Fighting with Pride: Lieutenant Commander Craig Jones MBE Part 3

We hope you enjoying our Fighting with Pride blog series. Today we have the final part of Craig Jones chapter, The Unsinkable.

Fighting with Pride is out now.

HMS Fearless was the grand old lady of the Fleet and at one time, command ship for land operations in the Falklands War, she had earned a place in the affections of thousands of servicemen and women across four decades. I was to join the ship as she ploughed her way up the Channel, bringing her deployment-weary crew ever closer to excited families and Christmas leave in her home port of Portsmouth.

Fearless had been on an exercise with a NATO Task Force for a few weeks and her return via the Channel provided an opportunity for me to have a couple of nights at sea with my fellow officers before taking over my new role. As soon as the ship was alongside in Portsmouth, the crew would scatter to all corners of the UK, and I wanted to get to know them – and for them to get to know me – as quickly as possible. Change was coming and time was running out for me.

Joining by a long helicopter ride in winter was not my preferred mode of transport, but after years of serving in aircraft carriers, I had become accustomed to the noisy, cold, draughty and somewhat uncomfortable experience. For the pilot and observer (navigator), there was a window to look out of, ear guards in a well-fitting safety helmet and a comfortable seat. However, in the back of the cab there was an air of austerity about this mode of travel.

The Royal Naval Air Station at Culdrose in Cornwall was the nearest landing site to the ship’s planned route so I grabbed a hire car and headed down, with just a couple of olive green holdalls containing the basics of uniform and toiletries. There was something distinctly unmilitary about civvy suitcases and I had no wish to step onto the flight deck of my new ship trailing a Samsonite roller and looking like cabin crew. The officers’ mess at Culdrose was home to 814 Squadron, ‘The Flying Tigers’, and 849 Squadron, with its airborne early warning capability, who spent much of their time embarked in the aircraft carriers. I was very much a ‘carrier queen’, a curious bit of naval slang for those of us who availed of the comforts of our larger aircraft carriers. The mess was busy with pilots and aircrew enjoying a last few days together before returning to their families for Christmas leave, and there were lots of familiar faces. It was a rule of thumb that after five years service, you could walk into a wardroom anywhere in the Fleet and sit down for a beer with somebody you had served with. I was then in my eleventh year of service and knew that my evening would be spent remembering past deployments and visits to ports in far-flung parts of the world, and I joined a group of young aircrew with whom I had served in the Gulf in 1997. They had completed their last day of flying before Christmas and were loud and raucous, sat amidst a range of drinks that looked like somebody had raided a minibar. As I finished my second gin and tonic, I remembered a past two-hour helicopter flight to Bari in Italy on the morning after a Trafalgar Night Mess Dinner (the Royal Navy’s annual commemoration of the death of Lord Nelson), and the thought of rattling around in a helicopter with a hangover again didn’t appeal. So I turned in early amidst a barrage of raucous banter.

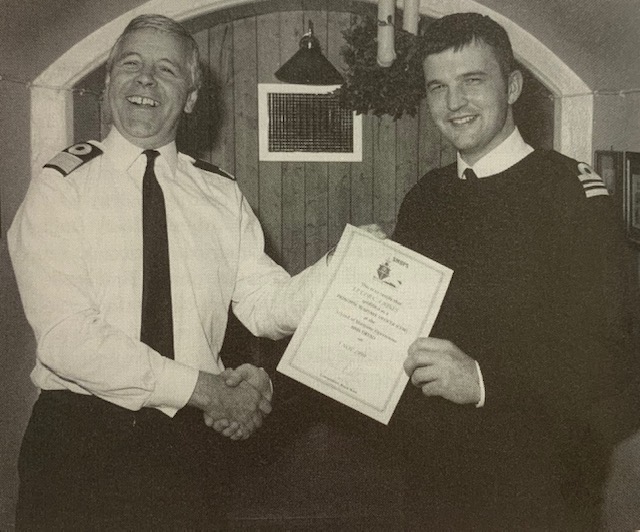

Passing out of the Maritime Warfare School as a ‘Principal Warfare Officer’ a few months after the vetting interview.

The following morning, I found myself in the crew room, looking out across the airfield at the grey Sea King helicopter that would take me to the ship. The sliding door was slammed shut behind me and I looked out across the apron towards the crew room. It looked inviting and I couldn’t help but wonder if it might have been easier to meet my colleagues in Portsmouth!

