Author Guest Post: Stephen Browning

DID CHARLES DICKENS INVENT CHRISTMAS?

A new book, The Real Charles Dickens, by Stephen Browning and Simon Thomas, examining many extraordinary facets of the great writer’s life and works, is due to be published this January. Here the co-authors of the new book take a look at Dickens’ influence on the Winter season and, in particular, ask the question ‘Did Dickens actually invent Christmas?’

For many Victorians, Dickens was the embodiment of the Christmas spirit. When he died of exhaustion and overwork in 1870, a London costermonger’s girl reputedly said, ‘Dickens dead? Then will Father Christmas die too?’

The origins of Christmas

So, did he invent the season? No, he didn’t but he had a profound and permanent effect on its character.

We can trace the origins of Christmas back at least 5,000 years to celebrations around the mid-winter solstice, December 21, which was very important to the people who built Stonehenge. Feasting would have included huge quantities of beef, pork, milk and cheese; probably gifts were given. This year, 2024, as every year, there will be a gathering to watch the sun rise above the stones which will occur at 8.04 am.

For the Romans, five days of feasting began on 17 December, a feature of which was the ‘reversal’ of roles whereby slaves may have been served by their masters and foot soldiers by their officers. Gifts were exchanged. The celebration was in honour of the god of agriculture, Saturn (hence the word ‘Saturnalia’).

It was in medieval times that partying began in earnest with 12 days of festivities that ended on 6 January; it was also in the 11th century that the word ‘Christmas’ began to be used. If you were wealthy enough, a pig might be slaughtered in November, then salted and smoked, in preparation for a vast indulgence of meat eating. A good meal would begin with sausages and pasties before proceeding to even more meat and fish. Any space left could be filled with tarts, sweet custards and fruit. Drinking all the while was not for the faint-hearted and non-indulgence was generally only acceptable if you had already passed out in a heap.

Tudor Christmases upped the partying and everything had a lot of sugar in it – Queen Elizabeth’s teeth went black probably as a result of the fad for sweet food. Celebrations may well have included some meat we do not eat today including badgers and blackbirds. Venison was the choice of the upper classes for which it was generally necessary to own you own deer park (it wasn’t sold in shops as it would have been far too expensive). In terms of entertainment, Shakespeare was there, of course, with Twelfth Night. Lavish presents were given on New Year’s’ night.

The Victorians refined the concept, largely as a result of Prince Albert’s influence – we have Christmas cards and gift-giving in which everyone could share; the poor could give oranges, apples or nuts if they could afford nothing else. Carols were sung – ‘Oh Come all Ye Faithful’ is one that dates from this period – and the Christmas turkey largely replaced the goose. Santa Claus was to come in the 1870’s but this was from America.

A Christmas Carol

And then, or course, just before Christmas 1843, came the publication of one of the most influential books of all time ‘A Christmas Carol’ by Charles Dickens which sold out 6 editions in a matter of days. Christmas would never be the same again.

