Author Guest Post: Shona Parker

The life of Victorian Labourers in England

Thomas Hobbes wrote in Leviathan in 1651 that man’s life was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.” 200 years later, this could still be said of the life of the Victorian labourer in England.

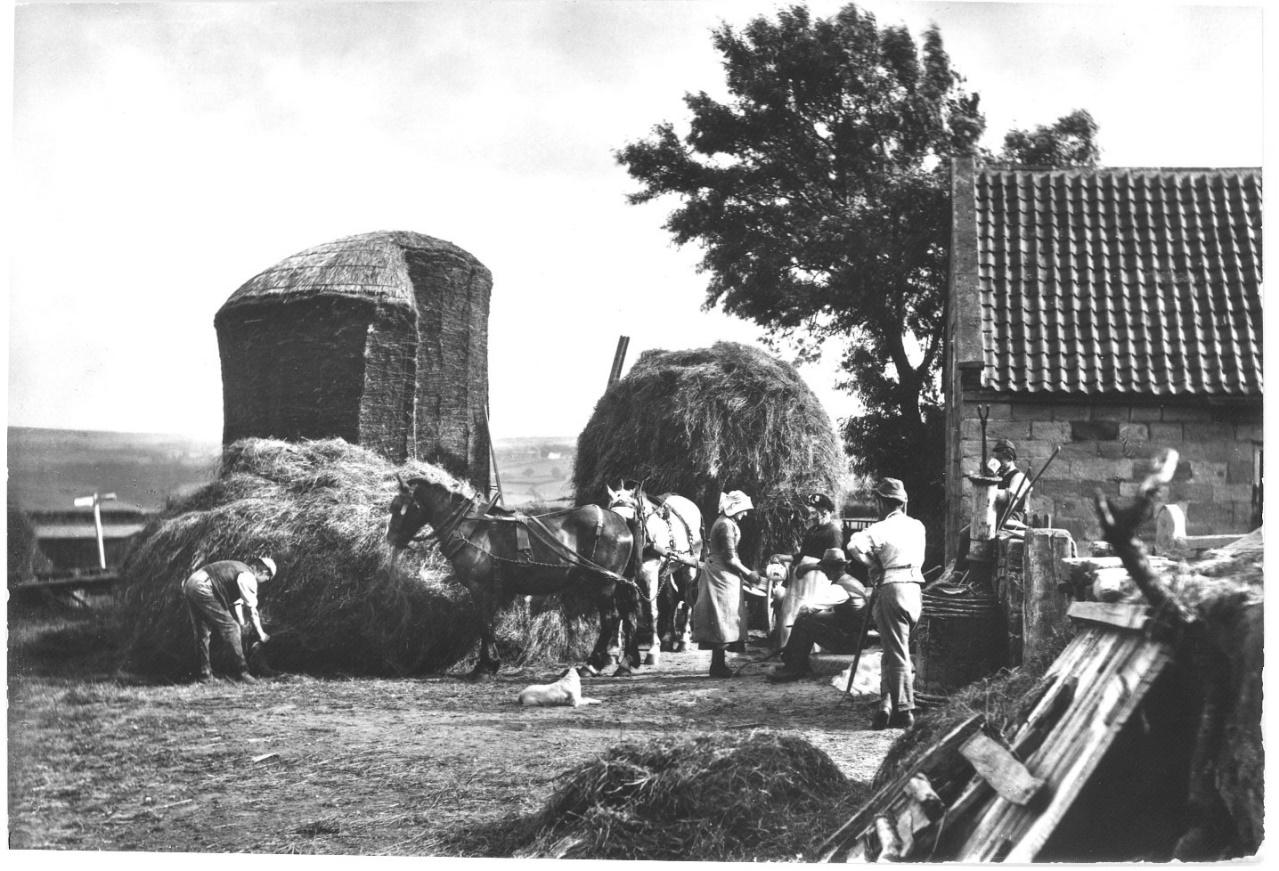

Throughout the Victorian era, the need for human labourers remained high, despite the introduction of new machinery for many jobs. Immortalised in Henry Mayhew’s ‘London Labour and London Poor’, Victorian labourers were unskilled and uneducated working class folk who had only their physical strength with which to earn a precarious living. These labourers worked incredibly long hours in often dire conditions to build the infrastructure needed in every expanding town and city throughout Victorian Great Britain, feeding the country and her empire at the same time.

The actual labouring work itself involved digging, shifting, lifting and carrying, not to mention the walk to work and back, for which labourers received a day’s pay if they completed a day’s work. Whether in the town or countryside, work started at 6.30am with a stop for breakfast around 8.00 and then working on until lunchtime when an hour would be taken for lunch and rest. Work then continued until 6.30pm with a tea break around 4pm if lucky. Once home in the evening, the evening meal would commence and then the labourer would have an hour or two to do odd jobs, rest or visit the ale house.

Despite minimal pay and poor living conditions, many labourers didn’t mind the work they did. They preferred working outside and the fluctuation and variety of work available. Also, labouring involved working as part of a community: recommending each other when extra work became available, minding each other’s children, celebrating births and supporting each other through illness and accident, of which there was much.

Thomas Hardy describes the cycle of labouring work in Tess of the D’Urbervilles:

“These annual migrations from farm to farm were on the increase here. When Tess’s mother was a child the majority of the field-folk about Marlott had remained all their lives on one farm, which had been the home also of their fathers and grandfathers; but latterly the desire for yearly removal had risen to a high pitch. With the younger families it was a pleasant excitement which might possibly be an advantage.”