I had always looked forward to joining a new ship, but this time was very different: life was about to change; there was no turning back. It was Wednesday, 8 December 1999, and two days before, while packing my holdalls, I had received the call from Angela Mason, Executive Director of Stonewall – the gay and lesbian equality charity. Stonewall had been fighting the gay ban for a decade and I’d kept in touch, always using telephone boxes or lines that could not be traced before checking in. By then I had high level security clearance and had completed specialised training in signal intelligence gathering at GCHQ. I knew the risks of secure and insecure telephone lines and I had been extremely cautious over the years. As soon as I heard Angela’s voice I knew what would follow: ‘It’s over, Craig,’ she said, ‘they’re making an announcement early in the new year, in Parliament.’ I had planned for this moment for many years, but the longer I served, the clearer it became that the services would struggle with this begrudged change and my first thoughts of a joyous day had given way over the years to an acceptance that I would simply exchange one complicated life for another.

12 January 2000: It was a little after 4.00 pm when the Right Honourable Geoff Hoon, Secretary of State for Defence, stood up to address the Commons. It had already been a long day and after lunch in the wardroom I had walked onto the upper deck to clear my head. The seamen were out painting the ship, a task that was never quite completed. I was still a new face, and I introduced myself to a number of the men and women who were working ‘up top’ on this crisp and cold January day. Most had been home for Christmas leave, which made for easy conversation, and those who hadn’t got home were eagerly looking forward to their break. I quipped the adage ‘Second leave is best’ with those who were yet to get away. After an hour or so, I returned to my cabin and slid shut the nearly 40-year-old metal door. In my cabin there was a sturdy wood-framed bunk, which folded back by day to provide a bench seat. Beside it there was a writing desk with shelves above and retaining

straps to keep my warfare manuals and reference books in place in rough weather or at war. There was a wardrobe that was little more than torso high and closing the door needed both hands and the toe of my boot, ideally while listing to starboard so the suits swung away from the door. On my desk there was a large green blotter and a signal pad, upon which I wrote a wide range of classified ‘signals’ in an age before secure email found its place at sea. My bunk was folded back and had three broad leather straps to keep me in my bed in the worst of hurricanes. Tucked down the side there was a ‘buggery board’, which slotted into the middle of the bunk to brace against in the roughest sea states. Its name always reminded me of the spirit and humour in the unique language of the Royal Navy and Royal Marines, a language that needs translating to family and friends for decades after completing your service. In my case, the buggery board saw little action because in a real storm I was always on the bridge. I had an iron stomach in the heaviest of blows and was always excited by a tumultuous sea. Driving a warship was the privilege of my life and I loved the seamanship challenge of keeping the ship steady in storm conditions. Learning the technicalities of the missile systems, gunnery and sonars needed to work in the operations room had been a struggle, but on the bridge of a ship I was in my element and I had an instinctive knowledge of the art of ‘sea keeping’. I was always popular with our chefs, who faced the daily challenge of cooking three square meals a day (four in wartime) in heavy seas. Too fast running down the waves risked a broach, where the ship suddenly veered to be beam on to the rolling waves. In the worst cases, warships had rolled 70 degrees when knocked down by towering waves. Too slow and we risked being pooped (overrun by the towering waves). Fearless had a dock gate and an aircraft hangar at her stern, so pooping could cause very serious damage to our ability to launch and recover our Royal Marine Landing Craft or to the multi-million pound aircraft.

I was to take over the role of Operations Officer from Lieutenant Commander Peter Sparkes when he completed his tour later that month. Peter was a terrific officer, blessed with good humour and a gangly but athletic stature. He was also a gifted warfare officer, skilled at driving and fighting ships, and was highly respected and universally well liked. Our paths first crossed on our Officer of the Watch Course, where we learned our trade of driving warships in the gentlemanly countryside setting of HMS Mercury, in the stunningly beautiful Meon Valley in Hampshire. I was forever grateful to Peter for his help and encouragement to pass my Battle Fitness Test, a prerequisite of being able to continue the course. Peter recognised that I was a reluctant and unenthusiastic runner and he virtually pushed me around the course and over the line. It is these moments of camaraderie, teamwork and friendship in peacetime that form the bonds upon which we rely in war. Peter was an officer I would wish to go to war with, if we had to, and I was pleased and reassured to have him around in January 2000.

