Author Guest Post: John Paul Davis

The Worcestershire village of Inkberrow differs little from many other English rural settlements. Believed to be the inspiration for Ambridge – the fictional setting of The Archers – the area boasts many of the usual charms. The picturesque Old Bull pub – similarly named to The Bull in Ambridge – remains the heartbeat of the local community and a common stop-off place for locals and walkers.

In the Middle Ages, the community lay within the bounds of Feckenham Forest – a favourite among the Plantagenet royals. Three miles to the east, the Cistercian nunnery of Cookhill complemented the local church, which remains at the heart of the parish. Across the road from St Peter’s, a modern boardwalk surrounding a rectangular area of thick overgrowth circled by water is popular among dog walkers. Besides a brief note on an information board that the water is designated ‘moat’, nothing is mentioned of the site’s significance. It is challenging to accept that this isolated area of raised banks, trees and shrubbery where squirrels roam leisurely was once a castle.

Like many lost castles, the story of Inkberrow’s disappeared fortress is an obscure one. Records confirm John Marshal obtained the manor from the Bishop of Hereford in the mid-1170s, after which a timber structure was constructed. On John’s death, the estate passed to his famous brother, William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke.

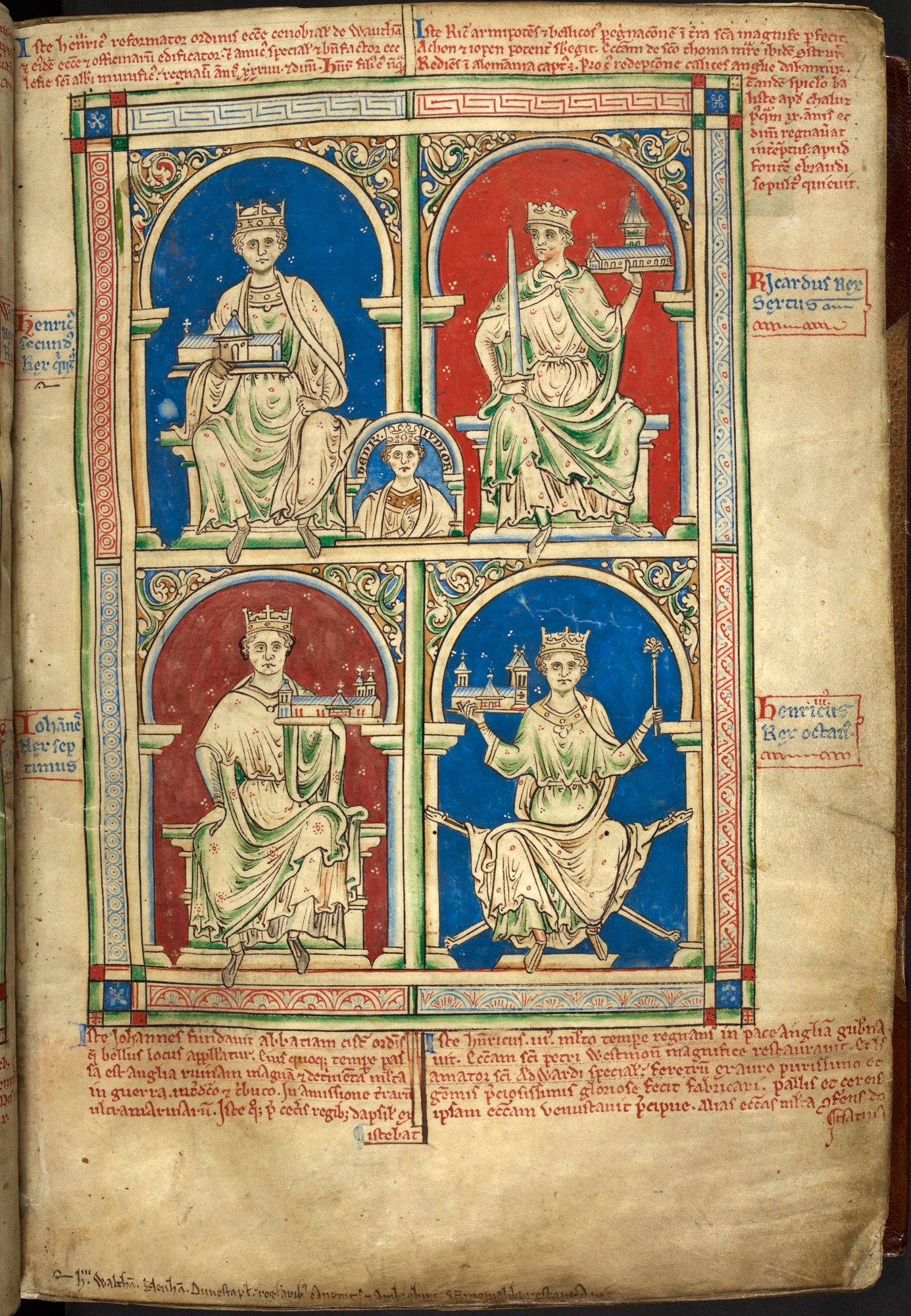

William’s contributions to English history are, of course, famously celebrated. A minor son of a minor lord whose ancestor was made Marshal of England by Henry I, William served no less than five kings, including Henry the Young King, who had been crowned joint king alongside his father. Ten years after Richard the Lionheart had granted William the hand of Isabel de Clare, the de facto heiress to the great de Clare fortune, John formally made William the earl of Pembroke. When he died in 1219, his properties, including Inkberrow, passed to his eldest son and namesake. After the sudden death of the second earl in 1231, the late regent’s estate entered the possession of his second son, Richard, henceforth 3rd Earl of Pembroke.

