night vessel. At the same time, Flying Officer John Petre of Duxford-based 19 Squadron got yet another KG 4 machine – but return fire from the rear-gunner ignited his Spitfire, which literally blew up in his face; Petre survived, but was badly burned. This Heinkel was also attacked by Blenheim pilot Squadron Leader ‘Spike’ O’Brien of Collyweston’s 23 Squadron, whose aircraft went into a spin upon breaking away – unable to regain control, O’Brien ordered ‘abandon ship’, but was the only crew-member to survive a safe parachute descent: Pilot Officer Cuthbert King-Clark baled out but was killed when his body hit the starboard propeller, and Corporal David Little was trapped in the aircraft and killed in the resulting crash. An hour after the Blenheim crashed, 19 Squadron’s Flying Officer Eric Ball also shot down a KG 4 bomber, off Margate.

Over the Norfolk coast, Sergeant Alan Croxton Close of 23 Squadron, flying Blenheim L8687 YP-S, had stalked a He 111 – but was shot down in flames by an alert German gunner. Whilst the twenty-three-year old pilot from Sale, Cheshire, was killed in the resulting crash, his gunner, LAC Laurence Karasek safely baled out. This combat, which vividly lit up the night sky, had not gone unnoticed by Flight Lieutenant Duke-Woolley, also of 23 Squadron, who reported that at 0050 hrs: –

‘Whilst flying at 6,000 feet three miles north-east of Kings Lynn, I observed aircraft subsequently identified as a He 111 held in searchlights at 8,000 feet. Time 0045 hrs. Observed ball of fire which I took to be a Blenheim in flames break away from behind tail of enemy aircraft (E/A). Climbed to engage E/A and attacked from below tail after searchlights were no longer holding. Range 50 yards. E/A returned fire and appeared to throttle back suddenly. Own speed 130 – 140 mph. Estimated E/A slowed to 110 mph. Delivered five attacks. Air gunner (AC Derek Bell) fired several short bursts at varying ranges. After last front gun attack, Air Gunner reported port engine of E/A on fire. Returned to base and landed, starboard engine unserviceable. Several bullet holes in wings and fuselage of own aircraft including hit in starboard wing and fuselage by cannon’.

The enemy raider, a He 111-H4 (fuselage code 5J + DM) of II/KG 4’s staff flight crash-landed in shallow water just offshore at Blakeney Point in Norfolk, a vast expense of flat beach, perfect for a forced-landing. The crew, the Gruppenkommander, Major Dietrich Freiherr von Massenbach, Oberleutnant Ulrich Jordan, Oberfeldwebel Max Leimer and Feldwebel Karl Amberger, swam and waded ashore, covered by auxiliary coastguard men from their nearby station. Sensibly, the Germans surrendered and were taken into custody, confirming having shot down Close’s Blenheim before being despatched by Duke-Woolley and Bell.

It was, in fact, a costly night for KG 4, which lost five He 111s over England. Unusually, Von Massenbach’s Heinkel remained where it crashed off Blakeney Point, remaining in situ, astonishingly, until 1969, when removed on the orders of Trinity House, the charity dedicated to safeguarding shipping and seafarers. In such shallow water, so close to shore, however, it is difficult to understand how the wrecked German bomber was in any shape or form a navigation hazard. The year of its demise also saw, ironically, release of Guy Hamilton’s technicolour and star-studded epic Battle of Britain – which really launched the warbird preservation and aviation archaeology movements. If only, therefore, the Heinkel had survived a few more months, it may still survive, preserved, perhaps, at an appropriate museum. Today, Blakeney Point is owned by the National Trust, which in 2017 reported wreckage from the He 111 being exposed after a storm. Nothing remains to remind us today of that dramatic incident over eighty years ago, but Blakeney Point is certainly an atmospheric place where the imagination can easily visualise that wrecked bomber rotting in the surf.

Moving on, last weekend Sue and I were on the trail of another Heinkel – this time closer to our Gloucestershire home and another interesting story…

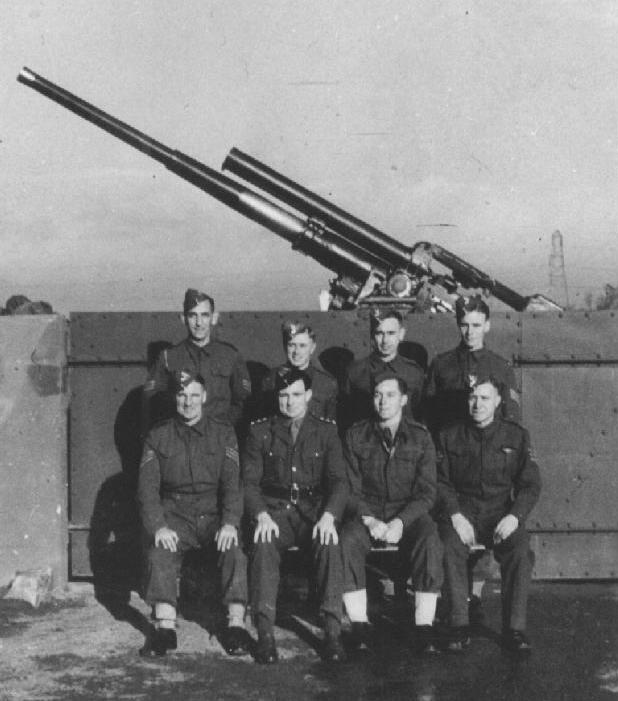

By February 1941, after the Battle of Britain (10 July – 31 October 1940), the German Blitz on British cities was gathering in its terrible intensity. 22 February 1941 dawned a day of low cloud and rain – perfect conditions for lone enemy aircraft to intrude over England in daylight, relying upon cloud cover to reach their targets unmolested. The port of Bristol was already well-known to Luftflotte 3’s bomber crews, and that day 4/KG 27 ‘Boelke’ despatched an He 111H-3 (1G+GM) to attack Avonmouth docks. This aircraft flew just below the thick cloud, at 600 feet, but was out of luck: the 3.7 inch gun crew of B Troop, 236 Battery, 76 Anti-Aircraft Regiment, located at Gordano, near Portbury, just South of Avonmouth, sighted and engaged the raider. The Battery reported that at 1412 hrs: –