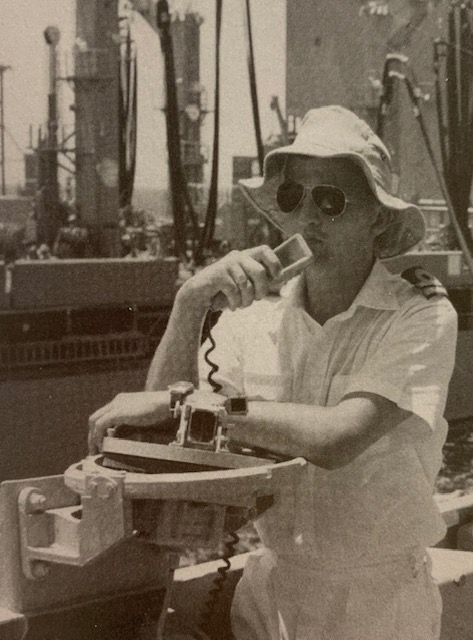

Driving from compass platform during replenishment at sea, one of the most hazardous evolutions a warship ever undertakes.

Peter had handed his cabin over to me early. It was larger and had extra seating space for meetings associated with my new role. Taking over as Head of Operations so soon after completing my year-long Principal Warfare Course was daunting. Fearless was a ‘snake’s wedding’ of systems, bringing together a unique mix of a handful of modern self-defence capabilities with engineering, propulsion and domestic services systems that belonged in a museum. The weapons and marine engineering teams faced the daily challenge of keeping the old girl going by integrating systems that on any ordinary day were either incompatible or broken.

13 January 2000, 1552 hrs: In the corner of my cabin above my desk was a loudspeaker, thickly coated with almost forty years worth of paint. Below the speaker was a Lego-style Bakelite volume switch and a tarnished brass on/off toggle. I sat on my bunk, flicked the toggle and cranked the switch around to hear the broadcast live from Parliament. The speaker crackled into life and I came in in mid-sentence to hear Jack Straw answering awkward questions about the ailing General Pinochet’s convalescence in London. I flicked my cabin light off, to be alone in the dark with the crackly speaker and my thoughts. The continued presence of General Pinochet was an embarrassment and Mr Straw was no doubt pleased to give way to his fellow cabinet minister, the Secretary of State for Defence. Geoff Hoon stood up to begin a speech I had waited a very long time to hear, but the pause as Straw sat down and Hoon stood made me think that Hoon had been in no rush.

The greater part of Hoon’s short speech focused upon the fact that the change of policy he was to announce was born of necessity, following a European Court of Human Rights ruling in September of the previous year. Lustig-Prean vs United Kingdom established that the ban on gay men and women serving in the UK Armed Forces was a breach of Article 8 of the Treaty of Maastricht, which identified the right to a private life. It was important that the case had been won; however, it was not a foregone conclusion that the UK would lift the ban, and there had been a long and difficult wait for news. The court’s technical focus upon the link between the ruling and the concept of what defined a private life had left me wondering for some months if the UK would adopt a policy that copied the US ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ policy. This policy, brought in by Bill Clinton as a compromise position, had resulted in more gay men and women being dismissed than the total ban that preceded it. Thankfully, the Ministry of Defence had no wish to be dragged through another decade of unwinnable court cases and they adopted the Australian model of a ‘Code of Social Conduct’, defining the way in which sailors, soldiers and airmen and women should respect each other. It was simple common sense; however, the prevalence of the word ‘private’ early in his speech made me fearful of a policy that ‘Dare Not Speak Its Name’.

Hoon may have found comfort when in the presence of senior officers by the government being compelled to implement change, but to me it lacked moral courage. His speech had an air of apology and I winced and grimaced with each turn of phrase. He continued pressing his point, repeating the court’s technical statement that sexual orientation was a ‘private matter’. This was to be at the heart of the Armed Forces’ way of managing what was seen as a highly challenging change. This was, of course, a policy born in a storm, an outcome of years of battle by the services’ most senior officers. I often wondered if that time and effort could have been better used petitioning for improvements to the equipment desperately needed by our front-line troops throughout the 1990s. Was it naive or wrong to hope for a triumphant statement heralding great change? Naive or not, Hoon made a rueful and begrudged statement and I couldn’t help but think that he had examined all other options over a period of months before rising to his feet in the Commons that day.

