Fighting with Pride: Lieutenant Commander Craig Jones MBE Part 1

We hope you enjoyed the first part of our Fighting with Pride blog series. Today we have the first part of Craig Jones chapter, The Unsinkable. The concluding parts of the chapter will be added over the next two days.

Fighting with Pride is out now.

The Unsinkable… Lieutenant Commander Craig Jones MBE

Royal Navy

My family link to the Armed Forces was tenuous; however, the service of an uncle as a radio operator shortly after the Second World War was enough to make us a naval family. My uncle had trained at what is now the Communications Warfare School at HMS Collingwood in 1953, an organisation that I was to command later in my career. And so, as a boy, I joined the 3rd Bingley Sea Scout Troop and five years later, found myself heading to Portsmouth University to undertake a degree in Economics, where I joined the University Royal Naval Reserve Unit.

In my first year at university I spent almost every weekend on the ship and my evenings at drill nights learning everything I could about the Royal Navy. After nine months, I applied for a reserved place as an officer and was invited to attend the Admiralty Interview Board. The AIB was a rigorous three-day assessment of a candidate’s potential to be an officer; it was my one chance to realise my dream and I worked night and day to prepare. In the 1980s, competition to join the Royal Navy as an officer was tough and the odds were against me. By the time I arrived at the AIB in early May 1987, I knew every aircraft, ship and missile in the Fleet, their engines, their radars and their sonars. Over many weeks, I’d prepared for tests in general knowledge, numeracy, English and military, and I sailed through the first day, which focused upon these written hurdles. Day two involved leadership tasks, and the other candidates and I forded water tanks and imaginary streams and caverns with wood poles, rope, pulleys and barrels, taking it in turns to lead each evolution. My leadership task involved using ropes and planks to bridge a cavern to a platform. I was lucky and my task came late in the day, when our skills were quite polished. I sighed with relief when the last man reached the platform.

Our final day started with a one-to-one interview with a female lieutenant called the ‘Personnel Selection Officer’ (PSO). The Lieutenant invited me into the interview room. Unlike other rooms at the AIB, there were no pictures of ships or aircraft, and the furniture was distinctly unmilitary; two comfortable armchairs were positioned by a window, separated by a coffee table and a colourful rug. None of this eased me away from my guard. I knew what was coming. She beckoned me to one of the chairs and I sat down. She started with some questions about my family and school life. She asked if we were a close-knit family and enquired about my brother. She then moved on to ask about university life and about my course, enquiring about my social time, skilfully weaving into the conversation questions about drugs, alcohol and gambling. She seemed pleased with my answers. She then asked me about friends and enquired whether I had any gay friends. I have never been a good liar and it was a great relief to be able to say ‘No’, and I added that I’d never met anybody who was gay. This seemed a very agreeable answer and she moved her interview on to talk about my university course and my anticipated grade of degree. After forty-five minutes she seemed to have the answers she needed and brought the interview to an end. I was relieved to leave the room – was it possible that you could tell that somebody was gay just by looking at them? I had no idea. My board interview started with naval knowledge and the Commodore asked me to choose one of the ships depicted by photographs on the wall and tell him about it. I turned round and saw a picture of my own unit’s patrol boat, HMS Fencer … Twenty minutes later, the Commodore interrupted to say that he’d heard quite enough about that patrol boat for one day, and so I won my place.

During the months of preparation for my final exams I often took time out to walk down to the dockyard and marvel at the warships that were moored sometimes two or three deep, many more alongside and still more in the creek beyond. It was then one of the largest military dockyards in the Western world and home to the majority of the Royal Navy’s sixty-five or so frigates, destroyers and aircraft carriers. It was May 1989 and I was due to cross the threshold at Britannia Royal Navy College Dartmouth in just three months time to commence my officer training, at a time when my young life’s ambition was almost within reach. It was a prize I wanted for myself, but I also carried the hopes and aspirations of my family. With little doubt, my mother saw me in the future as the commander of a frigate, married to an admiral’s daughter and living in a cottage in Hampshire with our two children, Charlotte and Henry, and a black Labrador. Life was to turn out differently.

