From Goddess to Witch

Guest post from Alexis Prescott.

The word “witch” is often associated with the female, derived from the old English ‘wicca’, meaning sorceress and from the Germanic ‘wichelen’ which meant the ability to bewitch. For the Jacobeans, the witch was a hideous, haggard, decrepit woman who sold her soul to the devil for the purposes of performing unnatural acts upon the environment and mankind. But where did these beliefs originate? My investigation into the depths of Greek and Roman literature, found an evolutionary development of how the haggard witch came to be: from her divine, benevolent origins to eldritch witch extraordinaire.

The Greek Witch: Hecate and Circe

Greek writers generally perceived witches to be pharmarkides (witches that dealt with potions) and rhizotomoi (witches that were ‘root-cutters’, who dealt with herbs). Both Hecate and Circe were divine beings who possessed such herbal knowledge. Hecate, though, had many attributes: she was associated with magic and witchcraft, had knowledge of the moon, doorways and thresholds, and the underworld. In an animalistic way, she was connected with creatures of the night and barking hellhounds. In fact, she was often given dogs or puppies as sacrifices, as well as offerings of illuminated cakes, as one of her key symbols were burning torches. There are two distinct representations of her in art form. One is of a single-faced goddess and the other, which is more recognisable, is of a three-faced female.

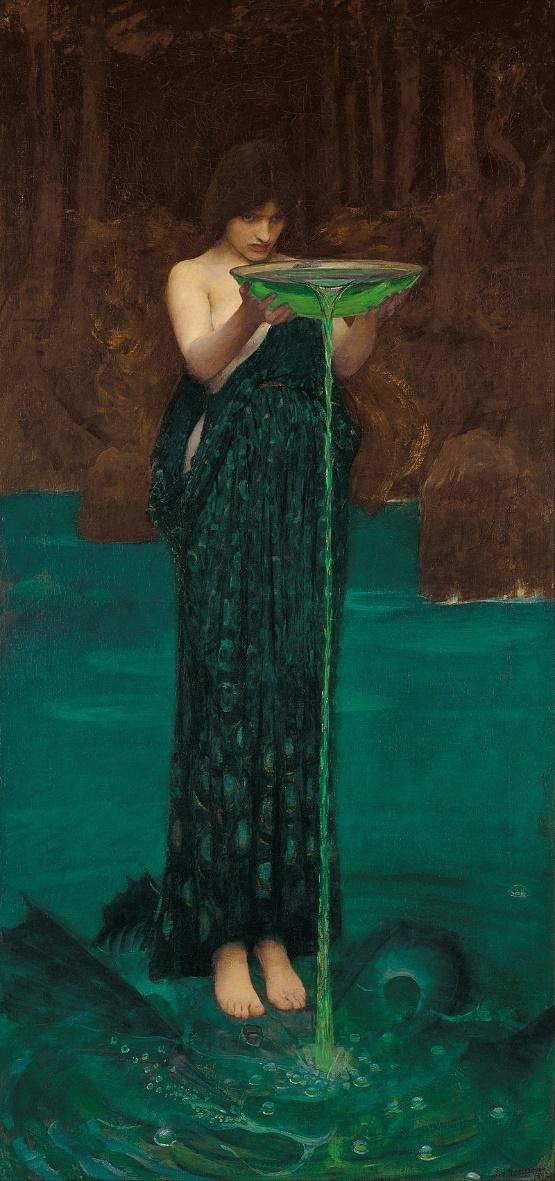

Hecate originally surfaced as an apotropaic entity, protecting the thresholds associated with life and death but in the 5th Century BC, she became increasingly linked to spells, curses, darkness, daemones and disembodied souls, even becoming the patroness of witches. As a result of this vilification, Hecate was seen as an emblem of dark witchcraft with her appearance famously marred in Shakespeare’s Macbeth where she encourages the three withered hags to concoct a potion containing unsavoury items such as tongues, legs and livers. Circe, similarly, is portrayed initially as a beneficial deity, dedicated to aiding the long lost, home-sick hero Odysseus. As a benefactor, she is the perfect guide for Odysseus, advising him to take a journey to the depths of Hades which serves as a pivotal moment within the Homeric epic enabling Odysseus to explore his own katabasis. Her benignity however, like that of Hecate, is eroded a few centuries after the oral tradition of the Homeric epics, with Circe later becoming a powerful witch whose knowledge of curses and spell making leads to catastrophe, as portrayed grotesquely by the Roman poet Ovid in his Metamorphoses, when his malevolent Circe transforms the beautiful nymph Scylla into a monster that grows barking hell hounds from her abdomen that can gobble up unforeseen sailors deep at sea.

The Roman Witch: Erictho

The delight in portraying witches as nefarious and immoral became a favourite pastime for Roman writers, particularly in the 1st century BC and AD. We have, for instance, the witch Erictho who takes centre stage in Lucan’s Civil War, an epic focusing upon the civil war between Julius Caesar and Pompey. As the war reaches its crescendo, Pompey’s son, Sextus, seeks out the witch Erictho in desperate need of a prophecy. He finds a witch that dwells among graves in a dark cave, loitering in the boundary between life and death. Her appearance is filthy, ugly, unkempt and generally disgusting, combined with matted hair. She emerges before Sextus from the threshold of death only when the earth is shrouded in black storms. Most of her vile offences concern souls, dead bodies and infants. She has the power to bury good souls still trapped in their bodies when fate still owes them years and she can perform necromancy seamlessly and enjoys ripping away the marrow from a rotting body, as well as digging out its eyes and nails, this she does through the action of gnawing. Sometimes she waits to snatch innards from the thirsty jaws of wolves. The prophecy she provides Sextus is a deadly one that predicts the deaths of both Pompey and his bloodline. The episode reads like a proto-gothic horror scene, leaving you trembling and fearing the capabilities of haggish women that dare to linger on the periphery of society. This is the general portrayal of Roman witches. They have lost all divine and beneficial mannerisms and have become the wicked witch in the woods that we are all familiar with.

Why did the witch become the hag?

The haggish, evil entity of the witch enters Roman narration from the 1st century BC and is seen as a common stock character from the 1st century AD. This was a period of great social change within Roman society, with many men adopting a strict corporal ideology. They had an innate fear of effeminacy, mollitia, and any form of emasculation. This they believed would occur as a result of allowing women to dominate their bodies and thus reduce their roles within society. The insertion of the hag witch within literature demonstrated the dire consequences of allowing women to take control and dominate – it rendered the man impotent. This impotency could be quite literal. For example, the witches in Apuleius’ Golden Ass threaten castration. The hag witch encouraged men to reclaim their masculine traits and to ensure women were kept firmly in their place. Thus, this stock character reigned supreme within literature enabling misogyny to prevail beyond the fall of the Roman Empire, warning men of the wrongdoings of women that dared to take control and act as an inversion to the subservient female. With the rise of the feminist movement in the 20th Century, we see a move towards reimagining the misogynistic portrayal of women in literature, such as in the recent rendering of Circe by Madeleine Miller. However, the nightmarish hag still has a lasting stronghold in modern times, found within the horror film spectacle or the fantasy miniseries, reminding us of how the witch serves as a symbol of instilling misogynistic values upon women through the process of creating undesirable, frightening, and in this instance, female antagonists.

The First Witches is available to preorder here.