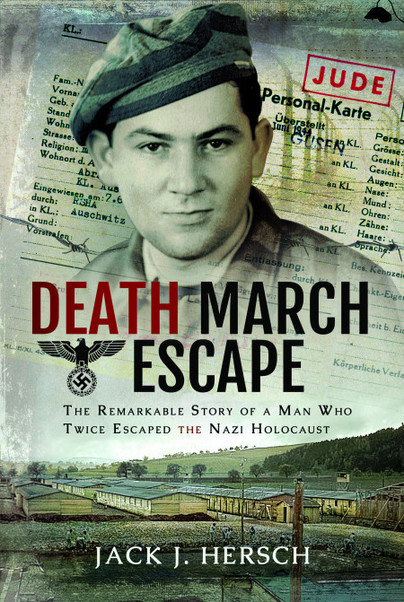

Meet the author: Jack Hersch

Today we have an exclusive interview with Pen and Sword author Jack Hersch. Jack’s book, Death March Escape is out now. Read on to discover more about the incredible true story behind the book.

1. What made you decide to write your father’s story?

I wrote it because of

how people reacted when they’d hear me tell the story. Every year,

my father would tell his story of survival and escape on the Jewish

holiday of Passover. It is a tradition at the Passover evening meal

to recount the story of the Jews leaving Egypt three thousand years

ago. My father would always digress during that telling to relate his

own story of escaping twice from the Nazis. So I knew the story well,

and often told it to others. But one of my tellings, in late 2015,

stood out from all the rest. For some reason I no longer recall, the

story came up during a business dinner. Afterwards, one man at my

table came up to me and said that he had never met a holocaust

survivor, he had never even met anyone related to a survivor, and had

never heard a story like the one I had just told. He said it changed

his perspective and outlook on life. Nothing, he said, would ever be

overwhelming to him again, because my father’s story put his own

life into perspective. I realized then, that there must be thousands,

and maybe even millions, of people who would be similarly impacted if

they knew my father’s story. And so that same day I decided to try

to write it.

2. Can you

describe the moment you found your father’s photograph on

the Mauthausen Memorial’s website?

My first reaction to

seeing my father’s picture on the Mauthausen Memorial website (the

site for Mauthausen Concentration Camp) was complete shock. First, I

had never seen this photo before. I have a few photos of my father

from his youth, taken before he’d been sent to concentration camp,

but not this one. Second, the picture was a crystal clear close-up –

a headshot – that showed my father’s 17-year old face with such

clarity, it seemed it had been taken a week ago. Third, in the photo

he looked nearly identical to my teenaged son. Besides shock, I felt

intensely curious, as the caption under the photo said my father had

been rescued from a death march by Barbara and Ignaz Friedmann, and

hidden until American forces liberated their town. How, I wondered,

did the concentration camp know about the Friedmanns? And, again, how

did they get that photo!?

3. What was your

next step (after finding the photograph)?

I clicked on the

“contact us” section in the Mauthausen website’s menu, and

wrote something to the effect of, “I’m his son. How did you get

this picture, and how do you know this story?” I also offered to

provide information about my father, starting with the fact that the

escape they wrote about was his second escape – he’d

escaped once before and been recaptured. That started a dialogue with

Mauthausen historians and eventually led to my visiting the

concentration camp.

4. What was your

research process like? You eventually flew over to Europe and the

concentration camp – what was your starting point and why?

I actually began my

research on the internet from my home in the US. Though it seems now

like an obvious step in the process, the idea of flying to Europe

hadn’t yet entered my mind. I can’t explain why that was: my

father nearly died in this concentration camp, he escaped twice from

death marches leading out of this camp, and yet I had no desire to

visit it. The drive to go there only came after research on the

internet, and email conversations with Mauthausen historians,

continually uncovered new facts about my father’s time in

concentration camp, until it became abundantly clear that not

visiting would be a gigantic mistake. My starting point for that trip

was Mauthausen Concentration Camp, in western Austria, which is now a

memorial and museum restored to its original dastardly condition. I

also visited the home of the Friedmanns, the people who rescued and

hid my father after his second escape, in Enns, Austria. They are no

longer alive, but the tenant there allowed me freedom to walk around.

And I walked parts of the death march route, in a successful attempt

to discover precisely where my father’s two escapes took place. I

chronicle all these visits in my book.

5. You were

already familiar with your father’s story; did you make any

further unexpected discoveries on your journey?

I

made many unexpected discoveries as I walked around the concentration

camp where he slaved, walked the death march route, and met with

historians and experts in their homes. I learned, for instance, that

one evening when SS soldiers at the concentration camp offered my

father and his group of prisoners all the soup they could eat, this

was not an example of humane treatment, as I’d always believed.