He continued:

Implementing the changes successfully will be a challenge for leadership at all levels of the Armed Forces, but such challenges are not new and all three Services will be equal to the task. With the commitment which is in place from the very highest levels of the chain of command, I am confident that our Armed Forces will adapt to the change in the professional manner for which they are rightly held in the very highest regard. There will be those who would have preferred to continue to exclude homosexuals, but the law is the law. We cannot choose the decisions we implement. The status quo is simply not an option. The code of social conduct centres on the paramount need to maintain the operational effectiveness of the Armed Forces. I have no doubt it is the best way forward.

My cabin was dimly lit, but still I sat at my desk, head in my hands to shut out the little light that prevailed. Were we really to announce a policy that bridged a gaping hole in the Armed Forces Covenant by saying that ‘the law is the law and you cannot pick and choose’? Did we honestly believe that managing the continued service of our remarkable gay servicemen and women would be challenging? I was angry. Very angry.

The speech ended and other MPs rose to their feet to speak. A debate continued and I zoned in and out. Ian Duncan Smith clearly lamented the change and there seemed sympathy in his tone with Geoff Hoon’s depiction of a Hobson’s choice. There were considerate and closed-minded statements and questions from across the political divide, none of which mattered. With some relief, I listened to a comment by Gerald Kaufman MP:

Over the years, indeed centuries, homosexuals have served at every level in our Armed Forces with loyalty and distinction. Is it not better, therefore, to accept that fact than pretend it does not exist? It will not do for people to say that they oppose discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in principle when they act differently in practice.

This went to the very heart of the matter for me. I was appalled by the breach of the Armed Forces Covenant and to this day, feel that a profound apology by those in uniform who presided over this denigration of the fundamental duty of officers has been missing. The covenant is a ‘promise’ made by the government and those who have power and influence over our Armed Forces that those who serve or have served, and their families, are treated fairly. It is not a new concept and has existed in one form or another for over 400 years. A great deal of work was done after 2000 to define the covenant, notably by General Sir Richard Dannatt, later Chief of the General Staff of the Army. In the last few years of my career I drew my sword repeatedly against General Dannatt and his staff. However, I note with great respect that he believed that the men and women of the Armed Forces were deserving of the corporate protection of our most senior officers. My only criticism would be that for a few years, he left some of those men and women behind because they were gay. Nevertheless, this honourable officer, with a strong Christian faith, earned my admiration and trust for unexpectedly doubling back, a matter I shall return to. As he stood up to speak, Geoff Hoon knew beyond question that thousands of serving gay men and women would hear his words. These stoic folk were already doing their ordinary duty in their ships, regiments and squadrons across the world, despite being corporately unwelcome for every day of their service leading to this day and for many days to come. The Ministry of Defence’s treatment of these men and women had been shameful and the recalcitrance in Hoon’s words and tone of his speech was not bringing those days to an end; it was continuing the hurt.

A run ashore in Turkey with officers, their wives and Adam, 2001.

For a few moments, in my darkness, I felt lonely. There were of course people in society that had at the heart of their beliefs a clear understanding of the fact that it was nonsense to expect our Armed Forces to protect the ordinary freedoms that we had then denied them. But in January 2000, there was a prevailing majority view in Whitehall, and specifically in the Ministry of Defence, that hounding gay men and women out of the services had been in the country’s best interests, and if they had been able to ‘pick and choose’, as Mr Hoon suggested, they would have done so.

My thoughts drifted to what the coming weeks would bring; some of this I knew, some could not be known. When I tuned back in to the parliamentary broadcast, Tam Dalyell, the MP for Linlithgow, was lamenting that he had attended a debate about Serbia earlier that afternoon in Westminster Hall and that the hall was stuffy, smelly and airless, and he compared the odour to a rather full school pupils’ changing room. I rose to my feet and clicked the loudspeaker switch one turn to the left; that was enough of that. I grabbed my mobile phone and left my cabin, bound for the upper deck. It was time to call Matthew.

If there was one comfort on that day, it lay in the consistency of my viewpoint over the years of my service. My world and the service were converging, but the pace was always too slow for me. From the very beginnings of my time in the Royal Navy, I had found it very odd that an organisation at the heart of protecting our peace and freedoms should so irrationally accept a business case for a policy of exclusion that had more holes than a colander. My mind drifted back to where it all began … with Michael Ball.

