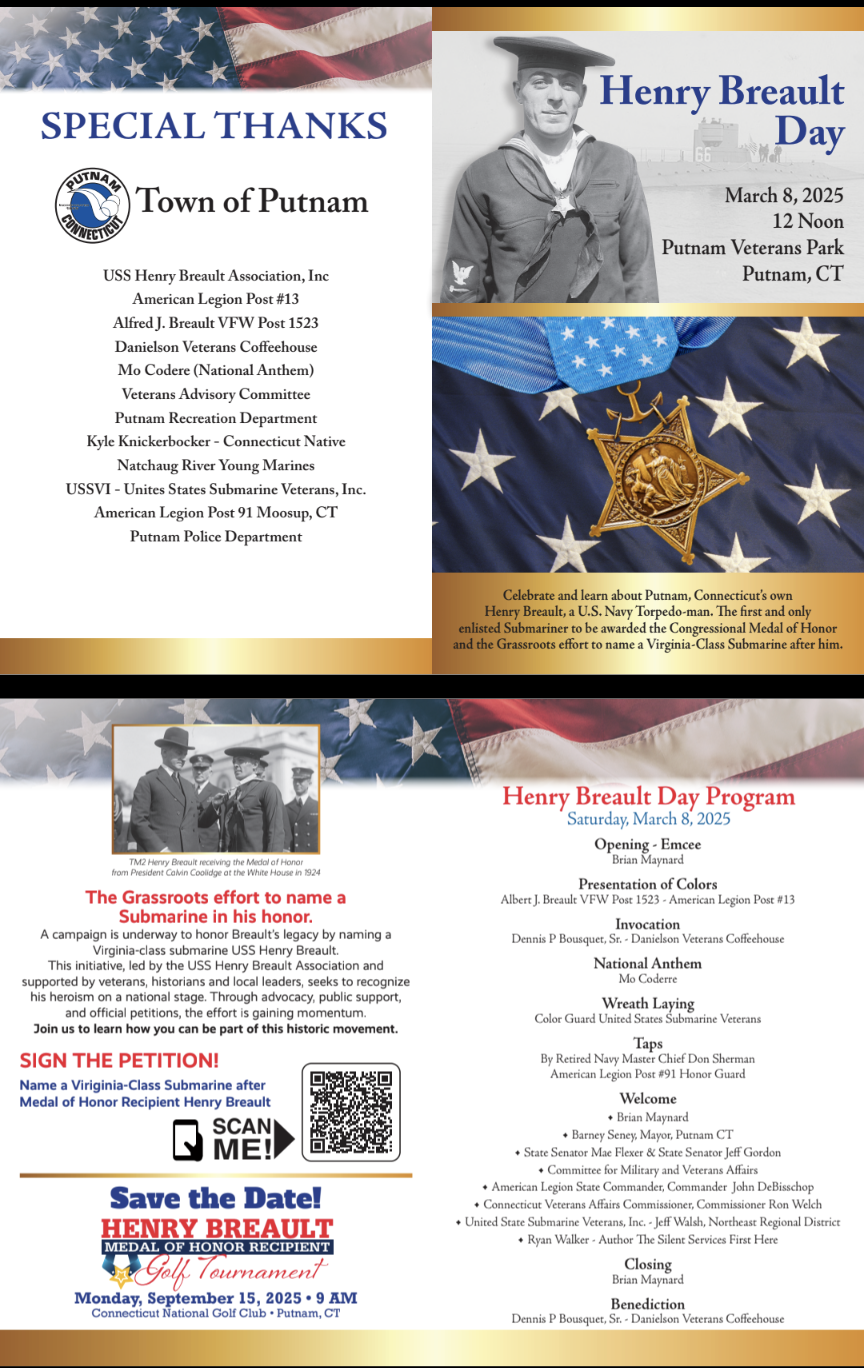

Henry Breault Day, March 8, 2025

Guest post from Ryan C. Walker.

I was driving to Putnam after a hectic week when the snow started falling lightly. It wasn’t enough to accumulate, but it wasn’t in the forecast either. The weather was supposed to be relatively warm and sunny—perfect for an outdoor event in late-winter Connecticut. But of course, on March 8, 2025, the day of the first annual Henry Breault Day, it was cold and gusting.

