Children at Sea: Lives Shaped by the Waves by Vyvyen Brendon

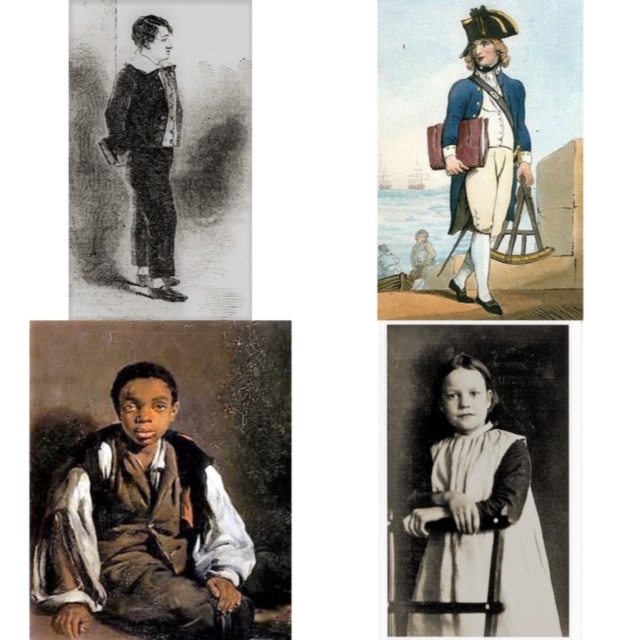

I decided to present my subject not as a general history but rather as a collection of life stories set in Georgian and Victorian times, illustrated here with pictures not used in the book. My eight characters all embarked on sea journeys as children and were never the same again. I had five criteria for selecting them.

1 All left home and parents when they were under sixteen. Five boys enlisted as sailors in the Royal Navy: George King as a marine private, Othnel Mawdesley, William and Charles Barlow, and Sydney Dickens as midshipmen. Joseph Emidy was kidnapped from Africa as a child slave and granted his freedom as a teenager, only to be captured by a naval press-gang. Of the two girls, Mary Branham was transported as a convict and Ada Southwell was sent as a Barnardo’s migrant to Canada.

2 Their lives were all shaped by this initial voyage. Such were the dangers of shipboard life that Othnel Mawdesley, William Barlow and Sydney Dickens met the same fate as my great grandfather – they died at sea before they were thirty. Only George King and Charles Barlow retired to a safe haven after a lifetime on the ocean. The slave, the transported convict and the migrant remained exiles all their lives, uprooted from home but sometimes able to find love and sustenance in new lands.