13 February 2000, 1800 hrs, Wardroom, HMS Fearless: The best I can say of my commanding officer in HMS Fearless would be that our views on the repeal of the gay ban were at variance. For me, the lifting of the ban was a blessed relief from living half my life in the shadows. It brought me back into the military family and restored my integrity, something fundamental to the service of an

officer. My new commanding officer lamented being let down by ‘the mandarins in Whitehall’. The year ahead would have its lively moments and I was never far from controversy. I came out in my commanding officer’s cabin, to stem what I saw as a denigration of the ordinary responsibility of officers to lead. Whether or not the change in policy was liked, it was our shared duty to implement it. This was the first opportunity for the covenant to be recognised for this beleaguered group and I was determined that the men and women in my ship would detect no hint of chagrin in the announcement that was to be made to them ahead of Geoff Hoon’s speech to the Commons. My tactic worked and my commanding officer gave a deadpan address to the ship’s company a few hours ahead of the formal announcement. But my stance set us up for an uneasy relationship, and I suspect we were both happy to part company early in the following year as I moved to a new role at HMS Collingwood.

What was truly remarkable about my time in HMS Fearless was that with each day that passed, the welcome of my ship’s company grew warm and for the first time in my life, I truly felt part of the team. People work better when they can be themselves. Adam and I had waited a long time for the ban to be lifted and no moment was to be wasted. When the notice went up for a wardroom ball at the Queen’s Hotel in Portsmouth to celebrate Burns Night on Saturday, 29 January, less than three weeks after the ban was lifted, I signed my name on the list and placed Adam’s in the partner’s box alongside it. What followed was a mix of delight from close colleagues and tangible panic from a small group of senior officers led by the Captain that seemed to focus upon whether Adam and I would dance together. I found this quite bizarre. As an officer, the dignity of the uniform is paramount, and never more so than in the company of partners. The idea of Adam and I dancing around the floor in some sort of ‘gliding embrace’ was a truly ridiculous notion, but it reflected the concern of a small cohort of officers across the service who perhaps considered notions such as whether gay officers might incorporate feather boas into their uniform to add a hint of pizzazz. I have often said that if held to the light, my watermark and defining characteristic is ‘Royal Navy’ and not ‘gay’, and I believe many of my brethren see the world similarly. It is our loyalty to the service that defines us.

Conscious that eyes would be upon Adam far more than on me, it was time to visit Gieves & Hawkes. From their base at No. 1 Savile Row, since 1771, ‘Gieves’ has won the affection of generations of Royal Navy officers for a classic English style that is instantly recognisable and has dressed kings and princes. No green bow ties or crimson cummerbunds, or shirts fit for Charles Aznavour’s wardrobe; just simple, elegant gentlemen’s clothes. They did their job, but I have to say that walking into the Queen’s Hotel as the first gay partner to attend a formal function with a serving officer took raw courage and a great deal of dignity. Adam’s dance card kept him busy all evening and if I’d wanted to take his hand in the ceilidh, I’d have had to join the queue. At a time when most officers didn’t know what a gay partner looked like, Adam looked reassuringly like them. Not all courage is that of the battlefield.

In the years the followed, I continued to find my place in the service but was constantly aware of the difficulties being faced by other LGBTQ service personnel. By 2001, I was the Vice-Chair of the newly formed Armed Forces Lesbian and Gay Association and involved with an unduly reserved initiative by the personnel directorates to engage with LGBTQ personnel. Bullying, harassment and, in some cases, assault were far too common occurrences and there had been no effort at all to overturn the climate impact of a thirty-year strongly defended gay ban. My petitioning for change fell on deaf ears and I became increasingly angry that conservative attitudes from senior officers were setting the pace of change to the detriment of some of our most vulnerable personnel. In consequence, I undertook a range of initiatives to address an inclusive policy ‘that dare not speak its name’. These were not welcome interventions and I found myself commonly at loggerheads with very senior officers who had a habit of writing to me, signing in the traditional green ink, to tell me how disappointed they were at having to admonish me (because I’d been vocal about the plight of gay colleagues or paid scant attention to Queen’s Regulations and written directly to the Minister for the Armed Forces or the Secretary of State for Defence). In one exchange it was reported to me that a senior officer had said it was perfectly ordinary and no issue to be gay. I sent him an impertinent email and invited him to go to his local paper shop and buy a copy of Gay Times and post it to me though the internal mail system, if it were true that we lived in such a utopian society. I called his executive assistant a week later to be told that the Commodore had ‘given it a go’ without succeeding, and that the point had been well made. In June 2005, I snuck in through the back door of the Second Sea Lord’s Diversity Conference, an event that welcomed over 100 captains of industry for presentations and a Q&A session. At the end, when the Q&A started, with the Royal Navy’s head of personnel (Second Sea Lord) on stage, I asked why this prestigious event had passed with discussions about race, faith, ethnicity, gender, disability … indeed, every protected characteristic other than sexual orientation. The question won me another letter signed in green ink!