Some men were fortunate to be hired as a labourer on a permanent basis. This could be in a mine or quarry, in a bricks works, as a dock worker, building houses, on civil engineering projects, the railways or more commonly, as an agricultural worker. But most men were hired on a yearly basis or increasingly, on a seasonal basis. In 1846, it is estimated that 1.5 million male and female labourers worked in English agriculture. The south of England remained the biggest employer of labourers as southern farmers were slower to adopt machinery than their northern counterparts despite growing arable crops such as wheat and barley.

Urban areas provided a wider variety of labouring jobs such as road and pipe laying, tunnel building, brick making and laying, coal porterage, house painting and ditch digging. The women were able to undertake child minding, laundry work, street selling, rubbish collecting and so forth.

Living conditions

Town labourers generally lived in cramped and unsanitary houses on crowded streets in the heart of the urban area and close to their work, or even in a room in a shared larger house. Unmarried labourers hired small rooms in lodging houses, buying their food from street sellers if the landlady didn’t provide meals as part of the rent, and washing under a cold water pump in the back yard. Married rural labourers lived in tiny cottages made up of two rooms which varied in quality. Whilst many lived in wattle and daub or mud and stud places, others, especially by the mid-century, lived in small brick cottages with two floors, adequate drainage, separate bedrooms, a shed for coal and wood, a pantry to store and prepare food and a copper or range for boiling water and cooking. Tiled and slate roofs began to replace thatch. These cottages were usually rent free as they came with the job. On one hand, this was great as it meant the family was housed properly but on the other hand, if the labourer lost his job, he lost his home too, even if he had savings with which to pay the rent. The widow and family of a deceased rural labourer also lost their claim to the cottage and would be asked to move on, regardless of whether they had somewhere to go or not, and so many ended up in the workhouse.

How did labourers improve their lot?

Labourers were classed as “deserving poor” under the New Poor Law Act of 1834 because they worked in an extremely physical job which often left them injured or plain exhausted and open to disease. They were able to claim charitable help or poor relief from the parish without resorting to the workhouse, but a labourer’s minimum wage was the amount used as a guide for any parish relief and so the poor, sick labourer and his family certainly did not become any better off by receiving some handouts.

It was very difficult for any labourer to become skilled enough to earn a better wage. They generally married at a young age and started a family soon afterwards, ensuring a life of want and need. General labourers who married before 1861 had on average 8 children. Moving a whole family like this to a bigger village or a town to take up new work was often out of the question due to a lack of savings to invest in such a move. It often took a local philanthropist such as a clergyman to sponsor a labourer and his family to do so. This lack of mobility later on in the century led to a surplus of agricultural labourers for the work required and so many moved away before marriage to towns and cities to find better labouring opportunities or different jobs altogether.

By the 1890s, married labourers had on average only 5 children. An increase in knowledge of and the acceptance of family planning enabled Victorian families to reduce the number of children they had, if they wanted to. Also, school became compulsory from 1870, and many families could not afford to keep children who weren’t working. At long last, it became socially acceptable to have less children and labourers and their families benefited from this.

It was becoming recognised by politicians that education improved people’s lives economically and the self-taught person was held up as an example of a hardworking and aspirational character. Labourers were expected to aspire to this ideal too, but their days were long, and the work was exhausting. They had very little time for or interest in politics or other national events, culture or education and so few managed to access the ever increasing opportunities to visit lectures, parks and museums. They were stoic and accepting with limited expectations; resigned to their fate with the religious belief that “God giveth and God taketh away.”

However, local schooling helped the children of labourers expand their repertoire of skills so they didn’t just follow their parents into labouring, they could try for other working class jobs instead including semi-skilled or skilled labour in factories, manufacturing and desk jobs.

But what would keep labourers in the countryside?

Agricultural labourers were far fitter and healthier than urban labourers and these were the men needed to bolster the army during times of war. The recruiting figures showed that increasing amounts of army volunteers from cities were undernourished, shorter than average, diseased or physically defective in some way or another, with their rural counterparts faring better. The government wanted to encourage rural labourers to stay in the countryside and work the land in the cleaner air and recognised that better pay and working conditions were needed. But instead, it was thought that a piece of land per dwelling would help as land is a tie: it requires constant care. The Smallholdings Act 1892 allowed farm workers to be offered small amounts of land to purchase, on which they could grow their own crops and keep their own small animals to eat or sell as they desired. This caught on in the south of England, whereas in the North, rural workers already enjoyed superior pay packets and there was less land to be parcelled up in this way.

Owning a small holding was quite a big undertaking, as the owner needed a good business sense with the ability to plan ahead through the seasons. They also needed a small amount of capital to start with to invest in seeds, tools, materials and chickens, and to keep to one side for in times of need. Access to credit would have been even better, but this was non-existent to a labourer.

Eventually, many farmers ended up using the pieces of land where they could whilst rural labourers continued to leave the countryside to labour in one of the many factories, earning better money inside the dry and warm where their work was unaffected by seasonal weather and their length of day was regulated by parliament.

Resources:

Minghay, G.E Rural Life in Victorian England (Alan Sutton Publishing Ltd 1990)

Horn, P. Labouring Life in the Victorian Countryside (Gill & McMillan Ltd, Dublin, 1976)

Mayhew, H. London Labour and the London Poor (Wordsworth Editions Ltd, Hertfordshire, 2008)

Oxford University Course Investigating the Victorians by Simon Wenham. Accessed between 6th May 2024 and 12th July 2024

www.victorianweb.org/victorian/history/work/burnett6.html

www.victorianlondon.org/etexts/hardy/tess-0051

Shona Parker’s website.

Find Shona Parker on Instagram.

Find Shona Parker on X.

Find Shona Parker on Facebook.

Order your copy here.