Author Guest Post: Vyvyen Brendon

Children at Sea: Lives Shaped by the Waves

by Vyvyen Brendon

On the Road in Fact and Fiction

1 A fictional journey

A month or so after publication of Children at Sea I started to re-read David Copperfield (published in 1849-50 but set in the 1820s) with the local branch of the Dickens Fellowship. One of our discussions focused on Chapter XIII in which the ten-year-old orphaned hero walks from London to Dover in search of his long-lost aunt.

Fred Barnard’s title-page for the 1872 edition of Copperfield

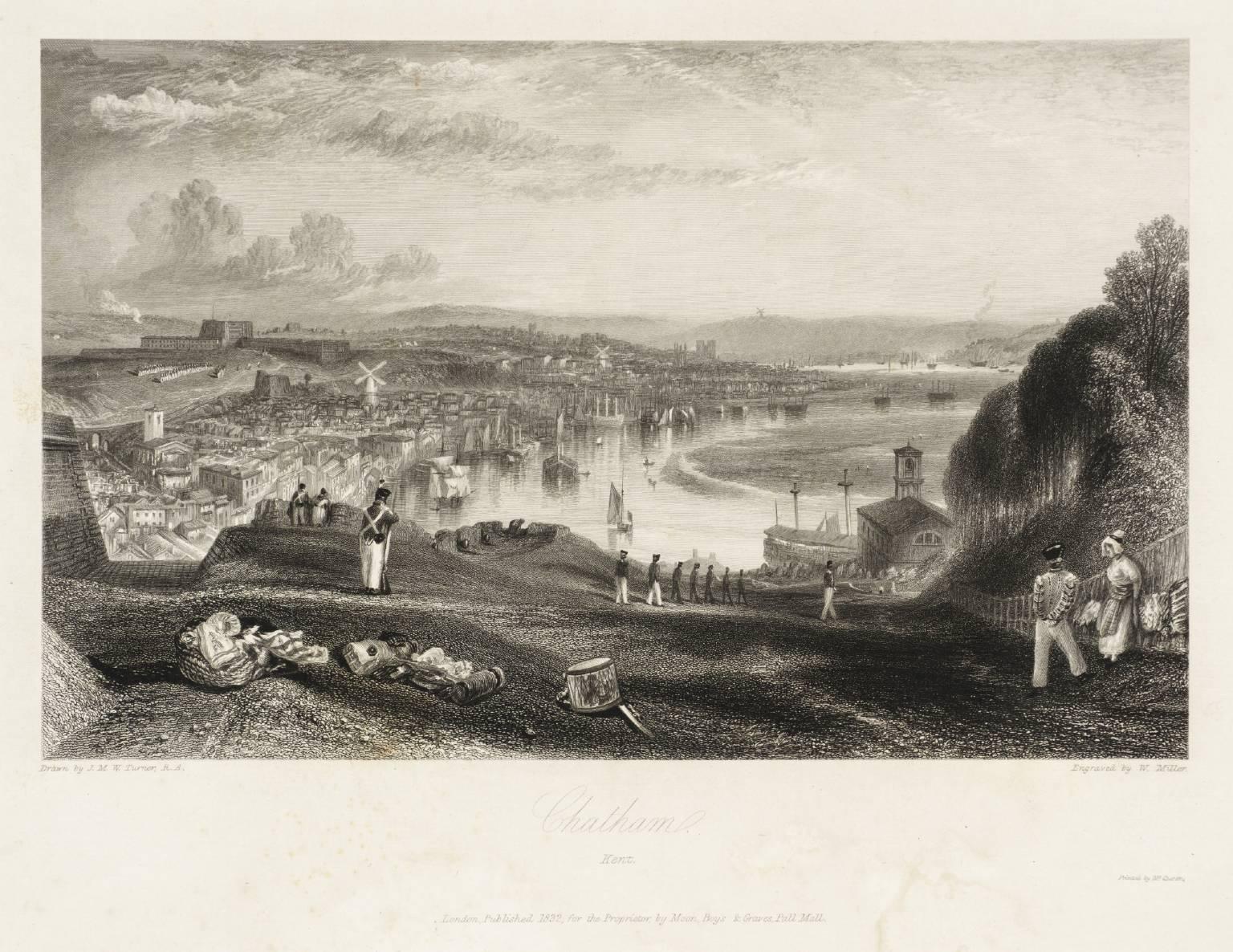

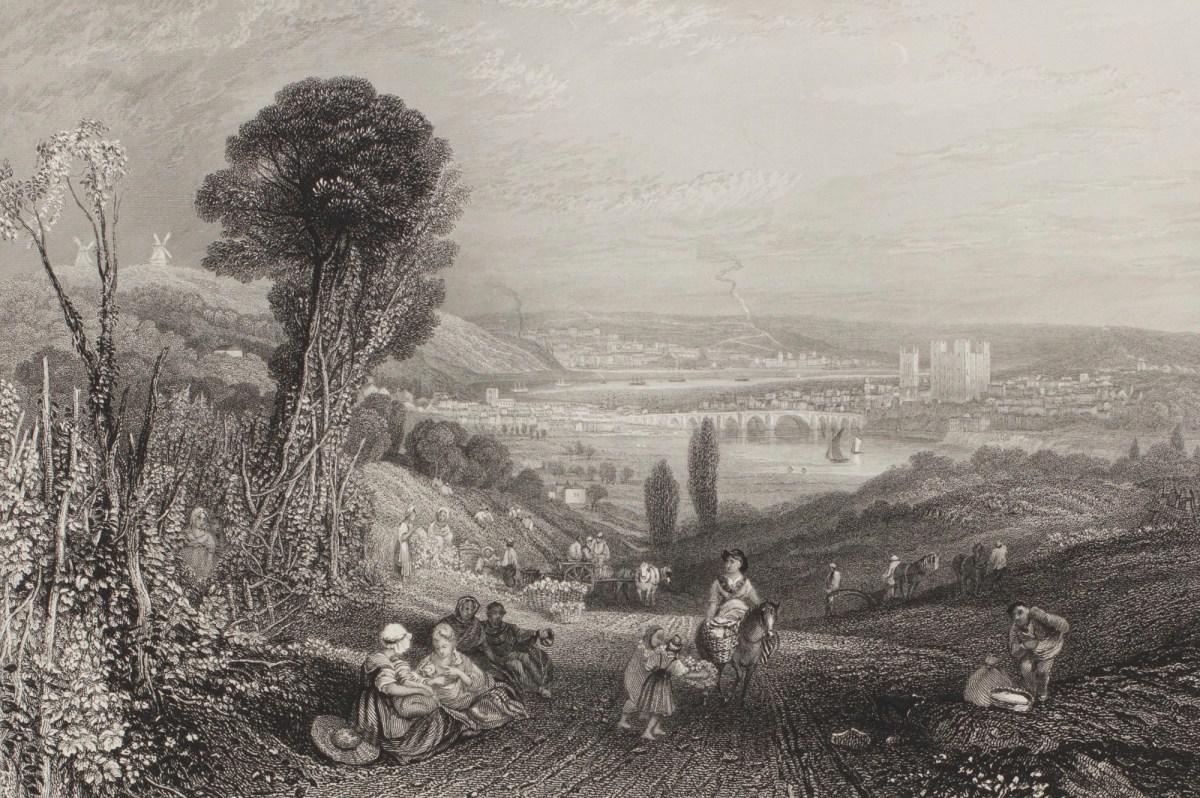

Weak, hesitant and ‘new to that kind of toil’, David spends five days on the journey, sleeping for two nights under haystacks, one night in a hop field and another beside a cannon on ‘a sort of grass-grown battery overhanging a lane, where a sentry was walking to and fro’ and where he woke in the morning to ‘the beating of drums and marching of troops’. Dickens’s description of this resting-place above Chatham was based on an area he knew very well and it exactly matches a depiction of the scene by J. M. W. Turner, who as a youth of eighteen embarked on a sketching tour along the same notoriously dangerous route, sensibly taking a companion with him.