I’m not exaggerating when I say it was a busy week. I worked my usual job, attended a medical appointment, went to my United States Submarine Veterans Incorporated meeting at the Groton Base, participated in the Naval Order of the United States meeting in Newport, RI, attended a 4:30 AM Ph.D. seminar, then had a 7:00 PM meeting for my Adjunct Professor role. On top of that, I did an interview for Mike Allen’s Amazing Tales Podcast and ended the week with a book signing at the Submarine Force Library and Museum. I barely had a moment to breathe, but the most important event was today: in his hometown of Putnam, CT, on the 101st anniversary of the award ceremony for the first submariner to receive the Medal of Honor, a new town holiday would be announced.

Henry Breault was a first-generation French-Canadian, born to Joseph and Flora Breault on October 14, 1900. He served in both the Royal Navy Canadian Volunteer Reserve (1917-18) and the United States Navy (1920-41). On October 28, 1923, Breault was aboard the USS O-5 when it collided with the United Fruit Company’s Abangarez. His Medal of Honor Citation reads:

“For heroism and devotion to duty while serving on board the U.S. submarine O-5 at the time of the sinking of that vessel. On the morning of October 28, 1923, the O-5 collided with the steamship Abangarez and sank in less than a minute. When the collision occurred, Breault was in the torpedo room. Upon reaching the hatch, he saw that the boat was rapidly sinking. Instead of jumping overboard to save his own life, he returned to the torpedo room to rescue a shipmate who he knew was trapped in the boat, closing the torpedo room hatch on himself. Breault and Brown remained trapped in this compartment until rescued by the salvage party 31 hours later.”

Surprisingly, there’s little evidence suggesting Breault had agency in telling his own story. No official statements were recorded in his Military Personnel File, and only one letter from him was found—its publication in the New York Times is the reason we have it today. The letter reads:

“Just a line to let you know that I am still alive. You have no doubt read about the sinking of the submarine. We were down there for hours and had no food. There was water in the lead tanks, but we did not dare to use it because it had been there for months and we were afraid of lead poisoning. I sure was a sick boy, but am well now. I have been out helping to raise the submarine. She is all right except for the central control room where she was struck. The craft will soon be in condition again. But some of the crew will never go down in a submarine again. Fortunately, it did not bother me at all.”

The primary account of the rescue, however, belongs to the other sailor Breault rescued—Electrician’s Mate Chief Petty Officer Lawrence Brown. While Breault was sent to a depressurization chamber to treat Caisson disease, Brown stayed behind to recount the story to the United Press Association. His account was then reprinted by other newspapers. Julius Grigore summarizes this well, using Brown’s perspective of the ordeal.

Brown explained that he had been resting before his watch when the Abangarez collided with the O-5. Despite feeling the hit, he stayed in bed until Breault woke him up. “We both went into the torpedo room, closing the door behind us. The boat sank in thirty seconds, settling in forty feet of water at an angle of 70 degrees to starboard.” It’s surprising that Brown didn’t hear any communications, but the only known order was heard from Captain Card of the Abangarez just before the collision, possibly given verbally from the bridge. Since Brown was asleep, it’s likely he didn’t hear the order to abandon ship.

Trapped in a compartment with twelve inches of water and only a flashlight to see by, Brown recalled, “the first hour was the hardest.” After 45 minutes, the O-5’s batteries caught fire, making the heat unbearable. With no food or potable water, they remained optimistic that they could survive for 48 hours and that a crane would lift them before then. After three hours, it became clear that efforts were underway to rescue them. The pair split up: Breault moved as far aft as he could, while Brown moved forward with a hammer to bang on the hull, signalling that they were still alive. Brown recalled, “Breault played with the hammer to indicate we were in good shape.”

The first attempt to rescue them came around the 12-hour mark. Although it failed, it helped to level the boat, making it easier to move and more comfortable for the trapped men. By the third attempt, Brown said the last 20 minutes were “terrible,” and Breault estimated the pressure at between 25-50 lbs. Although the doctors treating him disputed these numbers, they agreed that the pressure was high. When the ship finally broke the surface, workers rushed to open a hatch. “Then we heard the water splashing over the top, and our comrades walking on the deck, and we knew we were up. Breault opened the hatch, and the light was so bright I could not find my way up.”

