Bringing ‘Dark Ages’ Women into the Light – Annie Whitehead

The subject of my first novel, Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, daughter of Alfred the Great, was someone whose life was somewhat of a paradox. She ruled as a queen but wasn’t given the title. She clearly led a remarkable life but wasn’t much remarked upon. Her story was crying out to be told, yet it was surprising to discover that – and to the best of my knowledge this still holds true – no one else had told that story in the form of a novel.

My subsequent novels featured equally interesting female characters, including Ælfthryth, the woman who is often cited as being the first crowned consort of an English king, and who went on to find herself accused of witchcraft and regicide.

She and Æthelflæd also featured in my first nonfiction book, Mercia: The Rise and Fall of a Kingdom. The book wasn’t exclusively about women, but some interesting ladies certainly emerged. One, a powerful abbess who became embroiled in a legal dispute with the Church, subsequently lost some of her religious foundations but hung on to an extremely lucrative abbey. Another, a queen, had coins minted with her image on them, yet most of what we hear about those two women is salacious at best.

I often say that in 1066 a line was drawn across history. We know, of course, that there were sweeping changes and not just in the replacement of the king. The old order was not so much removed, as obliterated. Gone was the English nobility, to be replaced by Norman overlords, given land in reward for services at Hastings.

What did this mean for the women of Anglo-Saxon England? For many, it meant new husbands. Laws changed, and women had fewer rights. What we sometimes forget though is that the people who wrote the history changed too. They were still monks, but now they were Anglo-Norman monks, writing to a different brief. And the tales they told of the women who lived before the Conquest often contained stories of witchcraft and murder, including the above-mentioned ladies, the abbess and queen of Mercia, both of whom were accused of murder by the later chroniclers.

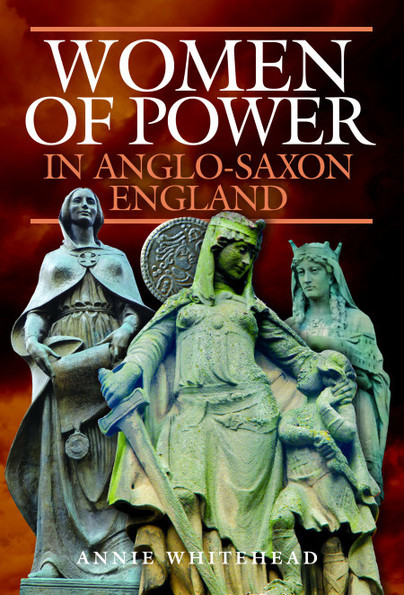

However, if we look hard enough, we can find plenty of information to restore the reputation of these women, and put their lives in context. This is what I’ve set out to do with Women of Power in Anglo-Saxon England (published by Pen & Sword Books, May 2020)

Earlier sources tended to be less florid in their descriptions of these women (although one near contemporary did accuse a queen of accidentally poisoning her husband) but if we look closely though, and listen, we can hear these women talking to us and we can take these sometime brief references, link them to the relevant archaeological finds, and use them to understand the women who provoked the comment.

In the very early years of the Christian church, women were hugely influential. Some historians have interpreted Bede’s words as suggesting that queens persuaded their husbands to renounce paganism and embrace Christianity, and while it might not have been so clear cut, as I’ve explored in the book, the royal women (and they were usually royal) certainly held sway on a good many religious matters. One, Hild, was credited with the education of no fewer than five bishops and played an important role at the synod of Whitby, where the decision was finally taken about when to celebrate Easter. Her kinswoman, also an abbess, was called upon to give her testimony when one king died and another was to be chosen, her words swaying the decision. Whitby was a great cultural centre, with an extensive library, and evidence shows that books were produced there by the nuns.

Most of the abbeys were double houses, where both monks and nuns lived, and were presided over by abbesses who wielded extraordinary power and were landladies of huge, wealthy estates. This power often brought them into conflict with the Church, and this might partly be why, particularly as the double houses declined in the later part of the period, the chroniclers (almost always monks) sought to tarnish their reputations.

Women often travelled hundreds of miles from one kingdom to another, bringing not only their religion and their household with them, but also their important bloodlines. One princess’ blood was rich enough to start a war. We know her name, Acha, and we know of the bitter and bloody feud which followed her – probably forced – marriage. Sadly though, while we can piece together most of the significant events of her life, we don’t know where and when she died.

Acha’s bloodline was extremely important, giving her offspring claims to both the northern kingdoms. Other queens had more direct influence on politics, many ruling as regents for their sons, and some even going to war on their behalf. These regents included Ælfgifu of Northampton, who ruled Norway on behalf of her son by King Cnut, and Queen Ælfthryth, mentioned at the beginning of this piece, who retained influence on her son, Æthelred the Unready, into his adulthood and even after he married.

Although we don’t always have the complete picture – such as the details of Acha’s death – we don’t have to simply rely on the monastic sources. There are many extant letters, charters, and in the case of Queen Cynethryth, above, coins, which all help enormously to build up a picture of the lives of these women. Some of the letters are, indeed, written by the women themselves and add to a growing body of evidence pointing to high levels of literacy among women at this time.

Women of Power in Anglo-Saxon England mentions over 130 women by name, presented chronologically and in family groups, and encompassing all the major kingdoms of England: Northumbria, Kent, Mercia and Wessex. The aim was to bring these women back out into the spotlight, and luckily, once I began digging, the documentary and archaeological evidence was there, waiting for me.

Women of Power in Anglo-Saxon England is available to preorder now from Pen and Sword Books.