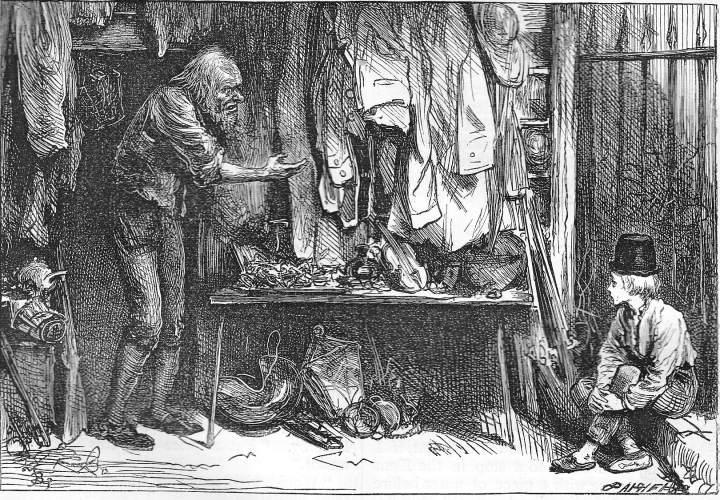

In the course of his lone journey David encounters some rather nasty characters. Clothes-dealers cheat him in Greenwich and Chatham, the first of them portrayed as ‘a man of revengeful disposition’ and the second as ‘a drunken madman’. Later a terrifying tinker robs David of his neckerchief, ‘ferocious-looking ruffians’ stone him and when he asks directions in Dover from ‘jocose and disrespectful’ boatmen they make a mockery of him. At one point he has a fleeting vision of ‘cheerful companionship’ among some early hop-pickers but this soon eludes him. (Dickens himself felt only horror and pity for the ‘miserable lean wretches’ who slept in his Kentish garden on their way to the hop-fields.)

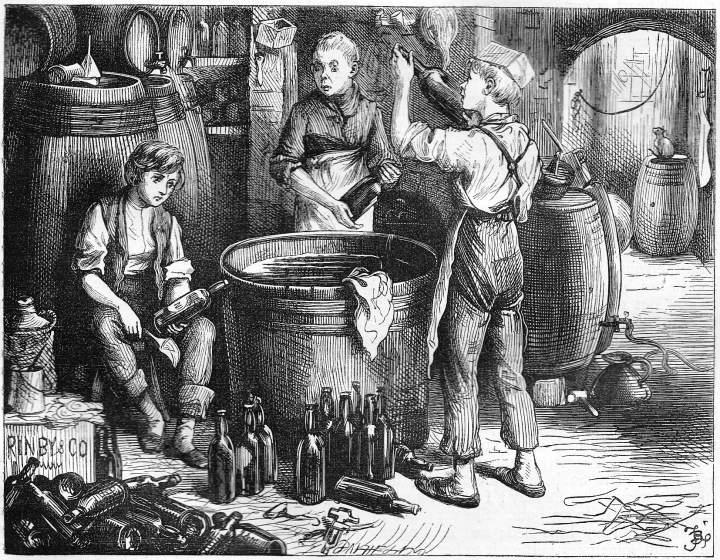

Fred Barnard’s 1872 illustration of the demented old second-hand dealer in Chatham

Only the memory of his mother ‘in her youth and beauty’ gives David the courage to carry on: ‘it always went before me and I followed.’ On the last lap he meets with some kindness when a good-natured fly-driver points him on his way and gives him a penny with which to buy a loaf of bread. Even so, it’s a thoroughly miserable, frightened and bedraggled boy who arrives at Betsy Trotwood’s house.

Dickens’s account of this journey provoked strong and varying reactions among the reading group. Some members thought the writer was preoccupied with the ‘an unbridgeable gap’ between the genteel David and the ‘terrible people’ he encounters and that Dickens lacked sympathy for such unfortunate wayfarers and petty tradesmen. Others found it a convincing account of a young boy’s search for security in a precarious and threatening world as well as an authentic picture of the landless poor on the move across the English countryside. I reckoned that the best way to judge the chapter was to place it in its historical context and I was strongly reminded of a similar journey made by George King, one of the real-life ‘children at sea’ who feature in my book.