I have no idea about the role of luck in my life or whether the likes of Quentin Crisp or Oscar Wilde have sat on a cloud sprinkling fairy dust where it’s most needed. However, there have been a handful of occasions when the turn of events has pulled me, bedraggled, from the lion’s mouth.

With my latest green ink signed letter still smarting, I put my best uniform on and set off on the Saturday following the diversity conference to Trooping the Colour. Adam and I had won tickets in a lottery for military personnel, and it was a welcome distraction. Adam had kitted himself with morning dress for the occasion and I have to say, we looked quite dapper, but the air for me hung heavy with what had become all too regular clashes with service chiefs regarding their lack of positive message about their LGBTQ servicemen and women. But I dusted myself down for the occasion and we took our seats. In the course of the event I caught up with Lieutenant Polly McCowen, a logistics officer whom I had taught navigation in HMS Fearless. She was with her parents, who I remembered had some sort of association with the Civil Service. At the end of the pageantry they kindly hosted us for lunch at Leith’s and during the discussions, my disappointment at the Armed Forces’ lack of initiative for its LGBTQ community poured out. Polly’s father was a distinguished man who I was later to establish was the Cabinet Secretary to the Thatcher government, Lord Armstrong of Ilminster, and perhaps one of the most important political figures of the second half of the twentieth century. Lady Armstrong sensed Polly’s disquiet at my situation and by the end of the lunch it was evident that there was compassion for my invidious position.

A few days later, an invitation dropped onto our doormat that was to provide the breakthrough I had been unable to find in my petitioning of captains, commodores, vice admirals, generals, air marshals and ministers. The invite was to a private gathering at Leeds Castle, two nights over a weekend, when opera was being performed in the grounds for a wider audience. We arrived in our clapped-out Rover 216 to a scene reminiscent of Upstairs Downstairs, as staff whisked away our luggage (and our car even faster). The first meal was to be lunch and we changed to ‘dog robbers’ (naval slang for jacket and tie). As we left our room in one of the castle’s turrets, we turned a corner and found ourselves face to face with First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Alan West and Lady West. A little startled, I introduced myself by military rank and turned to introduce my boyfriend ‘Adam’. Slightly mischievously, I accentuated the ‘boy’ bit, but without necessity; Lady West was brimming with delight at the encounter and I saw little more of Adam that weekend!

Over those fateful couple of days, I had the chance, in those uniquely private circumstances, to defend the corner of a group of servicemen and women who were deserving of the loyalty of service chiefs. Their loyalty had been unstinting, amidst circumstances that in many cases had been pretty awful, and Admiral West very clearly understood that. By the fall of the cards or aided by that sprinkling of fairy dust, I had stepped aside of all of the officers who had stood between me and the head of the Royal Navy, and my relief was dewy-eyed.

In the months that followed, Admiral West agreed changes that made a profound difference. With his support we were given the Military Chaplaincy at Amport for a weekend retreat to meet with senior officers. A signal was sent to every unit in the Armed Forces asking them to release anybody who wished to attend and to provide travelling expenses. It was a remarkable weekend, which brought together sixty LGBTQ personnel, every one of them moved and bewildered to be in the presence of so many of their kind. Lady ‘Rosie’ West remained a strong supporter and was on rare occasions a way to get a message to the First Sea Lord without my skipping through too many links in the chain of command. Admiral West set a new unabashed tone for supporting LGBTQ initiatives, which was followed by his successor, a face from my past, Admiral Sir Jonathan Band. On his watch I requested permission for our servicemen and women to march in uniform at Pride in London that summer. Chief of the General Staff of the Army and the Chief of the Air Staff flatly refused, and with some reluctance agreed that polo shirts with military crests might be used. I very strongly made the point that service personnel do not march in polo shirts in public; our uniform is our second skin. Thankfully, Admiral Band agreed. It was one of those occasions when the balance of risk and reward was not good. The reward was to do the right thing; the risk was to have the Naval Service embarrassed in the world press, just a few weeks following embarrassing press