On one of my journeys from the dockyard back to my student lodgings at Lorne Road, Southsea, that summer I passed a newsagent’s and was drawn to the magazine shelf. I purchased a copy of the Radio Times and returned to my rooms. I was staying in a large Victorian house with a kindly couple, Jacob and June. They had a strong Christian faith and quite specific house rules. By then I had joined the Royal Navy Reserve and they seemed in some way reassured that this might define my values in some positive way. My room was on the top floor. I closed the door behind me and checked the handle to make sure it was shut, turning the old rim lock until the deadbolt clicked. I then sat on the bed and stared at the glossy magazine cover – and there he was staring back at me, resplendently dressed as Marius from Les Misérables: Michael Ball. I appreciate that in recent times the mention of Michael Ball might bring forth an image of Edna Turnblad from Hairspray, or even a villainous Sweeney Todd, but I can assure you that in the 1980s, he was in every respect the perfect Marius – and hot stuff. Quietly, while staring at the bottom of the door to my room for fear of being disturbed, I muttered under my breath, ‘I’m gay’. Despite the fact that I was in an attic room at the end of a long corridor, I watched the bottom of the door for any shadow that might suggest I risked being overheard, and listened attentively before repeating the phrase ‘I’m gay, I’m gay, I’m gay’, a little louder each time. This was not the first time I had come to this conclusion. On reflection, my orientation had never been a grey area and I had had a range of gay crushes at school and university.

However, today I was prepared to say to myself – audibly, undeniably, with certainty and forever – that I was gay. On that day I accepted that I was destined to be different, a matter about which I had no choice. From the time of my earliest realisation, I saw nothing wrong with me, but accepted that others would.

………………..

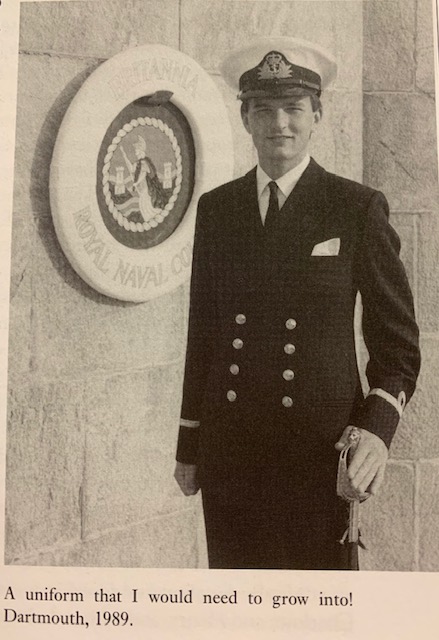

On 13 September 1989, a little before 4.00 pm, I drove through the gates of Britannia Royal Naval College in Dartmouth to begin the remarkable journey as a junior officer. We mustered on the parade ground in front of the magnificent towers and turrets created in 1905 by Sir Aston Webb. A feisty petty officer barked orders that few of us understood. My name was called in a list of cadets destined for ‘Blake Division’ and I gladly scuttled away to my accommodation. My group was escorted by a midshipman called Matthew Reed. He had joined the college from school at the age of 19 and would spend two years there. As a graduate my training was shorter, at just twelve months. Midshipman Reed had a shock of blond hair and an air of self-assurance and experience I had not encountered in somebody so young. If I had concerns about the conflict of my orientation with my career, the intensity of my first fourteen weeks of basic training certainly helped settle things down! From 0500 to midnight each day was crammed with activity: polishing, learning, running, jumping, more polishing and, occasionally, ‘The band of brothers’ pictured on our divisional yacht, with Matthew Reed and I on the far right. sleeping (but never for long enough). The only respite from the strenuous regime that prepares junior officers for service in the Fleet was representative sport. While at school I had raced sailing dinghies to notable success. Midshipman Reed was the captain of the college sailing team and he quickly found a place for me in the squad, and generally became my mentor. Thankfully, that involved weekends away from the college competing with the Royal Air Force and British Army, and I relished being freed from the exhausting activities at Britannia.

