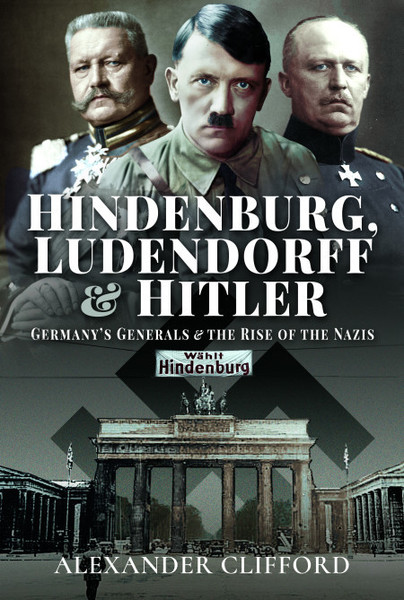

The Field Marshal who put Hitler in power: The postwar career of Paul von Hindenburg

Guest post from author Alexander Clifford.

A ‘good German’, an honourable Prussian solider and the last bulwark against Hitler? – that is how Field Marshal and later president Paul von Hindenburg is often portrayed. But just how accurate is the image of a ‘good’ Hindenburg?

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg was as aristocratic as his name suggested. However, his military career was long if unremarkable. It was only the Great War which rescued Hindenburg from the historical obscurity of retirement. In August 1914, he was recalled as Russia encroached on Germany’s eastern frontiers and, alongside his chief of staff Erich Ludendorff, delivered a stunning victory at Tannenberg in late August which made Hindenburg’s reputation and, given it appeared he had saved the nation from invasion, turned him into the country’s leading war hero overnight.

Hindenburg and Ludendorff formed a ‘happy marriage’, their personalities complimenting each other well: Hindenburg the delegator and frontman with a talent for PR, Ludendorff the temperamental genius. Together they became effective dictators of wartime Germany, dominating not only military affairs but also economic and foreign policy and ousting chancellors who they disliked.

However Hindenburg and Ludendorff failed to deliver German victory in the Great War, even after being given total control over the war effort. The huge gamble of an all-out offensive in spring 1918 backfired and in the summer the German army began to disintegrate. On 28th September, with tears in his eyes, Hindenburg accepted Ludendorff’s view that peace was the only option.

Following the subsequent revolution, armistice and the creation of the so-called Weimar Republic, Hindenburg remained in post as Chief of the General Staff, once again a unifying figurehead. He oversaw the return home of the German army and then the mobilisation of forces to crush communist insurrections. The new government and the army ensured that Hindenburg’s legendary reputation remained untarnished by the catastrophic disaster which he had led Germany into – others would have to be found to take the blame for defeat.

A concerted campaign was underway to distance the Field Marshal from responsibility for the war. These efforts to find a scapegoat for Germany’s defeat would crystalise in 1919 with the Stab-in-the-Back Myth – a conspiracy theory that weak politicians, leftists and Jews were to blame for Germany losing the war and that the army was not only blameless but had never been defeated on the battlefield. For a nation dislocated, confused and traumatised by world war, total defeat, revolution and a deadly pandemic, it was a reassuring myth to tell oneself and it served Hindenburg’s purposes perfectly – he could remain a national hero and dodge all responsibility for Germany’s downfall.

These ideas had been circulating for some time on the fringes of political discourse when Paul von Hindenburg was called, alongside Ludendorff, as a witness to give testimony to the parliamentary enquiry into the defeat in November 1919. Hindenburg’s testimony was explosive. He contemptuously ignored the questions put to him by the panel, and simply read from a prepared statement which exonerated the army and placed all blame on civilians in the government and revolutionaries.

He used a false quote from an English general to prove his point, a piece of fake news that had spread in Germany but Hindenburg now lent it credence. The impact of Hindenburg’s testimony cannot be underestimated. The field marshal was loved and respected, considered a brilliant military leader and the epitome of honour and duty; he was unquestionably the most popular living German at the time. His word carried enormous weight and his message to the German people on the most public stage conceivable was clear: under oath he told them they had been betrayed, that they had been stabbed in the back. What had been a conspiracy theory was, at least for a significant portion of German society, now a statement of fact. Germany’s most respected military figure was lying to his people in order to clear his own name, the cheerleader-in-chief for a dangerous falsehood.

For a time, Hindenburg retired from public life. In 1920 he had been nominated for president but the election had been cancelled because of political instability. In February 1925, the German president died, necessitating an election at last. The right hoped to capture the presidency for its extensive powers, such as the ability to dissolve the Reichstag and promulgate laws by decree using Article 48 of the Weimar constitution. However in the first round of the presidential election, the right’s candidate polled just 38.7% of the vote. As a result, they desperately cast around for a candidate who could win. Hindenburg’s name had been mentioned before, but at 77, he seemed too old for the 7-year term. Nevertheless, the field marshal was approached and eventually convinced. By appearing as the reluctant candidate, called out of retirement to serve his country in its hour of need, Hindenburg was reinforcing his own myth, recalling his return from retirement in 1914.

