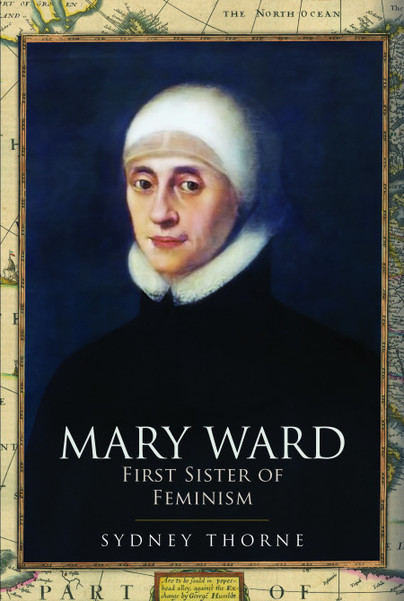

Mary Ward, First Sister of Feminism

Guest post from author Sydney Thorne.

Mary who?

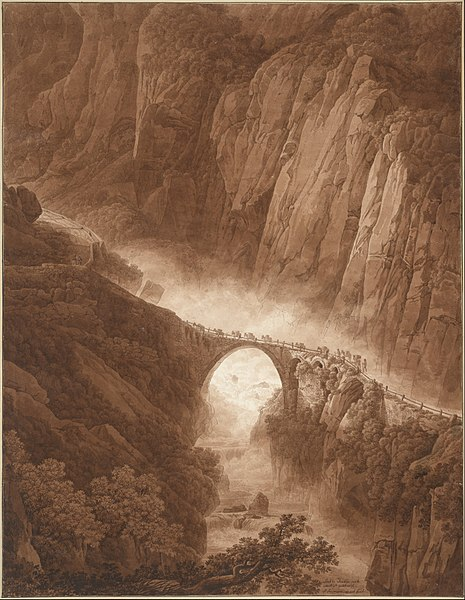

Just over four hundred years ago – in October 1621 – a Yorkshire woman called Mary Ward set off on a long walk from Brussels to Rome. She walked across a Europe in the throes of the Thirty Years’ War, made her way over the Alps in winter and completed her epic 1500 mile journey in only eight weeks.

It was unusual for a woman to undertake such a journey in the early seventeenth century. But Mary’s reason for travelling was if anything even more extraordinary than the journey itself. Her aim was to persuade one of the most powerful men in Europe, the pope, to grant her, a woman, some of the rights and freedoms enjoyed by men. It was rare indeed for a woman to seek an audience with the pope, rarer still for a petitioner of either sex to challenge the pope on a point of doctrine. But Mary Ward was confident of her case. She had chutzpah.

What moved Mary Ward was a passion that is surprisingly modern: she was appalled by the almost total absence of girls’ schools. Within the previous century the Jesuits had established schools for boys across Europe and as far afield as Persia, Florida, Brazil and Japan, and Mary’s idea was simple: if the Jesuits could achieve this for boys, she would do the same for girls. But if a network of girls’ schools was to be set up across Europe, then women must be given the freedom of action to achieve this – which meant that Mary and her women teachers must enjoy the same freedom of organisation as the Jesuit teachers. Hence her journey to Rome to see the pope.

Mary certainly had experience of fighting against the system. Born into an English Catholic family a few years before the Spanish Armada, and thwarted by the anti-Catholic penal laws, Mary Ward slipped out of the country and, within a few years, set up four girls’ schools in four different European cities. They were among Europe’s first ever free schools for girls. Back home in England, meanwhile, where Catholic schools were illegal, Mary established a secret network of women who went about in disguise and taught girls within their own homes.

What did Mary teach her girls? Sure, there was reading, arithmetic and needlework, as we may expect, but also Latin, modern languages and drama, subjects which were traditionally reserved for boys. In an age when female roles in Elizabethan Theatre were still taken by men, this makes Mary Ward one of the first recorded people to put English girls on stage. And over and above setting up the schools themselves, Mary had to recruit women with the ability to teach in the schools and organise their training – there was no existing system she could tap into. Not bad for a woman who was only 36 years old.

As a loyal Catholic, Mary adhered to the time-honoured Christian tradition of organising her teachers as a religious order of nuns. The trouble was, the Catholic Church did not accord nuns the same rights and freedoms as monks. Nuns were subject to strict enclosure. That is to say, they were forbidden to go out into society and obliged, instead, to spend their whole lives enclosed within the walls of their convent. There were no exceptions – not to teach, not even to look after the sick. These restrictions derived from the prevailing view that women were weaker creatures, prone to sin and incapable of taking responsibility for themselves.

Mary Ward strove with all her being against this negative, defeatist view of women. ‘There is no such difference between men and women that women may not do great things,’ she asserted. It was a remarkably bold claim in the early seventeenth century. What Mary Ward saw very clearly was that the problem lay not with women, but in the restrictions put upon them. That was the reason for her walk across Europe to petition the pope. Mary sought a dispensation from enclosure for herself and her teachers, a dispensation that would kickstart the effective teaching of girls. It did not seem much to ask.

But the men in Rome had no intention of loosening the rules that gave them a grip on the lives of women. To begin with, they played for time. Then, when it became clear that Mary would not back down, all the force of the Vatican was brought down on her – muck-raking rumours, interception of letters, school closures, hearings before the Inquisition, orders restricting her freedom of movement, a papal bull, excommunication, prison. These men were ruthless. They were the very cardinals who, two years later, would force Galileo to recant. Would Mary do the same?

No she would not. Instead, she countered the men in Rome with trust, love, and – here’s the surprising one – good humour. Her reaction when a priest thanked God he was not a woman because, said he, women cannot understand God? ‘I answered nothing,’ said she, ‘but only smiled.’ And paraphrasing St Paul’s famous line about faith, hope and love she wrote, ‘In our calling, a cheerful mind, a good understanding, and a great desire after virtue are necessary, but of all three a cheerful mind is the most so.’ A cheerful mind rated higher than a great desire after virtue! It’s a rare motto in the seventeenth century, and it makes Mary Ward appealingly human, ordinary and modern.

Proof that a victory of sorts was won in the end is that Mary Ward schools exist today in some thirty-eight countries. Mother Teresa was a Mary Ward sister before she founded her own order. Africa’s first female Nobel Peace Prize winner, Professor Wangari Maathai, was a student at a Mary Ward school in Kenya.

The poignant fact remains, however, that had Mary Ward been allowed to achieve her dream back in the early seventeenth century, the benefits of education for humankind – male and female – would have come so much earlier.

Follow the story of this fascinating woman across seventeenth century Europe in ‘Mary Ward – First Sister of Feminism’ by Sydney Thorne, published by Pen and Sword.