Matthew had bold confidence and was very well liked, and I was flattered to be included in his friendship group. He was fearless chasing a date and, much to everybody’s amusement, he struck up a relationship with the daughter of the Dean of the college. In the first week of term he had a lucky escape one night climbing down the ivy from her bedroom in the grand house her family occupied on the edge of the parade ground. It was typical of Matthew: devil-may-care, assertive and always smiling. On reflection, I suspect his love interest with the Dean’s daughter was not welcomed, and perhaps there was a sigh of relief as he left the girl behind when he completed training and joined the Fleet. Matthew was the first person in my life who epitomised the band of brothers that servicemen and women become when facing the challenges, adversity and hardships of service life. He ‘looked out’ for me during the greatest rigours of my training, and I benefitted from his brotherly kindness. Years later, when the wolves were at my door and chance brought our professional lives together, I took the greatest care to keep him clear of collateral damage.

The challenges of training were overcome and I was added to the list of cadets passing out at Lord High Admiral’s Divisions on 5 April 1990, where the Princess Royal would take the royal salute. My parents planned to visit for the event with my brother and his girlfriend – but I was missing a belle for the summer ball that followed Lord High Admiral’s Divisions. A few cadets would attend without escorts but I felt unreasonably conspicuous and wrote to an old school friend, Sarah. I booked a double room at a hotel in Dartmouth town. Quite frankly, this was a step too far in my wish to draw a smokescreen over the gaps in my life, but I got caught up in the moment. Whilst there may be folks out there who could ‘carry off ’ finding a carrot in a bag of parsnips, I was not one of those, and finding myself in a room with Sarah after the ball would, at the very best, only end in disappointment for everybody! The two weeks leading up to Lord High Admiral’s Divisions were peppered with anxiety. None of this was aided by being amidst a group of testosterone-fuelled cadets who had not seen their girlfriends for many weeks and eagerly anticipated all that the night would bring. My apprehension was in stark contrast, and each time I mentioned Sarah as my offering to the chatter about girlfriends, I couldn’t help but feel that my expression of enthusiasm

for the night was unconvincing. After a week of polishing my boots and sword, and the patent peak of my cap, the morning arrived. As I marched onto the parade ground, from the corner of my eye I spied my parents and Sarah. Whilst I was prepared to sign up to the principle of Nelson’s ‘band of brothers’, I felt that he might need to take a rain check on the sentiment ‘England expects that every man will do his duty’, which was carved into the stone of the facade of the college.

The Princess Royal, in her role as Lord High Admiral, was driven onto the parade ground in a black Rolls-Royce. She stepped out to be greeted by the Commodore of BRNC, who escorted her to inspect us. She stopped and spoke to me, asking where I was to go next. Slightly unglamorously, I was joining a Fishery Protection Squadron vessel and she quipped that there was honour in protecting fish. As my career progressed, I would occasionally meet members of the Royal Family and I was always struck by the genuine interest they showed in our servicemen and women. Over the period of an hour, she presented swords and we offered a royal salute, lifting our swords skywards, crossing them on our chests and lowering the blade to the ground in deference. We then hooked up our scabbards and marched off the parade ground. After celebration drinks and a long lunch we all retired to prepare for the evening. I had agreed to collect Sarah from the hotel at 6.30pm and began getting ready two hours before. I appreciate that, for many gay men, allowing two hours to get ready might seem not unreasonable. However, in this case, the passage of time had more to do with the challenge of the uniform.

