The Miners’ Strike 40 years on – Norena Shopland

Women in Mining

Think of mining and you generally think of men. It is a male dominated history.

However, throughout the centuries, millions of women have worked in mining in all fields from underground to pit brows, from cooks to canteens, but mostly notably as background people to men – the wags and mams.

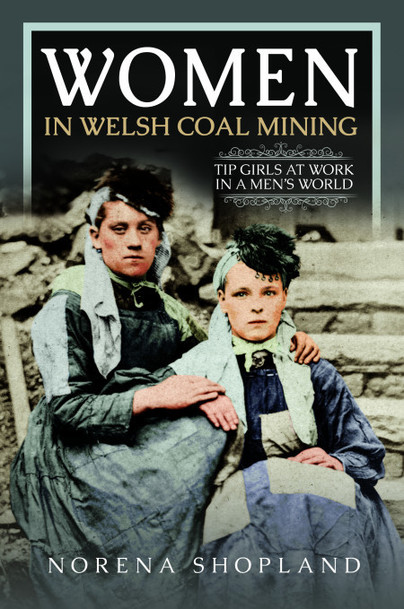

In the late 20th century, some attention was paid to the women working in coal mining, mainly the Pit Brow Lasses of Lancashire and occasionally the Tip Girls of Wales such as Angela V. John’s By the Sweat of their Brow. Otherwise, very little had been written about the Welsh women until my book Women in Welsh Coal Mining: Tip Girls at Work in a Men’s World (2023). Since its publication, it has generated a lot of interest in south Wales and I am constantly being asked to provide talks.

The interest in this book shows there is a desire to learn more about female workers, but sadly women’s history lags a long way behind that of men. Take Wikipedia, for example, of the two million biographies only 19.72% are of women and at the current rate of inclusion, it will take 100+ years to reach equality.

What then, of the nameless women who made up so much of British mining? They are rarely covered in histories appearing only as add-ons – weeping at the mouth of a pit as the mine alarm rings, washing men in tin tubs or caring for children. Where are the begrimed, patch-dressed women wielding hammer and mandrel cleaning and cutting coal? They are part of the ying and yang of coal mining, the men hewed it out and sent it up, the women processed it – but the circle is incomplete and nobody seems to notice.

Read stories of the Pit Brow Lasses and the Tip Girls and you’ll read stories of struggles and hard work, not just physically but in defending their good names as society demanded they stop work and know their place in the home and kitchen. Dirt, equaled immorality in the eyes of the many who could not see. Dirty clothes, dirty faces equaled lesser beings who could be castigated and ordered to work in factories, where none existed, to become domestic servants in areas where the rich were the minority, or stay at home and starve with no income.

Mining is harsh on the body and for those men who suffered disability or death it threw the family into financial hardship. Examine the census records, see how many widows were left alone to raise children. A few lodgers could bring income, but little at that and for families with many daughters sending them to the pits, even when the wages were a fraction of men’s, meant money coming in. And why give that up to starve on the misguided attacks of society which prized clean and compliant women?

Family upon family, saw the mam stay at home with the small children, the disabled men, and the old folks, while the young people went to work; an egalitarian system hampered only by the low wages of the women.

However, mine records will rarely reflect this as women were not recorded as workers, just casuals, and often their money went to a male relative. Shadow workers that were vital to the industry.

That is, until machinery came along and rendered them jobless.

In 1954, the Government banned women working at mines unless in administrative or support roles. In 1979, when the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, which urged laws restricting women’s work hours and some categories of jobs should be repealed, the UK did not let women back in.

The last pit-brow lass in the Lancashire coalfields finished work at Golborne Colliery in 1966 and the last woman colliery-surface worker in the United Kingdom retired in 1972 from the Harrington No 10 mine in Lowca, Cumberland. One of them, Rita Culshaw from Wigan, told the Daily Mirror she had loved the work and, despite being 83, ‘would go back to the mine tomorrow’. It is not known who the last Welsh woman was, but possibly Martha Richards who died aged 93 in 1974, the last woman to have worked in the Stepaside Pits, Pembrokeshire.

Following the Employment Act 1989 women are now allowed to work underground, but few do so.

In 2021 a study was done by Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) and World Resources Institute (WRI) on women working in extractives, those industries extracting raw materials from the earth, and found that 60 countries still have laws on the books that restrict women’s employment in mining, mostly in the sub-Saharan Africa areas. Most of these laws originated from the British Mines and Collieries Act of 1842 that banned women and girls from working underground which spread across the British Empire and elsewhere.

Today, women’s overall participation in the global workforce is 47%, but only 14% of the global industrial mining workforce, and few are in the higher paying jobs being left predominantly in administrate fields. There are women miners, particularly in the USA, and occasionally articles appear about them and their work – but many speak of being hampered by discrimination and the attitudes of men who believe such work is unsuitable for women.

Nothing much has changed then.

You can order Women in Welsh Coal Mining here.