Hindenburg was hardly the ideal presidential candidate – he declared he would neither travel nor speak. On the other hand of course, he was perfect. He was probably the most famous, and popular, man in the country. He would attract voters from across the political spectrum and especially tempt moderate conservatives and liberals away from the pro-democracy candidate, Wilhelm Marx. The Marx campaign was also hamstrung by Hindenburg’s mythical popularity and refrained from attacking him directly at all. They argued that Hindenburg was unwittingly being used by nefarious political forces and that he would actually rather be left in peaceful retirement. It was not true of course. Hindenburg’s image might be that of a patriotic father of the nation, above party strife but he was right-wing and nationalisitc. It is a testament to the power of the Hindenburg myth that so many believed him to be truly neutral and bipartisan.

Unsurprisingly, Hindenburg won, claiming 14.65 million votes. Many now expected the end of Weimar democracy. However Hindenburg had said during the campaign that he would respect the constitution and he apparently took his oath of office very seriously. There followed a relatively stable period in Weimar history, known as the golden years, in which there was genuine economic prosperity and the standard of living was higher than in even the best Hitler years. A series of centre-right coalitions governed the country and Hindenburg had very little to do with day-to-day politics, instead excelling in the role of a figurehead or ersatzkaiser. He represented the country at home and abroad, appeared on stamps, carried out official ceremonies and worked with authors and film studios to create adorring books, documentaries and dramas about his life. The celebrations of his 80th birthday in 1927 were perhaps the pinnacle of this hero worship, featuring fireworks that drew the president’s iconic head in the sky.

As time went on and the parliamentary system became ever more paralysed, Hindenburg and his inner circle of advisors in the presidential palace had become increasingly involved in the intrigues of Weimar politics. In the spring of 1930, with the Depression underway, Hindenburg appointed Heinrich Brüning chancellor at the head of the so-called ‘Hindenburg Cabinet’ – a right-wing administration of individuals rather than parties that would govern using the authority of the president rather than the Reichstag. Hindenburg and his allies were moving Germany away from democracy and towards some sort of authoritarian system built on the charisma and popularity of the president.

At the same time, the Nazi Party were emerging as a major force in German politics. Hindenburg wanted to invite Hitler and his Nazis to join his nationalistic cabinet but Brüning decided better of it. This meant however that the Hindenburg Cabinet was in an extremely weak position with no parliamentary majority. The administration hobbled through 1931, overwhelmed by the economic blizzard. The president was upset that many right-wing and nationalistic germans appeared to be turning against his government – he was particularly angered that he was routinely hounded and heckled by Nazi brownshirts during his summer holiday in Bavaria and so by the autumn he was determined to prove his rightist credentials. The president met Hitler for the first time in October 1931 but the Führer left a decidedly poor impression on the president and afterwards the Field Marshal reportedly said that the only cabinet post Hitler was suited for was postmaster-general, “so he can lick me from behind – on my stamps!”.

Hindenburg’s term in office was due to expire in spring 1932, with the president now 84. This set up an enticing presidential contest between Field Marshal von Hindenburg and Lance-Corporal Hitler, both of whom attracted huge cults of personality built on their reputations as saviours of Germany. In 1925, Hindenburg had only run because he had the united right behind him against the left and centre. With the exception of the Communists however, all the parties who had opposed Hindenburg in 1925 now supported him, while the nationalist right who had supported Hindenburg in the last election now backed Hitler.

To the president’s great frustration, he failed to win the majority of votes required to win in the first round, attracting 49.6% of the vote. Hitler had 30%. The result of the second round was a foregone conclusion and the president was re-elected with 53.1% of votes cast. Yet Hindenburg was acutely embarrassed by the support he attracted from the centre and left – ‘Reds’ and Catholics were not ‘his people’. The 1932 presidential contest thus left Hindenburg not a triumphant or invigorated leader but instead determined to prove to his critics and lost friends that he was a true nationalist.

Brüning’s days as chancellor were thus numbered, due both to the president’s irritation and the fact his chief advisor, General Kurt von Schleicher, wanted to tame the Nazi Party and incorporate it into the president’s rightist project. Just 6 weeks after delivering the president’s re-election, Brüning was sacked and replaced by a political nobody, Franz von Papen. His cabinet, known as the cabinet of barons, was stuffed with Hindenburg favourites and was made up of aristocrats and civil servants of good nationalist credentials. This was what Hindenburg labelled a cabinet ‘of my friends’ that would surely silence the right wing critics and win the Nazis over.