For a ball, an officer in the 1980s would wear No. 7 Mess Undress with white tie. In my twenty-year career I faced many great challenges, but few matched the complexity of donning this uniform. The shirt had a stiff front with gold screw-in studs, cufflinks and a detached stiff wing collar. In the list of military offences, buggering the Captain’s dog was a lesser offence than wearing a pre-tied bow tie and, aside from being gay, I am also left-handed, which seemed to add to the challenge. There was then a white waistcoat with brass buttons, which needed cleaning and individually attaching (if you missed a dab of polish, it appeared as a green blob on the starched Marcella). The trousers were high-back cavalry style in heavy barathea, notably figure-hugging, and the ensemble was completed with a bolero jacket. Any man who believed that gay men and women were not serving in the military needed to chat to the guy that designed the uniform. It remains an outfit fitting of the most impressive of state occasions, and this was the first time I had been allowed to wear it. The finishing touch was my Gieves & Hawkes mess boots, which remain in my wardrobe today, purchased at the outrageous cost of £200. In 1989, this fabulous ensemble – crafted by the best military tailors in the world – munched £1,200 of my uniform grant, but I begrudged not a penny, and it has stood the test of time. Even the most plain of young officers stood the chance of a conquest in this uniform … if they could get into the damn thing (or perhaps, more importantly, out of it!).

Even in these early days, imagining what it would be like to attend a ball or function with a boy on my arm seemed too scary to dwell on. I pushed it to the back of my mind and returned to the crocodile nearest my canoe – Sarah! But with unspoken consent, we happily parted company a little after midnight, with nothing said or expected.

………………..

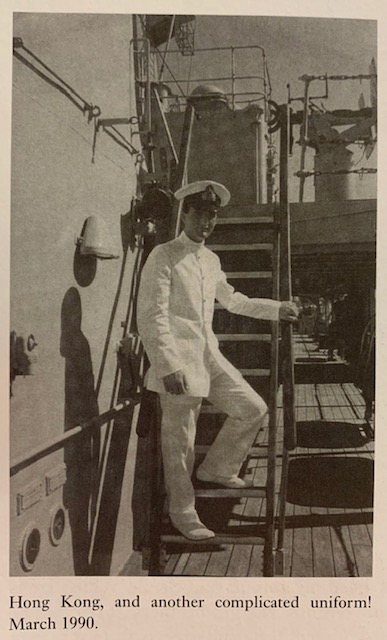

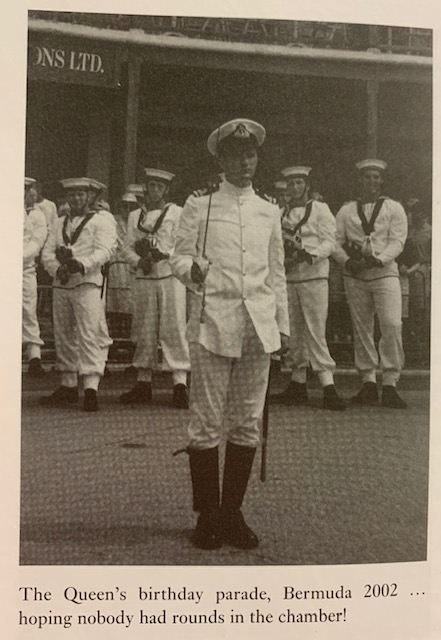

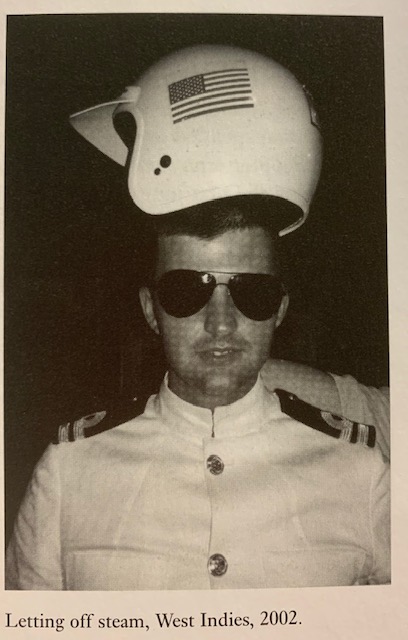

After a few months with the Fishery Protection Squadron and my training now completed, I joined Type 22 Frigate HMS Cornwall, on station in Bermuda as our West Indies Guard Ship. It was a plum appointment and much envied by others on my course who had been assigned to ships involved in fishery protection, hydrographic survey or deploying to the Falkland Islands (where the greatest excitement was seeing the penguins). Cornwall was one of the largest ships in the Royal Navy, with 280 men and women and commanded by one of the most senior captains in the Fleet. For the majority of my service in this fine ship, she was commanded by Captain (later, Vice Admiral) ‘Tom’ Blackburn. Captain ‘Tom’ was a gentleman. A lifelong confidant of the Duke of Edinburgh who was later in his career to become the Master of the Royal Household. I learned a great deal from him about subtlety in leadership and how much could be achieved by a calm, considered and measured approach.

