Celia looks at understanding our deeper roots in the context of cemeteries and graveyards

Author guest post from Celia Heritage.

I was 8 years old, and I already knew what I wanted to be one I grew up! Not a genealogist – but a jockey!

I had also toyed with the idea of becoming a librarian as I loved reading and books, but it was horses and racing that I was mad about for many years, until the world of university (history and music) took over in my late teens and early 20s. What I didn’t know, aged 8, was how instinctively in touch with my roots I was. Although no-one else in my immediate family rode or owned horses, unbeknown to me my love of horses and racing was in my roots!

An on-the cuff comment by my Mum several years later, to the effect that she wondered if we could be related to the well-known racing family, the Dickinsons, got us both thinking. Mum’s grandmother was a Dickinson and as a teenager she had visited her Uncle George Dickinson in Lancashire who bred and trained horses (although I knew none of this until then). It was this, and the many stories Mum started to tell me which had been passed down to her by the same Uncle George, which sparked my fascination with family history. I wanted to know the names of my ancestors, where they came from, what they did and what they were like. Intuitively I was reaching out to discover where I belonged and find out about myself, for yes, you guessed it we were indeed related.

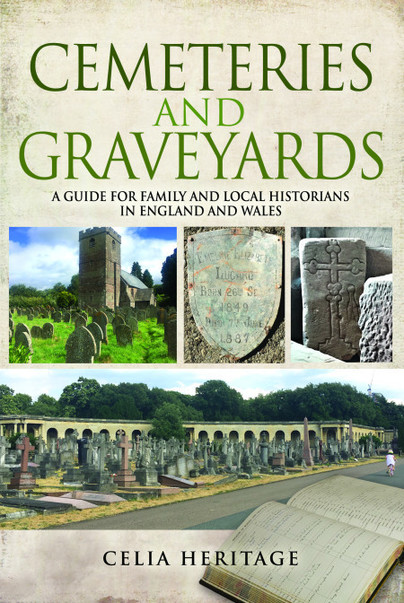

A fascination with our ancestors, who they were, what drove them and what they were like is strong in many people (hence the popularity of family history as a hobby). For many of us, the past is key in explaining how we got here; it gives us a sense of belonging and a link to those who have gone before. There is something very special about standing before the place where you know one of your forebears was laid to rest and even if you don’t know the exact spot, simply just being there in that churchyard or cemetery where he or she lies. It is also a form of paying our respects, and this way of thinking has formed part of the culture of many societies over the centuries. Locating burials and related sources such as memorial inscriptions can be tricky for many reasons and in the final two chapters of Cemeteries and Graveyards I look at this aspect in detail as well as dealing with the unexpected – where burials have been exhumed and relocated. Of course, if you are lucky enough to find that your ancestor’s memorial still stands, you are likely to also discover vital genealogical information for your tree. But its not all just about family history; those people buried in our local graveyards and cemeteries were also a part of the history of the places where they lived and died. Often, as researchers, we get as addicted to tracing the history of people to whom we have no blood relationship. Each person has their own unique life story no matter who they were, and finding their resting place is, arguably, the end of that story.

Whatever drives our individual needs to visit our ancestral resting places, looking to the past for an understanding of the present, and potentially of the future too, has always been important. Veneration of ancestors, or ancestor worship, played an important part in certain societies such as the Malagasy tribes described in Chapter 1 of Cemeteries and Graveyards and, in this chapter, I also look at how our perception of death, what happens after death, and how the ways in which we commemorate death have evolved from pre-history to modern day. Conversely there are many common themes which cross over between cultures and that are constant throughout time.

One of my other early childhood memories is of an old dictionary that sat on the shelf in our bookcase at home. It was a Nuttall’s Dictionary and again, aged about 8, I was fascinated by this book. It was the appendix entitled “Etymology of Place Names” which really drew me to this book. I learned that “The etymology of the name of a place has generally some bearing on its history and physiography. When different races occupy a county in succession, they leave behind them the names they have given to the localities in which they have lived: and these place names not only record the people who gave them but the physical features of the country when they were given.” Here were the embers of what was to become a fascination with the landscape and its evolution and a growing awareness that we cannot fully understand the lives of our ancestors if we don’t set them into their historical context, both within the landscape, and within the communities in which they lived and which they therefore helped forge.

As I grew older my fascination with family history and churchyards and history on the ground evolved. I started to take an interest in the churches – not just imagining my ancestors being baptised, buried, or married there but the history of each church itself and its individual setting in the landscape. I noted how church, landscape and community are intertwined.

Our parish churchyards form an essential part of our archaeological heritage. Despite the fact that very few have been fully excavated, since their early origins and history are almost totally undocumented, it is still the archaeology that speaks loudest, much of this being rescue archaeology in the face of building and other works. This was one of the most exciting chapters for me to write since so much about the origins of our earliest parish churchyards is open to debate. No doubt the discussion will continue.

