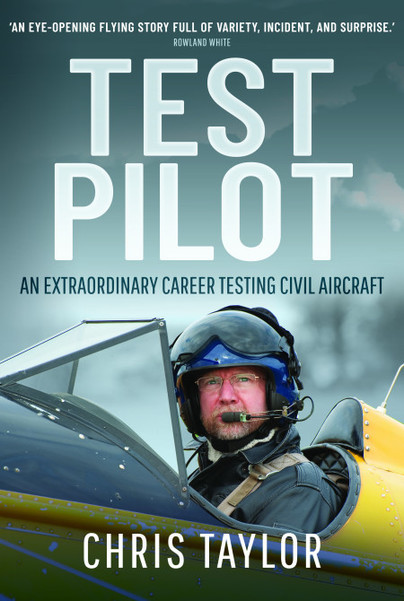

Author Q&A – Chris Taylor

Since writing my book ‘Test Pilot’ and its publication in March 2022 I have been asked numerous questions about my test flying – particularly the aircraft I have been fortunate enough to fly. I have listed just some of the questions I’ve been asked in recent days and the answers I’ve provided.

What is the oldest aeroplane I’ve flown?

This is perhaps the most straightforward question to answer. In 2005 I visited the Shuttleworth Collection at Old Warden as part of my regulatory oversight. I was invited by the Chief Pilot to fly the Avro 504K G-ADEV which had been built in 1918 as a training aircraft in World War One. I was still growing my experience of open cockpit aircraft at the time but thankfully I had flown a Tiger Moth and Stampe bi-plane previously. The aircraft was powered by a 110hp leRhone nine cylinder rotary engine. The aircraft itself flew much like a Tiger Moth with weak directional stability typical of all aircraft from that period. There were two very distinctly memorable features of the flight. Firstly controlling the engine power was extremely difficult. There was no conventional throttle that metered the fuel. Instead the engine was set up to pretty much run at max chat all the time. Although this could be modulated to some degree in cruise flight if the power was to be reduced markedly to commence a descent, and subsequently land, the engine had to be blipped with the electrics to the engine repeatedly disconnected with a ‘blip switch’. Needless to say, being a rookie I failed to get this quite right on my approach and flew one of the many engine-off landings of my career to date. Secondly the lubrication system of the engine was filled with something that resembled castor oil. The system was designed to ‘piss out’ the used oil constantly. By the time I landed my flying suit was soaked in the stuff and continued to smell for at least a dozen aggressive washing cycles.

What has been the most fun or enjoyable test flight I’ve flown?

As my book ‘Test Pilot’ explains I spend most of my time when airborne worrying about all the bad things that might happen and cause my aircraft to plummet earthwards so I have little time to ‘enjoy flying’. That said flying an AS350B3 Squirrel in Italy definitely provided some of my most memorable and exhilarating moments. I had been tasked with conducting a flight test programme on this particular aircraft to clear an external rear view mirror. The aircraft was used extensively for mountain rescue and based at Courmayeur in the foothills of Mont Blanc. I had to fly extensively around the mountains and valleys to achieve the testing required. It was particularly ‘gobsmacking’ to be flying at 12,000 feet and looking both a long way down to the valley below and still looking up to the mountain tops well above me covered in pristine white snow against a cracking azure blue sky.

What has been my biggest cock up in flight test?

Although my book ‘Test Pilot’ mentions this I have documented the story more fully in my next book. I’ve included the story here:

I was in my first year as an instructor at the Empire Test Pilots School and had been tasked to fly the Westland Scout. I elected to operate out of the Army Air Corps grass airfield of Netheravon. The airfield had a couple of grass runways on some very undulating ground but also had an area known as North Field where helicopters could practice their manoeuvres. I flew all the usual required exercises including a simulated hydraulics failure. I then moved on to fly some autorotative approaches gearing up to practice an engine-off landing. The gusty wind was not making life easy. I mulled over whether I should fly an engine-off landing or not. These were the worse conditions I’d flown the Scout in. So I practiced another couple of autos first to ensure I had perfected the entry point and the required profile. I flew another 1,000 foot circuit, lined up into wind, advising ATC of my intentions and then closed the throttle as I lowered the collective lever smartly. Immediately the engine-out warning horn kicked off. Thankfully this only lasted a few seconds but it was good to get it over and done with before I had to concentrate on my landing. More wind meant more lift and potentially a lower run on speed so I was feeling relatively confident as I passed 200 feet or so. I was trying to nail 60 KIAS airspeed but the gusty wind was making this difficult and after one gust the rotor rpm had risen towards the upper limit so I had been forced to raise the collective slightly to ‘contain’ the Nr. This was unusual in a Scout and with hindsight was a warning sign. As normal, around 80 feet I commenced a gentle flare. Initially all went well as the rate of descent and airspeed both reduced as advertised. But then … without further warning I simply fell out of the sky. Almost certainly the gusty wind which had been blowing very strongly had, milliseconds later, decided to hardly blow at all. I suddenly lost my vital lift. I attempted to level the aircraft by pushing the cyclic forward and, as the blades of grass rushed up to meet me, I pulled the collective up to its top stop.

Bang!

I hit the, unusually dry ground, much harder than I had hoped. I bounced. Not much, but just a little. I have spoken to scores of proper army Scout pilots since and they all swear – ‘you can’t bounce a Scout.’

Well I did. The aircraft landed again and trundled just a few yards more before coming to a halt. The main rotor blades had by now slowed considerably and were flapping and sailing in the breeze. I pulled the HP cock to turn off the fuel to the motor and completed a normal shut down as I advised ATC I had a problem and was likely to be stuck there for a while.

Seconds later a face, I really hadn’t expected or wanted to see, hove into view. My fellow helicopter colleague, Tim, had been appointed as the airfield manager of Netheravon. As I clambered out he climbed off his indecently large motor bike as we inspected my aircraft together. It didn’t take an engineering expert to spot the damage.

‘Oh, you didn’t want to go and do that!’ says Tim in a voice that made me want to punch his lights out. But he was right, I didn’t. It appeared that, as my mini bounce occurred, one of the rotor blades had flexed down a good deal further than normal and had struck my tail rotor drive shaft with such force so as to shear it through. So although my pedals were applying pitch correctly – my tail rotor was no longer turning. There was no connection between the tail rotor and the main gearbox anymore.

‘Bugger!’ I had crashed a perfectly serviceable ETPS helicopter.

I called my boss … ‘Dad, I’ve crashed the car!’

………………………………………………………………………………

Test Pilot by Chris Taylor is available to order here.