To my surprise (on reflection), I took with me a large stuffed leopard named Tigger, gifted to me by my mother on my twenty-first birthday to replace an earlier version that was threadbare. Clearly the sentimentality of the stuffed toy overcame the potential simile to Brideshead’s Aloysius. Tigger became a popular personality in HMS Cornwall and was kept on my bunk opposite the officers’ pantry. The existence of Tigger seemed to be viewed as eccentric rather than ‘a bit gay’ and each morning on the bridge, Captain Tom would ask me how I was and how Tigger was finding the day. One morning, on returning to my cabin, Tigger had been swiped. I had the forenoon watch (0800–1200) on the bridge, so there was no time to search, and I fixed our position on the chart and took ‘charge’ of the ship from the officer handing over. The forenoon’s activity involved calibrating our Lynx helicopter’s gyro compass using the much larger gyros operated in the ship. Unusually, Captain Tom was in his chair on the bridge for what was quite a dull evolution. The helicopter thundered up alongside the bridge wing at the very close range needed to complete the calibration and I looked across from my position at the compass platform to signal to the pilot that we were ready to commence … and the furry paw of Tigger waved back from the pilot’s seat. Captain Tom was sniggering with delight. A little over a week later, I was on the bridge driving us towards a fuel replenishment with a large fleet auxiliary tanker. It was a dangerous evolution for a frigate of over 5,000 tonnes and a tanker that was considerably larger. The ships were required to position themselves alongside each other while this was under way, and there was no room for mistakes. I was firmly focused on our distance from the tanker and Captain Tom reminded me to keep an eye out for other shipping. Breaking my concentration, I tersely snapped back, ‘Yes Sir’, quickly scanned the horizon and returned my fixed gaze to the tanker. The replenishment completed, I handed the ship over to the afternoon watch and went down the ladders, past the Captain’s cabin on my way to lunch. As I passed his door, Captain Tom beckoned me in and asked if he had irritated me on the bridge. The comment vexed me; he was one of the most senior, respected and admired officers in the Fleet and whether he might have irritated me seemed to have no relevance. I was a very junior lieutenant by then. The only answer I could offer was to assure him that this was not the case. I skipped lunch, went to my cabin and sat thinking for a while about the meaning of his comment, until ‘the light turned on’. With great subtlety, Captain Tom had instructed me about how officers should treat each other. It was a clever admonishment by an officer who had far greater skills than fire and brimstone. Many years later, while a guest at Buckingham Palace, I was particularly pleased to cross paths with the then Vice Admiral Tom Blackburn, master of the Royal Household, after introducing him to my husband. His first words were, ‘And how is our Tigger these days?’

After returning from the West Indies and a few weeks’ rest, it was announced that we were to go to the northern Arabian Gulf. The Shatt al-Arab, a waterway that connected Baghdad to the open waters of the Gulf, had been clogged with ships and silted, and in the immediate aftermath of the first Gulf War, it needed clearing. There were concerns that as these vessels were floated and dragged into open waters, contraband, people or munitions could be smuggled, and boarding by boat was considered laborious and relied upon the goodwill of other regional protection forces. The Commander-in-Chief Fleet decided that a new approach was needed and HMS Cornwall was directed to ‘stand up’ a boarding team that would undertake these boardings by helicopter fast rope. Until then, helicopter fast rope (jumping out of helicopters on ropes) had been limited to Royal Marines, who undertook a more substantial course of training in combat warfare. I had some ground to catch up. After a week at the gunnery school at HMS Cambridge, taking apart and reassembling my 9mm browning pistol, my petty officer and I went to RAF Netheravon and completed a Helicopter Fast Rope Instructor course, joining a group of fifteen Royal Marines. Over a period of weeks we jumped out of a wide range of helicopters to practise our drills and, aside from a few minor ankle bruises and despite our blue uniforms, we seemed as competent as our dark green colleagues.