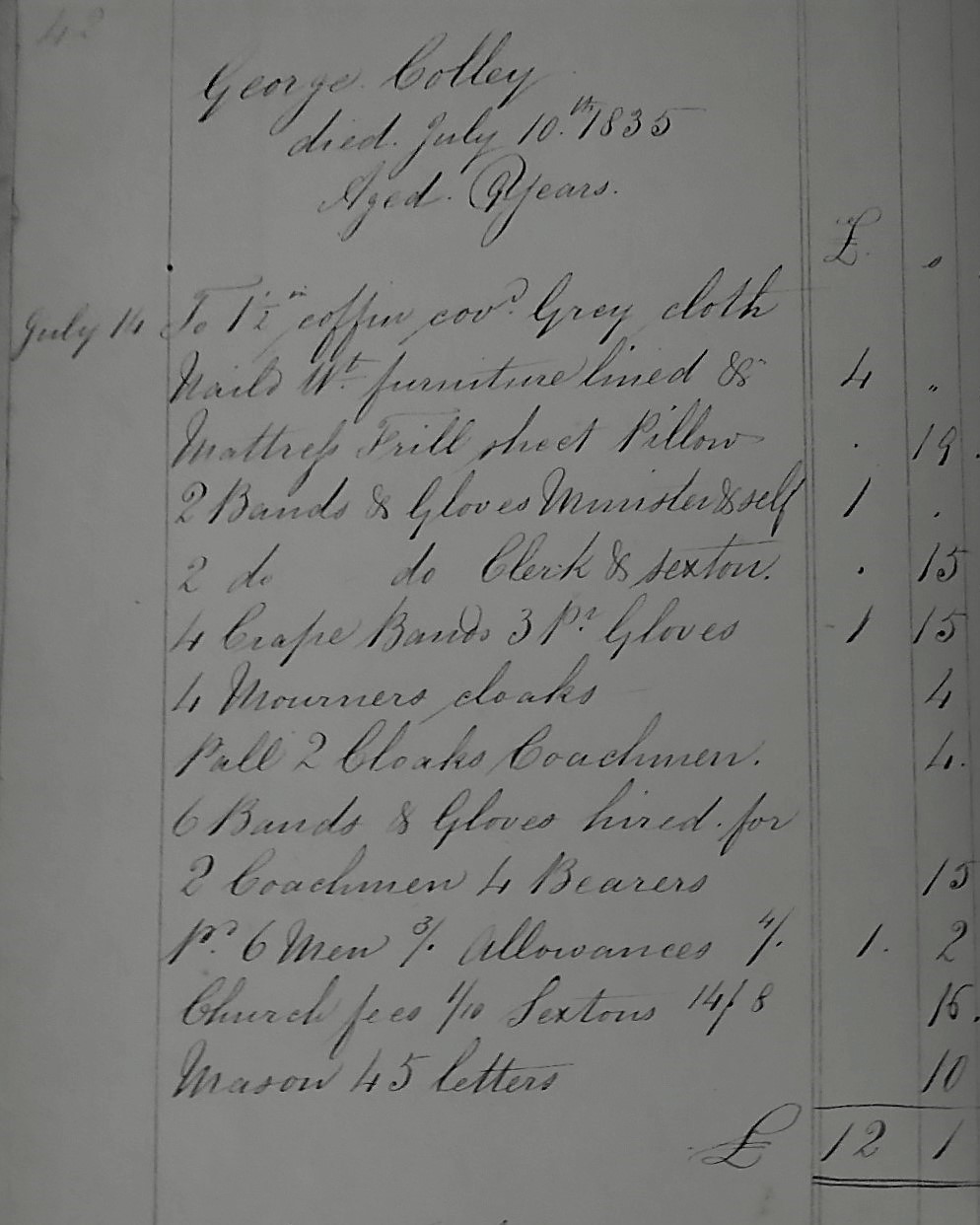

Among those with the family history bug, there can be a tendency to focus in on collecting names and adding new generations to family trees to the exclusion of much else. Even for those family historians who are keen to flesh out their ancestors’ lives with sources such as newspapers, parish chest records and wills, many don’t think to look at sources which are not typically billed as “genealogy sources”.

With so many maps, books, PHD dissertations, and archaeological reports now easily available online, or for sale via the internet, there is so much more waiting for the enthusiastic researcher! Embracing this wider approach to research is infinitely more rewarding, since it brings an understanding of essential local, social, and political history which would have directly impacted on our ancestors’ lives. With all these tools at our disposal we can really start to understand the lives of those who came before us. In my book, I provide tips and advice about many other sources that can be used, together with case studies which highlight potential problems you may come across in your research. I also illustrate how to use sources in combination, to research in a strategic and optimal manner that will bring you the best results. Most importantly too, I look at getting out on the ground and locating the sites of defunct graveyards – of which there are many – particularly those once attached to institutions or non-conformist churches. This is such fun! History is not just about sitting in front of a computer or studying old documents – they are often the springboard to an exciting day’s adventure outside in the fresh air which will often give you a new perception of your documentary research.

And this brings us back to that sense of belonging: there is even more emotion and excitement attached to our explorations if it is our ancestral landscape we are exploring. We have a deep-seated connection there to our ancestral past and this is just one thing which makes cemeteries and graveyards such an important part of our heritage.

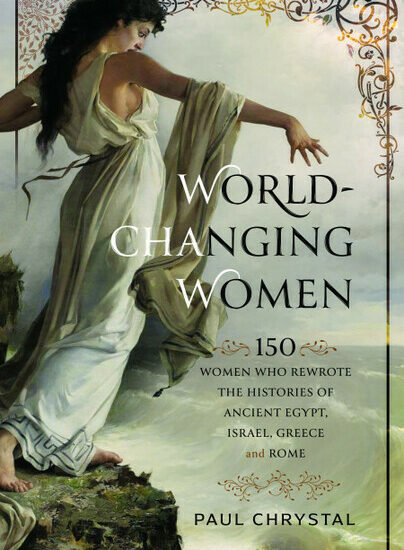

Cemeteries and Graveyards is available to order here.