Author Guest Post: Simon Forty

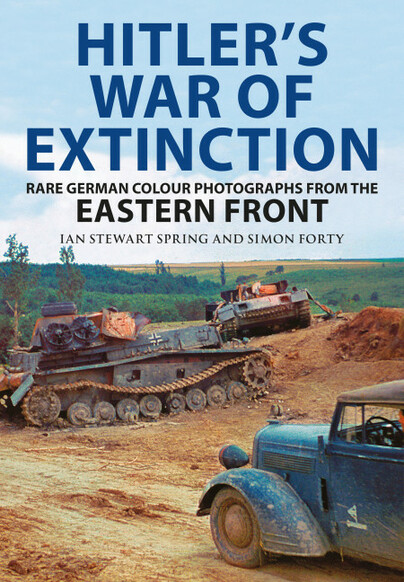

Hitler’s War of Extinction

Hitler made a momentous decision in 1941 that contributed signally to his and the Third Reich’s downfall: the commitment to the assault on his ally the Soviet Union. It was predicated on a swift Blitzkrieg victory just like those the Wehrmacht had fashioned in all its undertakings till then save for the reduction of Britain. His men – for the most part – believed in the struggle against their Communist neighbour. Indeed, for the most part they would become willing executioners of Soviets, Slavs, Jews and the other Untermenschen that stood in their path, in order to clear the way for the colonists who would follow them. Indeed, in this war of extinction while the extinction was happening to the opposition, most Germans were very happy with developments. By late 1941 everything was going swimmingly: in the east, the Ostheer was heading towards Moscow; in Africa, Rommel had pushed the British back; in the Atlantic, the British had suffered heavy losses.

December 1941 saw the first real blemishes appear in the German success story. Winter came in the east and with it a Soviet counterattack that pushed German forces back in their first major defeat. In Africa, British Operation Crusader saw the siege of Tobruk lifted and Rommel’s Afrikakorps forced to retreat leaving garrisons at Bardia, Sollum and Halfaya surrounded. In the Atlantic, the battle for Convoy HG 76 was the first Allied convoy victory with five U-boats sunk at the cost of one destroyer.

Unternehmen Taifun – Operation Typhoon, the German attack towards Moscow that had started in October – had made good progress but was slowed by the heroic defence of the Vyazma Pocket and then got bogged down in the autumn rasputitsa. The delays saw a month of German inactivity while, around Moscow, frantic work raised physical defences and reserves were brought to the front.

On 15 November 1941 a freeze began, terrain and roads once again became passable, and the attack could restart. For the German Army – overextended, battered by the heavy fighting, half its motor vehicles useless, a significant proportion of its Luftwaffe out of service and lacking decent winter clothing and equipment – it proved, however, to be one attack too many.

The Soviet defenders had suffered huge defeats during the invasion, massive losses of personnel and weapons, and initially Operation Typhoon pushed them back towards the capital but the Germans were finally held, thanks in part to the awful winter – said to be the worst Europe experienced since records began – and by the unshakeable resolve of the Soviet defenders. By early December the German attack had stalled less than 20 miles from the Kremlin in face of fierce resistance.

On 8 December 1941, Hitler accepted the position and put out Directive 39, ordering his men to stand fast: ‘Severe winter weather has come surprisingly early in the east. This has caused problems with resupply and forces us immediately to abandon all major offensive operations and go over to the defensive.’ They did so without adequate winter equipment: even the winter uniforms that were ready for use, languishing in Poland, couldn’t be brought forward because there were insufficient working locomotives, railway lines and engine drivers. The Germans had expected the Soviet Union to succumb to Unternehmen Barbarossa well before winter. Now, punch-drunk, they tottered in face of a Soviet counteroffensive that their intelligence hadn’t foreseen, spearheaded by well-equipped troops from the east. The counterattack led to the Wehrmacht’s first major defeat.