After an exciting few weeks, I returned to the ship on the Sunday night full of enthusiasm for sailing through Plymouth Sound the following morning at the start of our deployment. I stepped into the bar to find my fellow officers muttering in hushed tones. I grabbed a beer from the fridge and listened intently. Able Seaman Evans had left the ship accompanied by the Special Investigation Branch on Friday: apparently, he was gay. I was immediately struck by the compassion of my fellow officers. Nobody was gleeful at this turn of events, yet no one suggested it was unjustified; it was just necessary. I finished my beer and went back to my cabin, where Tigger was perched on my bed. It was fair to say that I was having the time of my life and this felt like a stark warning shot across my bows. It was the bluntest reminder of how quickly everything could be lost.

The following morning, I picked myself up and climbed the ladders to the bridge to don my headset to take HMS Cornwall through Plymouth Sound on the first leg of her journey to the Gulf – a fuelling stop in Gibraltar. On our way south, my petty officer and I selected our boarding team, which would include two Royal Marines who had been embarked for the deployment. We began their training as we dashed through the south-west approaches, starting with ropes suspended in the aircraft hangar and progressing to jumps from our Lynx helicopter onto the flight deck, bows and eventually onto the bridge wings. These were the first jumps we had made wearing bulletproof vests and with the extra weight, keeping control in descent was much more challenging. In the last twenty-five years, technology has improved the materials used to stop the passage of a bullet and the vests are now lighter and more compact, but in 1993, they were heavy and bulky. We completed our preparations by firing a few magazines from our pistols and rifles against a balloon target towed from the back of the ship. It burst on the first hit and the galley sent up a couple of their industrial scale baked bean tins, which were dropped from the quarterdeck to provide a shiny target in the clear blue waters of the Mediterranean.

After a swift transit of the Suez Canal, we sighted the Straits of Hormuz and the ship was brought to its highest state of readiness: ‘Action Stations’. It was early in 1993 and there remained a great deal of tension in the region. Little more than a year before, HMS Gloucester, under the Command of Captain ‘Fighting Phil Wilcocks’, had shot down a Silkworm missile bound for the battleship USS Missouri in the waters we passed through, and we remained at action stations for a few hours until the confined waters of the straits were behind us.

The Northern Sector of the Gulf was controlled by the USS Nimitz. At over 100,000 tonnes, this mammoth aircraft carrier was twenty times the size of a frigate. She commanded the water and airspace around her with notable firmness, and anything larger than a seagull risked being shot down for being off station. Soon after our arrival in theatre, Nimitz allocated us two vessels that were being towed clear of the Gulf to board. We were the first fast rope team to operate in the area, with US and allied nations launching boarding parties in a wide range of shabby motorboats. As our team prepared to board the Lynx, I felt some sense of occasion and had one of those ‘the eyes of the nation’ moments. Our Principle Warfare Officer, Lieutenant Commander Roly Woods, who had become a friend, shook my hand as I got into the helicopter, with the parting advice: ‘Don’t fall off the rope or shoot yourself in the foot.’

Our target vessels were a tug and tow. The towed vessel was the Thalasini Mana, which had been silted in the Shatt al-Arab for many months. Her tug was named Dubai Moon. We agreed to tackle the towed vessel first; she would be more complex to search and there was a greater chance of something untoward. After circling our target in the Lynx to observe the crew and the decks we made a steep decent to hover over the bridge wing. The bridge roof would have provided a flat and open site for us to descend to; however, I was concerned about the radars mounted directly above and had no wish to get my team too close to their energy blasts. We dropped the ropes and left the aircraft for an uneventful 50-foot decent to the merchants’ deck. The master had embarked a pilot who spoke perfect English. I deployed my team to the decks to take a look around, keeping my Royal Marine bodyguard close. Our sailors had the somewhat clumsy SA80 assault rifle, which was far from ideal when clambering around ships. The Royal Marines were carrying the Heckler & Koch MP5, a much sleeker weapon; reliable and with a shorter frame, it would have been my weapon of choice but as the only officer in the group, I got a Browning 9mm pistol. The Browning was designed in 1935 and was one of the simplest handguns in the world. My pistol came with a green canvas holster, which shrunk in contact with salt water to such an extent that it was virtually impossible to draw the weapon. I could not help but think that it might have been designed by the Army to be the weapon of choice for Royal Navy officers.