If only. In a Reichstag election called for July 1932, the Nazis and Communists finished first and third respectively and combined had a parliamentary majority. Although they would never cooperate to form a government they had now had the power to vote down any law, overturn any presidential decree and unseat chancellors to their hearts’ content. Papen’s government was surely doomed and there was also the possibility that a 2/3s majority could be found in the new Reichstag to impeach the president. Hindenburg, Papen and Schleicher found themselves in a trap of their own making. There were 2 stark options facing them: a) bring the Nazis into the government in order to secure a parliamentary majority or b) ignore the election, suspend the reichstag, dispense with the constitution and rule by force.

In August 1932, Hindenburg explored both options. First he met with Hitler and offered him the vice-chancellorship in a famously confrontational interview. Hitler demanded the top job but Hindenburg demurred. Nevertheless, the animosity of this meeting has been overplayed, with Hindenburg finishing by saying to the Nazi leader ‘We two are old comrades and want to remain so. The road ahead may bring us together again. So I extend my hand as a comrade.”

However, German politics remained deadlocked and running out of options, Hindenburg finally offered Hitler the chancellorship in November 1932, on the condition the Nazi leader could build a coalition with a parliamentary majority. Hitler refused, insisting on getting the presidential powers that had been granted to Brüning and Papen to govern by decree. To this Hindenburg himself refused. Papen was ousted as chancellor in favour of Schleicher but no solution to the crisis presented itself.

By mid-January 1933, it was clear that Schleicher too had failed and all he could offer was plan b – a Hindenburg dictatorship of some sort that would require the suppression of the Nazi movement. In the meantime, an embittered von Papen, who was actually now living with Hindenburg, was plotting his comeback. He arranged a series of meetings with the Nazis in which they agreed to form a nationalist coalition with Hitler as chancellor and Papen as his deputy that would include the whole nationalist right. Hindenburg was fully aware of these negotiations and was sold on the idea – finally the right would be united behind him again. However the sticking point was the chancellorship – the president remained reluctant to give it to Hitler and wanted keenly for Papen to return to the post. At some point, exactly when remains murky, the president’s resistance was overcome.

On 30th January 1933, Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor of Germany. It has been widely reported that the president was senile or unwell when he made this decision and there is an apocrahal story that he mistook the marching brownshirts for Russian prisoners of war. However there is no actual evidence that this was the case, indeed although increasingly tired and physically frail, Hindenburg was of sound mind until his final illness in 1934.

The Nazis moved swiftly to consolidate their dictatorship in the first months of 1933. In this, Hindenburg was a willing collaborator. Papen had assumed the Nazis would be easy to control, after all, the real power rested with Hindenburg. But Hitler very rapidly won the president over. He signed the Reichstag Fire Decree that suspended civil liberties without the slightest hesitation. The later Enabling Act diminished Hindenburg’s position by allowing the chancellor to create decrees rather than having to go through the president. However Hindenburg was delighted by the law, happy to be removed from front line politics and no longer, in his words, being a mere ‘signature machine’. At the famous Day of Potsdam, he publicly conferred his mythical reputation on Hitler and the new Nazi regime.

The president had few quibbles with his government’s policies, a rare exception being securing an exemption for Jewish war veterans from the Civil Service laws of April 1933, which banned Jews and political opponents of the Nazis from holding civil service posts. Notably, Hindenburg clearly did not oppose the substance of the law, merely the inclusion of Jewish veterans, insisting that the law was fair, especially as the Nazis had been the victims of injustice from ‘Jewish and Jewish-Marxist quarters’. By late 1933, his declining physical health meant he could play less of a role in public life. He wrote a political will addressed to Hitler that was entirely concerned with the restoration of the monarchy, but Hindenburg left it up to the Führer to choose an appropriate time. Rather, he announced in his public will that Hitler was his successor as head of state, praising the chancellor for putting Germany back on the road to greatness. The president died of lung cancer on 2 August 1934 after an illness of several months.

The sad truth is that Paul von Hindenburg was a German nationalist who had little interest in saving Weimar democracy. He agreed with the Nazis on much more than he disagreed and he had wanted them in his government for years before 1933. He was delighted by the rapid transformation Hitler was able to achieve and so impressed that he regarded him as his natural successor. While unquestionably an election-winner, Hindenburg was not a skilled politician, lacking energy, drive and direction, naturally on account of his age, but he was also inconsistent and unreliable, obstinate on some issues, easily led on others. Despite his popular image as the embodiment of Prussian duty and honour, he abandoned his closest collaborators at crucial moments. He was also vain and always anxious to protect his standing with ‘his people’. After 1930, he was determined to create a rightist government that would incorporate the far-right, regardless of the will of his own electors. The appointment of Hitler marked the realisation of this goal and, after January 1933, Hindenburg largely acted as if the mission had been accomplished. He was a statesman who willingly handed power to criminals, demagogues and thugs.

You can order a copy of Hindenburg, Ludendorff & Hitler here.