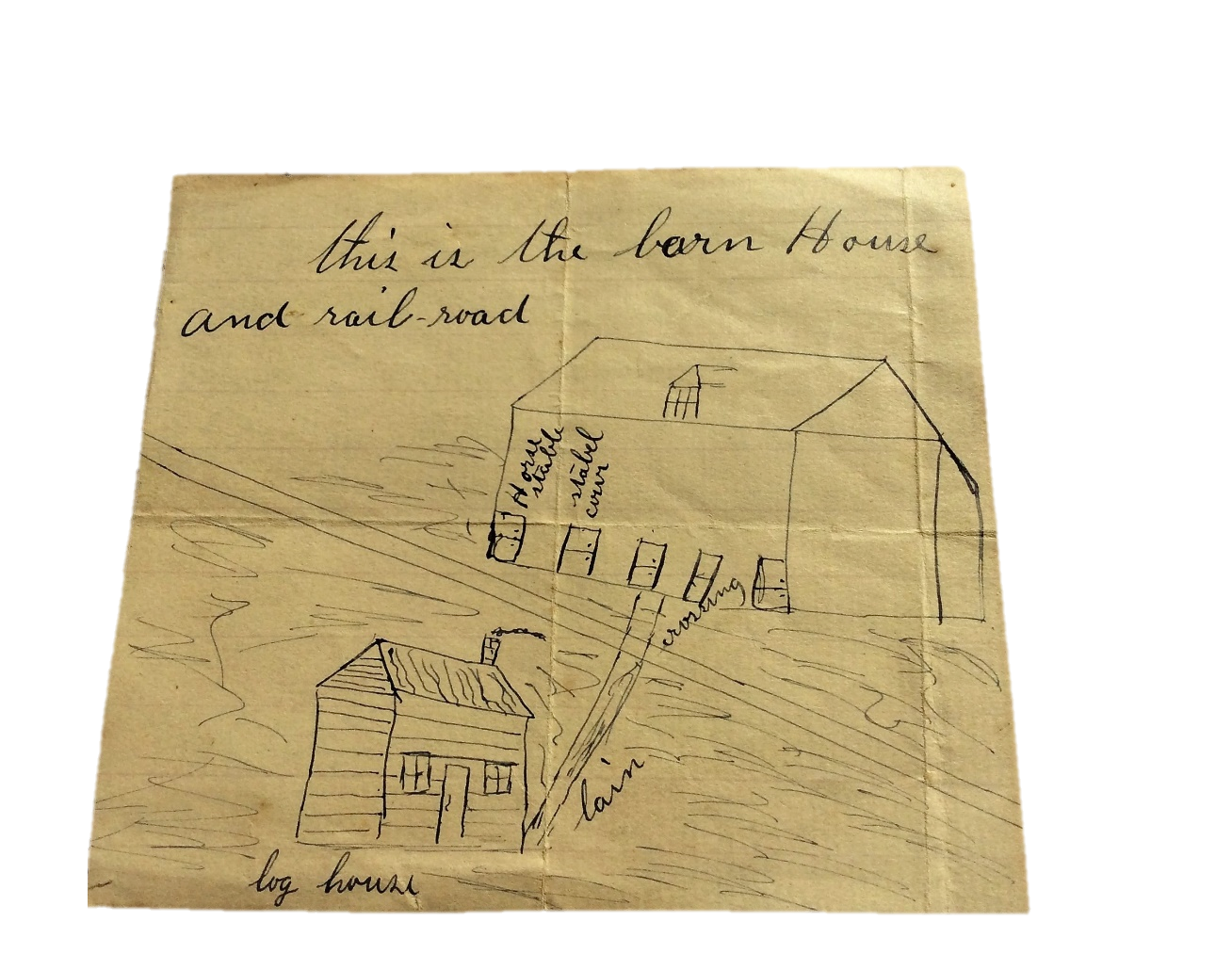

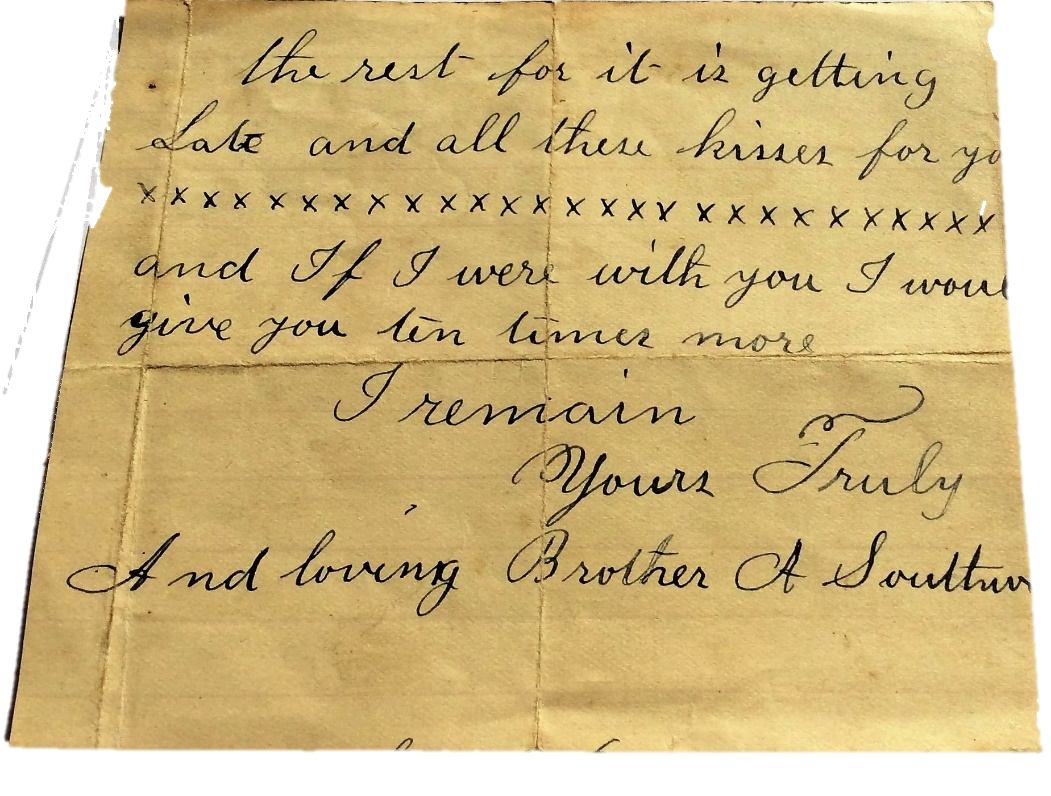

3 I chose characters for whom I found original sources. Windows into their lives were provided by largely unpublished letters and memoirs: the Barlow correspondence exchanged between members of this large scattered family; Midshipman Mawdesley’s journal of captivity in Spain during the Napoleonic Wars; the autobiography of George King recounting his childhood as a foundling, his fighting at Trafalgar and his many years at sea; the letters and novels of Sydney Dickens’s celebrated father; Joseph Emidy’s story as told to one of his Cornish music pupils; the memories of Ada Southwell’s husband and the correspondence of her dispersed siblings. Of Mary Branham, a poor and probably illiterate convict girl, there remain only the records kept by her captors.

4 I aimed to make a socially diverse selection and that depended on the available evidence. All four midshipmen hailed from comfortable families used to writing letters and journals and with the means to preserve them. But it was hard to find sources from poorer backgrounds because of low levels of literacy. Thanks to an exceptional teacher at the Foundling Hospital, however, George King was able to record his life as a common seaman. Later in the 19th century the school-taught Southwell children could write to each other and to their destitute mother, whose replies were penned in a public house by a friend. During a childhood spent in slavery Joseph Emidy somehow acquired the musical and writing skills which equipped him for professional life in Britain. Very few girls went to sea as sailors though some were captured as slaves or transported as convicts and more were shipped off as indentured servants. So I’m pleased that Mary Branham and Ada Southwell make up a quarter of my sample.

5 I wanted to reveal the different ways in which my characters reacted to separation from home and family. The historian can never conjure up inner lives in the manner of a novelist. Even so, in my book readers will glimpse ‘tales of transformation’ akin to those contained in Emma Donoghue’s ‘fact-inspired’ stories, Astray, which helped to inspire me. Some youngsters found the strength to face new challenges; others suffered from homesickness or heartache; still others lived a ‘vagrant gypsy life’, as John Masefield put it, or simply ‘went to the dogs’. As sailors or migrants left their native shores they could not know what lay ahead or how their lives would be shaped by the waves.

You can preorder a copy of Children at Sea here.