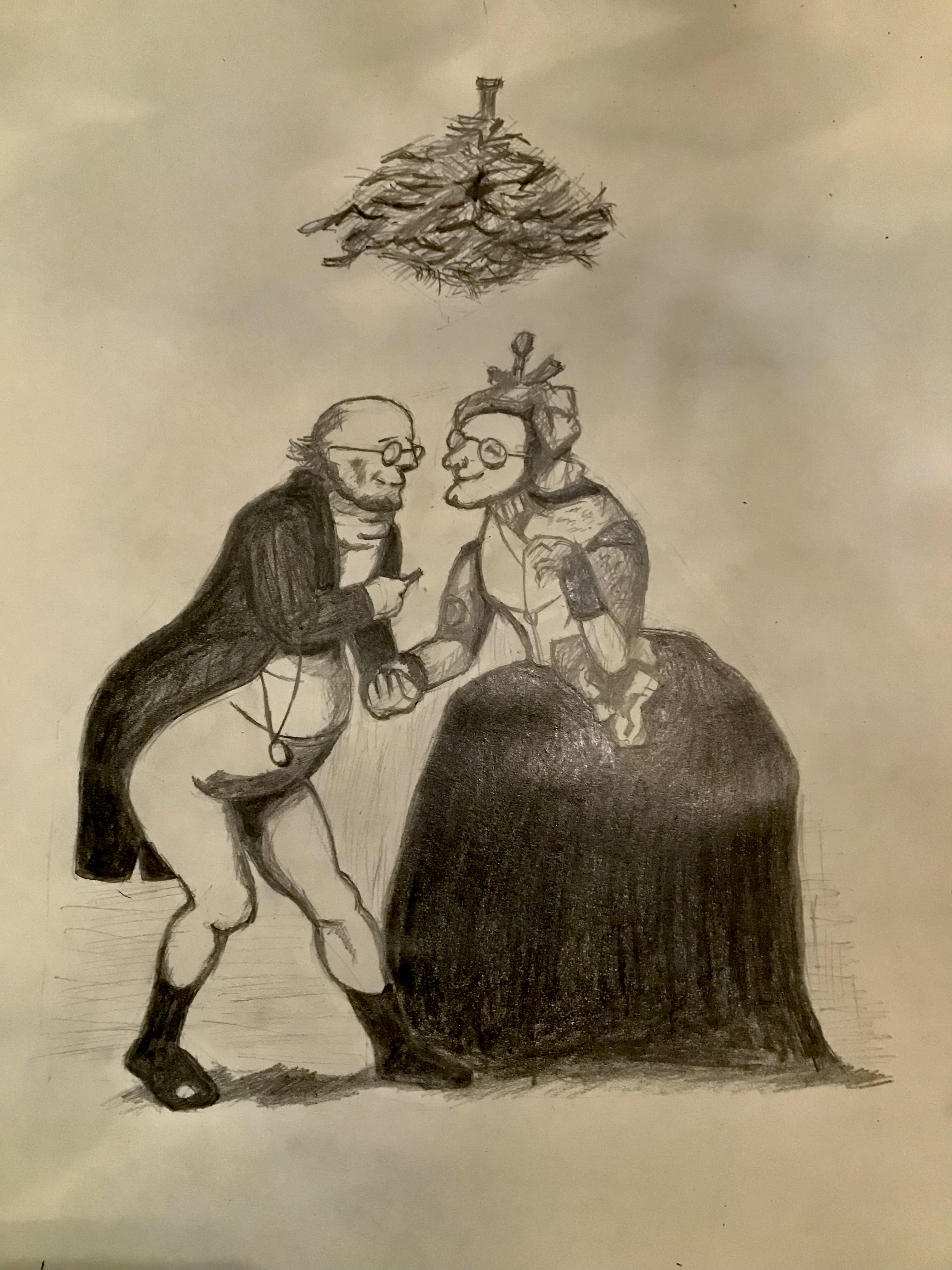

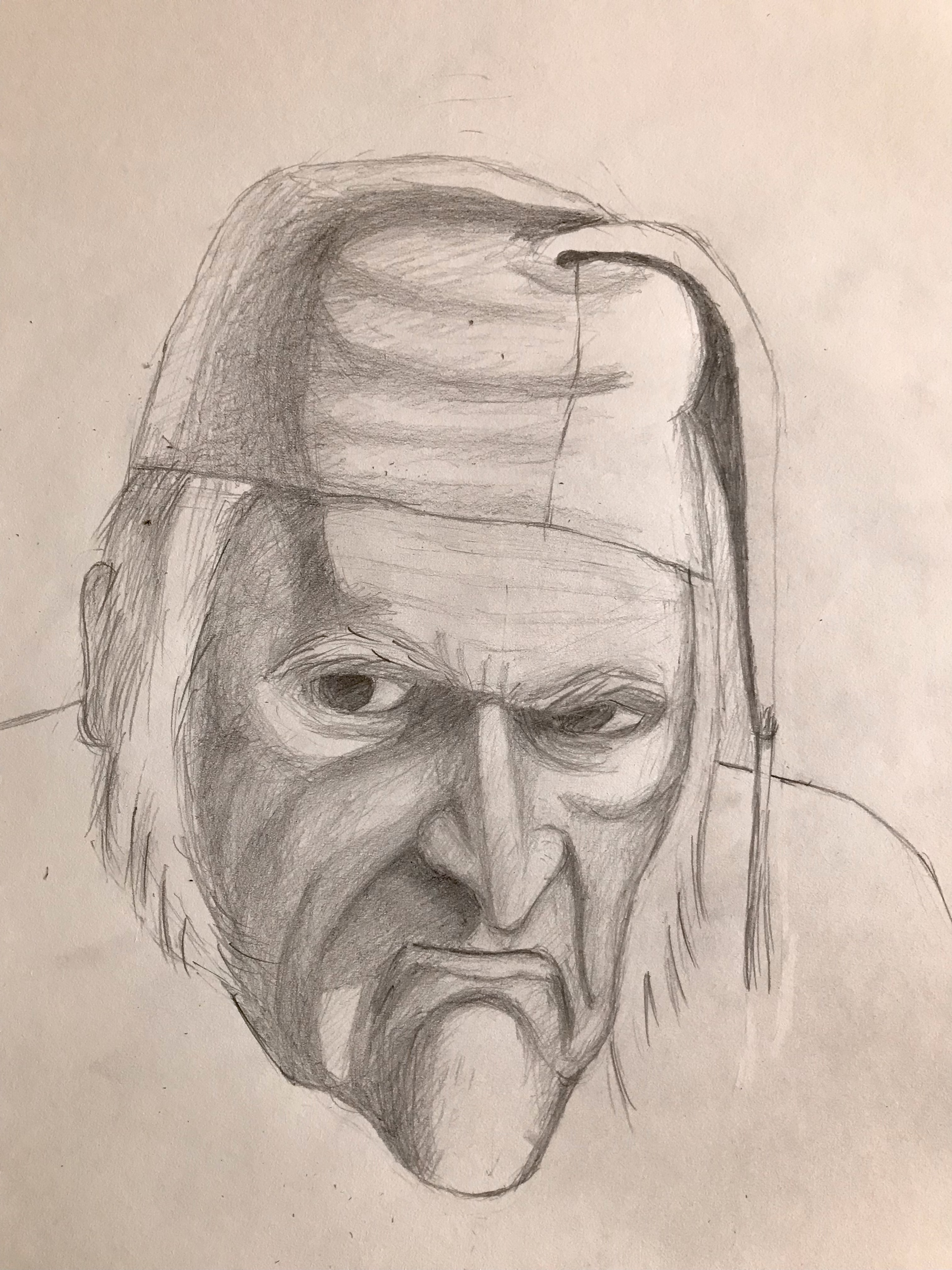

The story of the miser Scrooge, who is visited by a series of spirits – the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Future – and undergoes a conversion, has helped establish an archetype of Christmas that we still yearn for. Christmas traditions as we know them developed during the Victorian period and A Christmas Carol helped establish some of the images that still adorn Christmas cards today.

Scrooge’s “Bah, Humbug” has entered the national consciousness and the concept of salvation through kindness and compassion, which the old miser experiences over a harrowing winter’s night, gives a universally recognised definition of the Christmas spirit.

A Christmas Carol was a triumph, critically and with the public and it sold tens of thousands of copies. There was also a rush of staged versions of the story, no fewer than eight by February 1844, and its popularity as a theatrical event continues to the present day.