‘We saw one of our rounds explode in front of the aircraft which seemed to damage the wing. It staggered on for a bit then hit a balloon cable over Easton Way, knocking a wingtip off. It crashed and exploded at the water’s edge at Portbury, wreckage being strewn over the mud flats. We went to the site and used a 14ft dinghy as a sledge. We got the pilot out who was waist deep in mud and tried to get the other crew member whose parachute had failed. I tugged at the lines but couldn’t haul it in and had to leave him as the tide was coming in. We could see at least two other bodies in the wreckage but had to leave them as well. The flight bag was retrieved from the wreckage , complete with charts and information regarding the target. The pilot made a great point of raising his revolver above his head and throwing it far into the mud, he was quite an arrogant sort of fellow!’

The gunners had captured Leutnant Berndt Rusche.

Feldwebel Alfred Hanke, aged twenty-two, from Furth, Bayern, and Unteroffizier Heinrich de Wall, twenty-five, from Vohsloch bei Ohle, were both killed.

According to Alfred Hanke’s brother, Leonhardt: –

‘Alfred finished secondary school in 1937 and was drafted into the Deutscher Reichsarbeitsdienst (Labour Corps) for six months, after which he wanted to resume his studies at university into aeronautical engineering, hoping to complete this in one go, rather than being interrupted by the mandatory two-year military service. So, he volunteered for the Luftwaffe first, completed his two years, expecting to be discharged in July or August 1939. This was not to be, of course, as no-one was discharged and the start of the Second World War on 1 September 1939 changed the course of Alfred’s life. He then applied for pilot training but failed the medical, so became a navigator instead, training at Kitzingen on the Main river, between Wurzburg and Nurnberg. In 1940, he flew operationally in Belgium and France, his airfield being at Bourges, about 200 km South of Paris’.

Towards the end of 1940, Alfred had gone home to Furth on leave, to join the family celebrating his parents’ silver wedding anniversary. It would be the last time. Leonhardt remembered having a premonition that he would never see his brother again – he was right.

In German aircraft, unlike British and American, the aircraft commander is the navigator, so Feldwebel Alfred Hanke, we can assume, was captain of the ‘Portbury Heinkel’. Two of his crew remain missing to this day: the Bordfunker (radio operator), Feldwebel Georg Jankowiak, a twenty-year old Berliner, and the Bordmechaniker (flight engineer), Gefreiter Erich Steinbach, a twenty-two-year old from Furstgen.

The bomber had crashed on mud flats at Portbury Wharf – a dangerous area, given that the Bristol Channel, or Severn Estuary, has the second highest tidal range in the world. The RAF Intelligence Report on the crashed bomber states that: –

‘Markings: the only letter decipherable was a “B” in black. Crest: an eagle carrying a swastika with letters “KGR” beneath. A plate from the wings was by Arado FW Works… reception date October 1939.

‘Engines: DB601 but no details available as they were practically buried in mud.

‘This aircraft was hit by AA fire… it dived into mud and quicksand and was entirely disintegrated. It was also partly burnt. Portions of six MG 15s (machine-guns) were found… the usual type of bomb gear seems to have been fitted… Crew: four or five, one baled out and is unhurt, and three other bodies were found in the wreckage’.

Which is where it gets interesting…

In the 1970s, and perhaps 1980s, this incredibly dangerous crash site, situated in the Bristol Channel, which has the second highest tide range in the world, was located and visited by local wartime aviation enthusiasts, and in 1989, a recovery licence was issued by the MOD to a now defunct West Country group. No returns form detailing finds was submitted to the Ministry of Defence, however, so it is not known whether anything was recovered, and although one publication reported that items had been ‘recovered from deep mud’, what exactly, or what became of those artefacts, is unknown. Clearly, though, very little of this aircraft was recovered at the time, or indeed since, owing to the nature of the site, the majority of wreckage having long since disappeared deep into the mud and quicksand. There it is likely to remain for all time – forever entombed by the sands of time.

I would like to thank the National Trust for assistance with my research into the ‘Blakeney Point Heinkel’, and especially Allan White for his invaluable contribution to my knowledge of the ‘Portbury Heinkel’; Deborah Morgan at the JCCC, MOD; David Brocklehurst MBE for details of the Kent Battle of Britain Museum’s He 111 restoration project.

Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS

Dilip’s biography of Group Captain ‘Sailor’ Malan, who recorded the Spitfire’s first night victory, mentioned in the text, can be ordered here.

Dilip’s history of 19 Squadron during the Battle of Britain period, including reference to the He 111 destroyed by Flying Officer John Petre, can be ordered here.

Dilip’s recently published Letters From The Few includes a chapter on former KG 4 He 111 pilot Hauptmann Hermann Kell.

Dilip’s website.

Dilip’s YouTube Channel.