According to the reporter, Brown “seemed no worse for wear” and was lucid enough to retell the story. Brown’s account became the primary one by chance, as he was the only one conscious enough to respond to inquiries. His decision to focus the spotlight on Breault was a sign of true leadership—he gave Breault the praise he deserved without any self-aggrandizement. Brown should serve as an inspiration to all Navy Chiefs.

Breault’s commanding officer, LT Harrison Avery, likely heard this account and soon recommended Breault for the Navy Cross. Later, Admiral Montgomery M. Taylor and Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby upgraded the award to the Medal of Honor. Breault received the prestigious honour on March 8, 1924, 101 years ago, on the White House lawns from President Calvin Coolidge.

Henry Breault Day

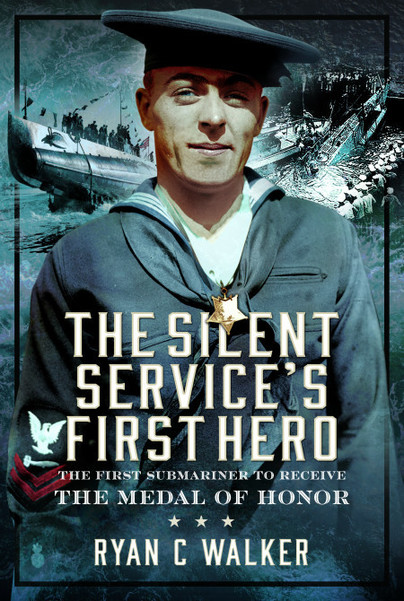

Brian Maynard of American Legion Post 13 spearheaded the movement to get Putnam to recognize Henry Breault, the subject of The Silent Service’s First Hero. Last year, during the centennial celebration, tributes included naming the Henry Breault Basic Enlisted Submarine School Graduation after him and reading Vermont House Concurrent Resolution 167 in Montpelier. This year, Breault’s hometown was ready to declare March 8 an official town holiday. The Putnam Town-Crier effectively conveyed the events (many of the passages will come from this paper), and a video by local station WINY was livestreamed on Facebook to over 15,000 viewers.

Emcee and veteran Brian Maynard noted that the community “comes together time and time again to find ways to honour those who gave great service to our country.”

Mayor Barney Seney read the proclamation designating March 8 as Henry Breault Day. He added, “We want to make sure his name and his service are not forgotten.”

State Senator Jeff Gordon praised Breault’s heroism, saying: “When I learned more about what Henry Breault did—rushing into that sunken submarine… he didn’t have to do it, but he put his life in danger to save a fellow submariner. He did it because he knew about service; he knew about loyalty. He knew about faith. In the end, it worked out well for them. But that is an incredible legacy.” Gordon also called on citizens to thank veterans every day and to ask what they can do to help them and their families.

State Senator Mae Flexer expressed hope that Henry Breault Day would provide an opportunity for the community to reflect on Breault’s life, service, and the lives he saved.

State dignitaries also spoke. John DeBisschop, American Legion state commander, spoke about bravery, teamwork, and sacrifice. He emphasized how Breault’s actions were an extreme example of how servicemen and women go above and beyond for their brothers and sisters in arms. Connecticut Veterans Affairs Commissioner Ron Welch highlighted Breault’s “extraordinary courage on October 28, 1923,” and spoke about the department’s efforts to provide services to veterans in eastern Connecticut. Jeff Walsh of the United States Submarine Veterans Inc. Northeast Regional District also called on the Navy to name one of its Virginia-class submarines after Breault.

As the keynote speaker, I had the privilege of addressing the crowd, who braved the cold and wind to remember a hero. People from Vermont, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Maine, Massachusetts, West Virginia, and across Connecticut gathered to honour Breault and the lovely town of Putnam. They stood in the cold for over an hour to ensure that a hero would be remembered. I will never forget acknowledging the efforts of so many, including close friends and family members.

Thanks to Brian Maynard and Mayor Barney Seney, Henry Breault’s legacy will never be forgotten in Putnam. That first crowd will remember the importance of that day and laugh whenever anyone mentions how cold that day was; but say they were damned proud to be in the audience. Thank you. I conducted a book signing at the VFW, where it was a bit warmer, and paid my respects to Breault’s grave in St. Mary’s Cemetery, still lovingly maintained.

Further Listening, Reading and Viewing:

Sign the Petition Here

Order your copy here.