The master of the Thalasini Mana had clearly not anticipated having people ‘drop in’ on him and he looked a little startled. The pilot had experienced a ‘boarding’ before and after an exchange in Arabic, the master hurriedly pulled together his ship’s log, papers and inventory. I carefully checked through the documents, which seemed in good order, and invited the master to escort me as we searched the ship. As we passed from room to room, I carefully observed him. He was nervous, but not nervous enough to be guilty. We opened Thalasini Mana’s cavernous hold, but it was empty and I reported back to the ship on my Cougar radio in code that I was satisfied that the vessel was compliant with the embargo. We disembarked and undertook a cursory check of the tug before returning to the Cornwall’s flight deck. Shortly after supper that night, I was called to the Captain’s cabin. Captain Blackburn had a serious look, which surprised me, and he and our Executive Officer told me that the father of one of my men had been killed in an oil rig explosion in Mexico. It was a sombre moment and such news at sea brought back to us the vulnerability we all faced in a life spent thousands of miles from our loved ones. I was asked to sit with the sailor that night until we could steam a day early into Dubai to get him home. The sailor was a Glaswegian with whom I got on well, so I grabbed a case of his favourite Courage Sparkling Beer and settled in for a long night. It’s pretty awful to lose a parent at a young age, but all the more difficult to hear the news so far from home and family. The role of a divisional officer at the front line places you in the privileged position of being able to make a difference, and I never took that duty lightly. He cried a great deal and we drank until he drifted in and out of sleep. Then I packed him a bag and as soon as the gangway went down in Dubai, he was whisked away in a taxi by the Naval Attaché.

………………..

After some weeks in the Gulf conducting our operations, we headed east for Singapore, where I was due to leave the ship, my tour of duty being completed. In my range of duties in HMS Cornwall, I was specifically responsible for the welfare of the ship’s largest mess deck, which provided accommodation for fifty-seven men, defined by its location marking ‘3 Hotel Zulu’ but known affectionately as ‘The Zoo’. I was fortunate to be a popular officer with my teams and I spent a fair bit of time with them in the mess deck. There was a fine line between knowing when to arrive and when to leave. They were a lively bunch and many had served for more years than I had lived, but I had their best interests at heart and they took some pride in looking after their youthful 22-year-old officer. On special nights, such as returning up the Channel to our home port, I was never short of an invite – it was getting away that was more problematic! As we passed through the Malacca Straits, getting ever nearer to Singapore, I got the inevitable invitation to a leaving ‘run ashore’ at the famed Fire nightclub. By then I was a veteran of the ‘run ashore’ with the boys and had mastered the art of being in the right place at the right time and always finding the right moment to slip away. Once on a visit to Campbelltown, the leading seaman in charge of The Zoo had thrown me through the saloon doors of a pub to avoid me witnessing a fight between one of my sailors and a marine engineer from the ship. The next day at Captain’s disciplinary table, I was able to represent him because I was not a witness to the altercation. It was good common sense and naval law at its finest.