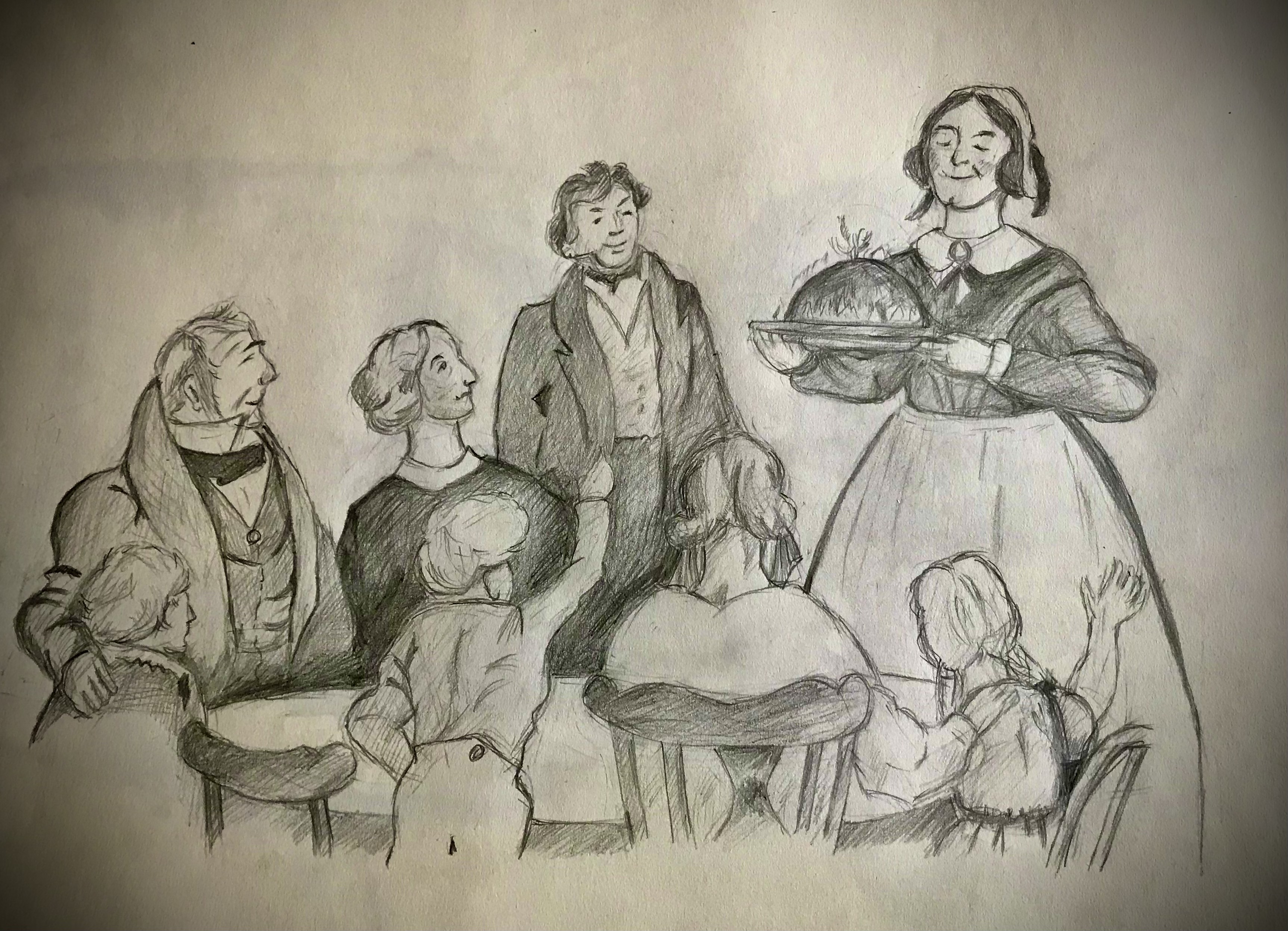

The highpoint of loving life for Dickens was the domestic fireside, preferably with some children, generously treated, and presided over by a loving woman (as opposed to a fallen woman). The Cratchit household suggested to Victorians that this idyll is there for everyone even on a very short financial shoestring.

The book was to usher in a whole new career for Dickens, as it was the first of his stories to be given public readings.

During the five years following A Christmas Carol, Dickens wrote four more Christmas books, or at least stories for the season if not about Christmas. The Chimes (1844) follows a similar formula to its predecessor but is set at New Year. Trotty Veck (so-called because he trots everywhere very fast) eats a bowl of tripe and has a weird dream in which he foresees life without him. Ghosts and spirits abound and, while it is not nearly as successful a story as A Christmas Carol, it has its charms. The next few stories, which dispense with Christmas (although the final one The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain does return to the yuletide season) are increasingly difficult and less well-known. He was never again to evoke Christmas as unforgettably as in the first book and he ended the series in 1848.

Thus, it is fair to say that, while Dickens did not invent Christmas, he undoubtedly refined it to a considerable degree, and permanently, too. This season we shall inevitably see several versions of A Christmas Carol on our TV screens as well as productions of some of the other great novels such a Great Expectations and The Mystery of Edwin Drood, in which Christmas is featured.

So Happy Christmas to all! And, as Tiny Tim says ‘God Bless Us, Every one’.

Detailed analyses of all the major novels, including A Christmas Carol, are featured in The Real Charles Dickens by Stephen Browning and Simon Thomas published by Pen and Sword in January 2025.