2 An orphan and a foundling

On the face of it, the two boys’ backgrounds were very different. Although born fatherless, David had a comfortable and secure early childhood in Suffolk before the remarriage and subsequent death of his mother. George’s lone mother, on the other hand, was destitute and had to consign him in 1787 to the London Foundling Hospital, whence he was sent to spend his first five years with a wet nurse in Hertfordshire.

The subsequent experiences of the two boys were not so dissimilar. Neither received more than a few years’ education – though George’s lessons from the Hospital’s conscientious schoolmaster were more thorough and humane than those meted out to David at Mr Creakle’s brutal boarding school. Neither boy knew much of the world before being sent to work at an early age, twelve-year-old George as an apprentice confectioner and David as a ‘little labouring hind’ at the wine warehouse owned by his vindictive stepfather.

Both boys deserted their employment. Unable to get on with his ‘common’ workmates and ‘thrown upon some new shift for a lodging’, David set out to find the only relation he had in the world. George was also something of a misfit among his fellow apprentices and usually spent his free Sundays at the Foundling Hospital, often attending its chapel to sing hymns and psalms with the boys. After about three years he got into a fight with a senior apprentice and decided to run away to sea with another former foundling rather than face prosecution for affray at the hands of the City Chamberlain. So he took to the road early one morning in 1804 with his possessions wrapped in a large handkerchief, hoping to join a ship at Chatham docks. His companion soon abandoned him and he carried on alone. George was older than Dickens’s hero, his journey took place rather earlier in the century and it was shorter. Even so, the hardship, exploitation and fears he experienced were not unlike David Copperfield’s.