Hitler’s War of Extinction looks closely at the battlefield in wintertime:

The depth of the Russian winter came as a surprise to the Germans. It shouldn’t have done: there was plenty of information on the Arkhangelsk campaign of 20 or so years earlier. The trouble was that the Wehrmacht had believed their own propaganda that the war would be over before the snows arrived. Because of the extreme cold, ‘the mechanisms of rifles and machine guns, and even the breechblocks of artillery, became absolutely rigid. The recoil liquid in artillery pieces also froze stiff, and tempered steel parts cracked. Strikers and striker springs broke like glass. … [in] an encounter near Tikhvin when the temperature was -35°C (-31°F) only one of the five German tanks could fire.’

Fixed positions were key to defence in the winter months. In 1941–42, they were essential as defending in the open simply led to frostbite and cold injuries. With no shortage of timber or manpower, Soviet defensive positions were carefully constructed, covered over and offered warmth and protection to the defenders. When the ground was frozen, the Germans quickly learnt that grenades or explosives could help. This stoutly constructed bunker shows timber probably topped off with spoil from digging, with natural snow and sheeting to break up the gun slit. Visible inside is a PM1910/30 Maxim MG with armoured shield and crew.

In 1941/42, short on cold-weather gear, the Germans were forced to find shelter to survive—and that meant villages. They just couldn’t maintain lines out in the open without suffering huge numbers of cold-weather injuries. Control, therefore, of these vital points became the focus of fighting—and if retreat was necessary, the villages were torched so the enemy couldn’t use them. Sander noted on 9 December 1941: ‘Yesterday we were morally defeated, just like Napoleon’s victorious troops were. We were forced to retreat. We, the former Panzer men, had been sent … to cover our retreat and to torch villages! Yes, we have turned into proper murderous arsonists.’

In the freezing conditions the Germans had continuous problems with their artillery and heavy weapons, and motor vehicles, including the tanks. Starting when frozen was particularly difficult. They tried tow-starting but this damaged motors and differentials and wasn’t easy for heavy armour. In the end, keeping the engines heated with a fire underneath the vehicle or simply letting them run for hours was the only way to survive.

Don’t try this at home! Tanks don’t enjoy extreme temperatures and Panzer-Abteilung 211’s Hotchkiss tanks were no exception. Over 500 of the French light tanks fell into German hands in 1940 and they were employed as PzKpfw 35H 734(f) or 38H 735(f). Many methods were employed by armoured units to cope with the cold, including using fires under the engine to defreeze. Pz-Abt 211 was one of two units that fought in Finland. Unusually, until 1944 it was equipped completely with Beutepanzer: ex-French Army Somua S-35s and, as here, Hotchkiss H-39s (PzKpfw 38Hs).

In the first winter of 1941/42, Panzer divisions became ‘Panje divisions’ because they became so dependent on their horses. The panje horse was a small, scruffy and hardy pony used to working in the harsh conditions of the Russian winter. They couldn’t pull the weight of the draft horses, so consequently their sleds/carts were smaller but much more manoeuvrable. They needed less fodder and would survive with minimal shelter. The horse-drawn sleighs were life savers for the Germans—winter transport for supplies and for getting the wounded evacuated from the front. The horses in this photograph are too big and sturdy to be panjies—they are probably German horses. The winter of 1941–42 was too cold for many of the larger European horses, which did not survive to the spring.

Hitler’s War of Extinction brings realism to this conflict, showing the colours of war and of the landscape that it was fought in. It shows off nearly 300 original and rare colour photographs from the Eastern Front of World War II. Each one provides an evocation of what the Nazi period was like in Germany and the East during the period. They show what it was like to fight all over the Eastern Front –what went on behind the front lines as well as the fighting at the front, discussing a range of subjects – transport, logistics, partisan warfare – as well as providing portraits of the German and Red Army soldiers and their equipment. Vividly portrayed, carefully captioned, Hitler’s War of Extinction provides a different dimension for those interested in this area of the war. It will fascinate modeller or historian alike.

Order your copy here.