We docked in Singapore and at 6.00 pm I appeared at the top of the hatch to The Zoo as directed. A tin of Courage Sparkling Beer was thrust in one hand and I was grabbed by my other hand and pulled through the hatch head first. All fifty-seven of my men were lined up for a photograph and the leading hand of the mess gave thanks for my time. It’s not unusual to get a tankard or something akin at these occasions, and that was my expectation, but The Zoo had been imaginative. ‘And tonight, Sir, you will be jetting off to Sembawang with Able Seaman Jarvis, where we have arranged two lovely ladies for you.’ Rarely have I felt quite so horrified. Seemingly, it was a mess tradition to send the youngest member of the mess deck and their mess deck officer to a brothel – and these experienced tars knew just the place! More worryingly, Jarvis looked delighted with the idea. Although barely 18, he was a little over 6ft 3ins and had experience well beyond my boundaries. He really did seem to be very streetwise for such a young chap. He sidled up to me, rubbed his hands together and whispered collusively, ‘We’re gonna have a right old time, Sir, eh?’ I took a long gasping swig of my CSB. It was certainly going to be a long night. ‘Oh yes, can’t wait!’ I replied.

After a few more tins of CSB, the forty or so mess members who were not on duty stepped over the gangway in the direction of the nightclub. Fire was an eye-opener for an officer who had led a fairly sheltered life, but my sailors seemed to fit in very well indeed. Jarvis was enjoying the moment and holding court with a group of younger mess members who were exchanging ideas on techniques. I was with my leading hands, doing my level best to appear cool. Drinking seemed to help, so I kept going until Jarvis appeared in my shadow at a little after midnight. He had in his grasp a little over £90, which the mess had gathered up to send us on our way, and a few minutes later I found myself in a taxi en route to a brothel in Sembawang with Jarvis, who was in a state of noticeable enthusiasm. After the customary altercation with the taxi driver about the tip, we stumbled through the door of the ‘Orchid Rooms’ to be greeted by a ‘manager’ who looked like an extra from Raging

Bull, as well as a lady who was a little over her teens and an older lady with rather thick make-up but a cheery face. Quick off his feet, Jarvis grabbed the hand of the younger lady and disappeared down a narrow corridor of rooms, and I heard a door shut behind them. At this point I theoretically had two options. I could have run, but I was in a tricky area of Sembawang, and Jarvis, with his stature and streetwise manner, was my safe ticket home. The older lady beckoned me with her painted finger to follow her, saying, ‘I’m Mae – what about you?’ I mumbled ‘I may not’ under my breath and followed her. There seemed little choice.

The room was dimly lit and had an air of Yardley about it. There was a bed with a candlewick bedspread and a shower in the corner, which would not have passed muster for Captain’s rounds, and an equally grubby looking fridge. … And then I took an enormous risk. I had never ‘come out’ to anybody, but there was a kindness in her eyes and I really couldn’t see an alternative, so I sat down by her side and, with a conspiratorial tone, I told her I was gay and needed to make sure that Jarvis was none the wiser. She seemed quite pleased and explained that all that discretion would be quite expensive. I gave her the £40 that Jarvis had left me with. Given that her duties would be limited, it seemed very fair to me, but she looked a little disappointed, so I slipped her another £40, which lightened the mood. ‘Go water hair look wet, go shower, shower, shower, shower,’ she said emphatically. With an eye on my wallet, I followed the instruction, then dried off and got dressed again. She opened the fridge and grabbed two Tiger beers and we sat on the bed and cracked them open. Every five minutes she got up and opened a wooden flap on the wall, through which she could see into the room next door, where Jarvis was no doubt quite busy. After three or four checks, she said, ‘Hey sailor, he’s leaving – you wait another five few minutes. Officer should last longer!’

With my time up I moved towards the door and the cheery lady asked for another £20. ‘What for?’ I asked. She pointed at the Tiger beer cans. She had a point and this seemed a poor time to haggle. I opened the door and saw Jarvis at the end of the corridor in a James Dean pose leaning against a door frame, bare-chested with his T-shirt nonchalantly over his shoulder and a cigarette drooping from his mouth. As I walked towards him, Mae shouted after me, ‘You Lieutenant got huge cock, very hard, you come again I give you big discount.’ There was honour in her trade. Jarvis looked a little less cocksure by the time I got to him.

We jumped in a cab and returned to the ship. For my remaining forty-eight hours in HMS Cornwall I was a legend, and I basked in the sun.

………………..

Fighting with Pride is available to order directly from Pen and Sword Books.