3 An actual journey

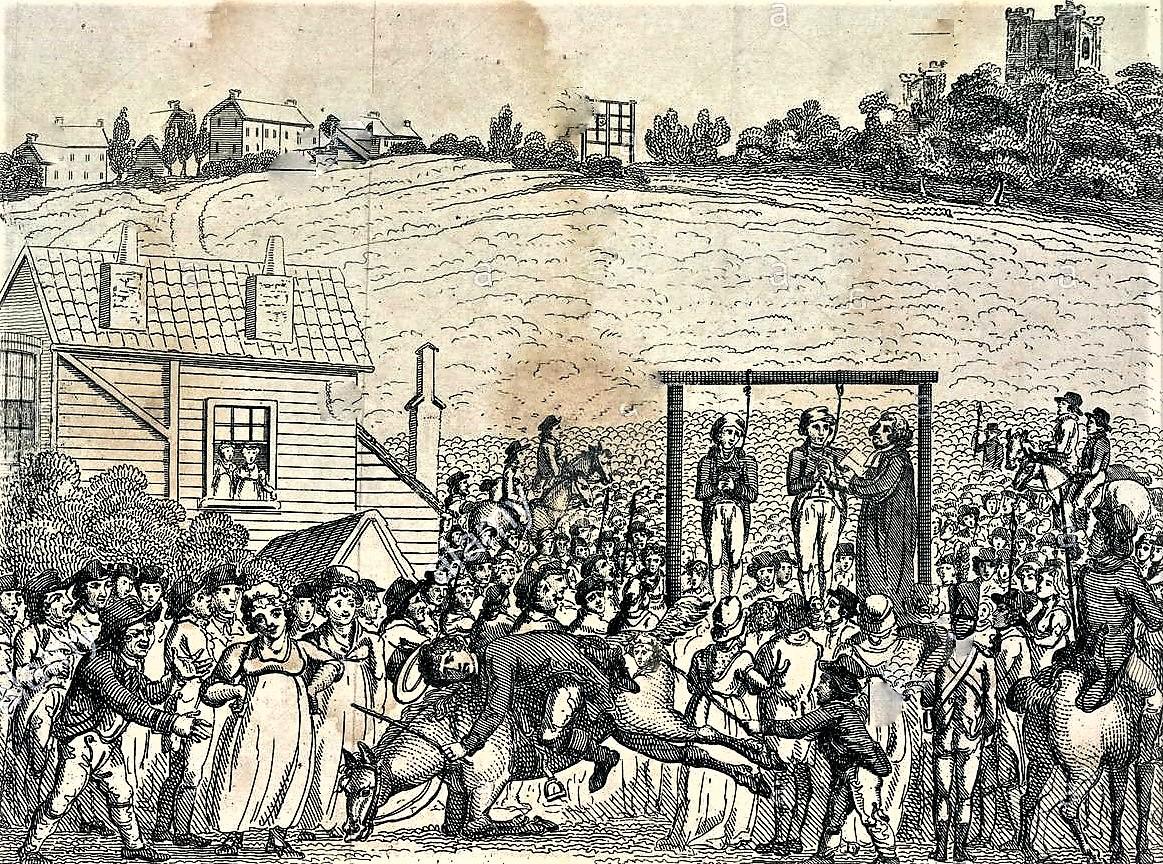

Like David, George was twice duped by clothes merchants. Near St Paul’s he sold his foundling garments to ‘a Jew singing out “any old clothes”’, who told him they were ‘only fit for boys’ and gave him too little. A slightly less extortionate trader in Seven Dials rigged him up ‘in the garb of a sailor’ with blue trousers so threadbare ‘that you might shoot peas through them’. Walking along Watling Street, the old Roman road out of London to the ports of Kent, he got drenched with rain three times in the two hours it took him to reach Shooters Hill in Greenwich. That name was enough to make him nervous, for it derived from the highwaymen who still haunted this stretch of the road – as they did Gad’s Hill, which was to be the site of Dickens’s Rochester home. The Greenwich incline was also the site of a gibbet on which such criminals were regularly hanged in the presence of crowds of spectators.

George felt safer when he chummed up with a seafaring man who recognised his nautical outfit. Along the way his new companion told him about life at sea, giving the impression that he would just have to sit down and let the winds blow him along. So cheered was the naïve George by such tales that he willingly treated the sailor to two meals of bread, cheese and generous helpings of porter before they parted company at Gravesend.

It was getting dark by this time and the boy’s spirits sank as fear, guilt and loneliness got the better of him. Worried about the consequences of leaving his apprenticeship, he became alarmed by the rustling of trees in the wind and conjured up visions of some wooden carvings which had frightened him as a small child:

I went along whistling as long as I could, sometimes running and sometimes walking, occasionally looking behind me and at this time there rushed into my head the figures I had seen above the fireplace bench at Hemel Hempstead and that caused me to perspire excessively.

Plucking up his courage George pressed on to Chatham and arrived by midnight at the Sun Tavern, where, like David in Dover, he met with some kindness. The servants shared their supper with him and the landlord didn’t press him for payment even though he stayed there for a few days in the hope that his friend would turn up. But further hazards lay in store for George. When he set out in search of his companion along the London road he was accosted by a naval press-gang, handcuffed, taken to their ‘rondy’ (rendezvous), threatened with imprisonment for having left his master and plied with grog: ‘A few hours afterwards I found myself on board of His Majesty’s Ship Polyphemus.’

Thus George entered on a life at sea which he was to describe in an autobiography written as a Greenwich Pensioner in the 1840s, the same decade in which Dickens wrote David Copperfield. George might even have read the novel in the Royal Naval Hospital’s library. Of course his ability to evoke childhood experiences, fears and imaginings comes nowhere near that of the novelist. Even so, his account indicates that ‘the Inimitable’ Dickens did not exaggerate the perils and distress a boy might experience in those days when taking to the road alone.

Here is a more benign view of Kent, showing the hop-fields which David found ‘extremely beautiful’ and where George found work before entering Greenwich Hospital.

………………………………………………..

Children at Sea is available to order from Pen and Sword Books.