Rather, it was murder. The SS knew eating too much would kill a man

who’d been underfed for a year or more, and that my father and his

fellow prisoners would be unable to resist the offer of unlimited

soup. The SS hoped they would all eat too much and die. Somehow my

father knew the dangers of over-eating, and had only one extra

helping. But two-thirds of the 150 prisoners with him that evening

lacked my father’s self-control, and were dead by morning.

6. If you could

ask your father two questions today, what would they be?

My father went back to

visit Mauthausen in the late 1990s, and never told me. I learned

about that trip from my aunt, his sister. So first, I’d like to

have asked him why he never told me he’d returned to Mauthausen.

Second, I’d like to know what kept him going as he slaved day after

day, moving heavy granite rocks around the granite mine that was

attached to the concentration camp. I’d like to know what got him

out of bed, gave him the strength to work in the mine regardless of

the weather, enabled him to keep going all day in spite of being fed

next to nothing, and then do it again the next day. I never asked him

that. He never explained why – as he dwindled from 160lbs to 80lbs

and contracted tuberculosis, typhus and pneumonia – he didn’t

simply succumb to the pain and hunger, and allow himself to die.

7. Do you feel

you have completed your research, or is there yet more of the

story to uncover?

My research is

essentially complete. There are times in the book when I take

educated guesses based on facts, and I walk readers through my

thought process in the hope they will agree with my assessments. But

going from guess, to fact is probably never going to

happen, because my father is no longer alive to answer any questions,

and I’ve already met with as many people as possible to take

uncertainty out of my research. Yet I still hope that I might meet

someone one day who says, “I read you book, and my father told me

about…” and that story will turn a guess into a fact.

Beyond that, there’s not much more that I will be able to learn

about my father’s time in concentration camp, and his escapes, that

I didn’t tell the reader.

8. If you were to

describe your father in 5 words, what would they be?

I think the five best

words to describe my father are: strong, resilient, resourceful,

upbeat, gutsy.

9. Your father’s

story is truly remarkable, but which part of it stands out most for

you – which part inspires you the most?

This is a particularly

difficult question. So much of his story is incredible and inspiring

to me. But one part stands out. It’s when my father made the snap

decision to escape the first time. In that first escape, he was

heading west on a forced march, what we now call a death march.

There were around 1,000 Jews with him on that march, closely guarded

by SS storm troopers. Six miles after leaving Mauthausen they reached

a major intersection. My father and his fellow marchers were heading

west, while crossing directly in front of them, heading north, were

thousands of Austrian refugees fleeing the fighting. As my father

stepped into the junction, the SS guards stopped his fellow marchers

immediately behind him, so the refugees could go once my father

cleared the intersection. But the refugees couldn’t contain

themselves, and they plunged into the crossroads before my father

reached the far side. He suddenly realized he was caught up among the

Austrians. He now had a choice. He could march a few more feet and be

clear of the intersection and back with his fellow prisoners. Or he

could turn 90 degrees to the right and pretend to be part of the

refugee crowd. He must have realized the impossible odds against him

blending in with the refugees: he was wearing a concentration camp

uniform, he was emaciated, and he was exhausted. But he made the turn

anyway. He took two steps and spied a raincoat on the ground. He

quickly scooped it up and put it on. It fit well enough. And no one

said a word to him. Maybe no one noticed? Maybe people noticed but

were too caught up in their own attempts to survive to bother saying

anything? I truly don’t know. And it doesn’t matter: my father

made the instantaneous decision to turn with the flow of refugees,

and it worked. He was free, at least for a few minutes. When I

travelled to Austria and stood in the middle of that intersection

picturing myself as one of the Jewish death marchers, I was so

physically staggered by the sheer guts it took for my father to make

that turn, I couldn’t breathe. The motto of the British Army’s

SAS, the Special Air Services commando unit, is: Who Dares Wins.

My father dared, and won. I have no idea where he got the nerve to

make that turn. But he wanted to survive, and so he made the

turn, he took on that dare. That turn is, to me, the

single most inspiring thing my father did during the war.

10. You were

recently honoured with the Spirit of Anne Frank Human Writes Award.

How did that make you feel?:

I felt tremendously honoured. My father’s story, and stories of others who survived the barbarity of the Nazi regime, need to be told, retold, and told yet again. We – the human race – must be reminded of how terribly we can treat each other when we forget our basic humanity. I feel a deep pride that my book contributes to that effort of telling and reminding. If, in the end, one single person who reads my book veers away from bigotry and cruelty, the effort to tell my father’s story will have been worth it. And the award acknowledges that.

Death March Escape is available to order now from Pen and Sword.