coverage of the kidnap of Royal Navy personnel in the Gulf. In the footsteps of Admiral West, I felt that Admiral Band had been brave, and it needed to go well. Working with the MoD Press Office, I called every gay hack in Fleet Street. The story that followed was reported in every world news title from the Sydney Morning Herald to the San Francisco Bay Chronicle. There was not one dissenting article, and all were accompanied by remarkable images of those marching. In the weeks that followed, I was told that the Secretary of State asked why the British Army and Royal Air Force had sent their personnel to a public event at which they marched in civilian clothing. It is in many ways a pity that Admiral Band and I never crossed paths with time for the ‘fireside chat’ that might have lain to rest the ghosts of HMS Illustrious. However, when in full knowledge of the facts, he had taken the right fork in the road.

Even as late as 2006 and 2007, there were pockets of resistance, and General Dannatt, Chief of the General Staff, briefly became a focus (now General the Lord Dannatt). On a couple of occasions I leaked his position on LGBTQ issues to The Sunday Times, specifically about the General being reported as ‘apoplectic about being pushed by ministers to allow the Army to march in uniform at Pride’. Leaking to the press is a poor behaviour, but I had no other mechanism with which to address an issue with such a senior officer. By the end of 2007, I had gathered from the General’s office that he had experienced an epiphany and was now very positive about his LGBTQ personnel, so I desisted in my campaign. Before departing the service in May 2008, I requested a leaving call with General Dannatt. It was an unusual ask from a relatively junior Royal Navy officer, but he accepted my request. In our meeting he very earnestly told me that he had changed his view. Knowing that he had a strong faith, which might have caused him conflict, I thanked him for the support he had shown of late and left him with a challenge: to give the opening address in the Armed Forces LGBTQ Conference to be hosted by the Army in the following October, noting that I would not be there to leak to the press whether he had done it or not. The speech he made was reported to me as being very moving for those who attended, underpinned by this distinguished officer’s understanding of the fundamental importance of the covenant. I am always impressed by allies who support our community, because an understanding of the business case is in their DNA. I am slightly more impressed by those for whom this is a struggle from the outset, but one that they overcome.

The chance to do my duty was won by veterans who fought for change such that my career might not be dashed. When the ban was lifted, I did not turn my back on their support but instead turned my head towards the job of making the new policy work. I hope that my fellow veterans now understand that necessity.

Sometimes I wonder if there are senior officers or colleagues who feel I owe them an apology. There were certainly LGBTQ colleagues who winced at my unmilitary approach to this campaign, which at times verged on insubordination. Many of those struggling to find their way after the ban was lifted were keen to pass quietly in their daily military lives, but so many more needed the Armed Forces to pick up the baton. There is undoubtedly a generation of senior officers who rolled their eyes at the thought of the antics of the ‘unsinkable’ Craig Jones.

Today, I am thankful for the chance I was given to do my duty in the only way I know how. Nobody need ever ask me what I did during the war! These days, though, I check if a door is open before I break it down.

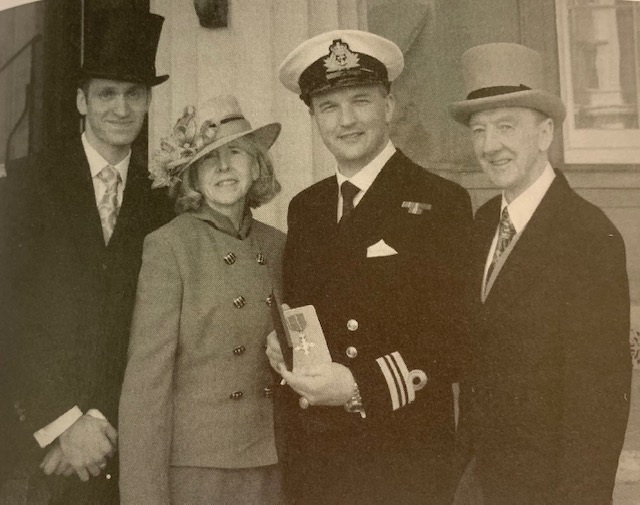

Buckingham Palace, 2007, with my parents, and Adam in a tall top hat!

…………………………………

We hope you enjoyed this exclusive look at Fighting with Pride. You can order a copy here.