Even in the context of England’s long history, Richard Marshal stands as a unique figure. A man of many attributes, including horsemanship, warcraft, swordplay, artistic taste, wit and intelligence, Richard was very much his father’s son. Like the great regent, his reputation had been built on the continent, having been the beneficiary of the family lands in Normandy. Henry III’s reluctant agreement for Richard to maintain the ancestral lands, which William the Younger had signed away to him in June 1220, along with the recently vacated earldom, evoked the grumblings of the magnates. Further to the usual criticisms regarding the empowerment of outsiders, the holding of property in England, Wales, and Normandy brought an added complication. Since Philip II had conquered Normandy in 1204, Richard was technically required to offer homage to two kings.

When Richard returned to England to formally take possession of his late brother’s estate in 1231, he found a government in crisis. Fourteen years of relative peace had allowed the young king’s chief advisors to take a firm grip on the reins of government; however, many problems from John’s reign remained unresolved. Worse still, the exchequer was reeling from a combination of troubles with Llywelyn ap Iorwerth and a recent failed attempt to reclaim the Angevin Empire, which Richard had supported. When Henry’s charges gathered in Brittany in May 1230, Richard’s hometown of Dinan was the meeting point.

Blame for recent failures fell firmly at the door of Henry’s justiciar, Hubert de Burgh, 1st Earl of Kent. A capable bureaucrat who had served John loyally, Hubert had experienced both enduring love and bitter hatred in England. The hero of the Battle of Sandwich in 1217 following his stubborn defence of Dover Castle, both of which helped ensure victory in the First Barons’ War, Hubert was less popular among the magnates. Already on thin ice with Henry since being forced to delay the recent invasion due to insufficient resources, Hubert came increasingly under fire for his possessive influence. When Henry gave in and sacked Hubert in 1232, sentencing him to imprisonment in the dungeons of Devizes Castle, the king reappointed Peter des Roches, Bishop of Winchester, as his chief advisor.

The bishop’s appointment would have a lasting impact on England’s history, including Inkberrow’s. Briefly justiciar under John, and Henry’s tutor until around 1221, des Roches was a controversial figure in England. No friend of Hubert, the pair had, nevertheless, worked constructively between 1217 and 1223. Prior to this, he also excelled during the First Barons’ War, notably his inspired performance during the Fair of Lincoln in 1217.

These achievements, however, failed to win him supporters among the baronage. Of particular concern was his willingness to fill key positions with inexperienced foreigners and his enrichment of personal favourites to the detriment of Englishmen. Richard Marshal’s close ally Gilbert Basset, whose father had served John and Henry loyally, was one of many to lose out. When the king reneged on his royal grant of a manor in Wiltshire in favour of des Roches’s favourite Peter de Maulay, Marshal took up Basset’s grievances personally.

The scene was set for civil war. When Marshal, fearing capture, failed three times to attend councils in the summer of 1233, Henry’s government imposed sanctions. Further to the forced temporary surrender of his castle at Usk, the king ordered that his manors, including Inkberrow, be dismantled. Despite the setback, Richard and his comrades proved formidable opponents. Successful in spiriting Hubert de Burgh from captivity, Marshal’s taking of Monmouth Castle when outnumbered ten to one and wrecking carnage on the lands of the royalist supporters caused the king and des Roches countless headaches throughout the year.

Fortunately for the people of England and Wales, the strange conflict recalled by the chroniclers as the ‘Marshal War’ was soon confined to ignominy. Roundly embarrassed by the great regent’s son, Henry sought reconciliation and sacked his close advisors, vowing instead to rule as his own chief minister. As the 20th-century historian Sir Maurice Powicke rightly commented, Henry had learned a great lesson in kingship.

Sadly for Marshal, there would be no happy ending. A pre-existing des Roches’ plot ensured his death in Ireland. As the Annals of Waverley sorely lamented, ‘England weep for thy Marshal . . . because on thy behalf, England sought to love’. Though Richard’s properties and titles passed to his brother, Gilbert – henceforth 4th Earl of Pembroke – the castle at Inkberrow was never rebuilt. A fortified manor may have been erected on the site, yet what became of it is now unknown. Like the fate of its final owner, the castle has become invisible except to those who know where to look. Should one do so, the reward will be the discovery of a rare legacy of England’s forgotten civil war. A land once owned by earls, now ruled by squirrels.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

King John, Henry III and England’s Lost Civil War and Castles of England by John Paul Davis were published in July and September 2021, respectively. Both are available on Amazon or direct from Pen & Sword History.

John Paul Davis is the international bestselling author of eleven thriller novels and six works of nonfiction. Several of his books have been bestsellers, including The Templar Agenda (UK Top 20) and The Cortés Trilogy (US Top 20 and UK Top 40). His works of nonfiction have been the subject of international attention, including articles in the Sunday Telegraph, reviews in the Birmingham Post and Medieval History Journal, and mentions in USA Today, The Daily Mail and The Independent. His biography of Guy Fawkes, Pity for the Guy, was featured on ITV’s The Alan Titchmarsh Show in 2011. His first nonfiction for Pen & Sword, A Hidden History of the Tower of London – England’s Most Notorious Prisoners, has also been a bestseller in the US.

He was educated at Loughborough University and lives in Warwickshire. If he’s not writing, reading, or visiting medieval ruins, he’s probably practising martial arts or hiking.

www.instagram.com/officiallyjpd