Author Guest Post: Robert L Evans

Air Commodore Sir Frank Whittle

On a beautiful day in October 1986 a Cathay Pacific Boeing 747 was just beginning its final descent into Hong Kong’s Kai Tak airport. This was always a rather unnerving ending to any flight, as it required heading directly towards the spectacular skyline full of high-rise towers, before making a last-minute sharp turn towards the runway. At the controls was Captain Ian Whittle, a very experienced senior pilot who had made the landing many times. This was a rather special day, however, as sitting just behind him in the jump seat was his father, Sir Frank Whittle, himself a highly accomplished pilot and flight instructor in his youth. Captain Whittle realised that his father had not made this landing before, and might therefore be somewhat anxious at the seemingly unorthodox approach. He turned around to provide reassurance to his 79-year-old father, but soon realised that he was completely at ease, and was in fact carefully scanning the vast array of instruments in the front of the cockpit. Sir Frank was, of course, the celebrated inventor of the jet engine, and as ever was most concerned with the technical performance of the aircraft and particularly the powerful Rolls-Royce RB211 turbofan engines. As the aircraft touched down Captain Whittle was thrilled to hear his father say, ‘I couldn’t have done it better myself,’ and later remarked that for him this was an occasion of great pride.1

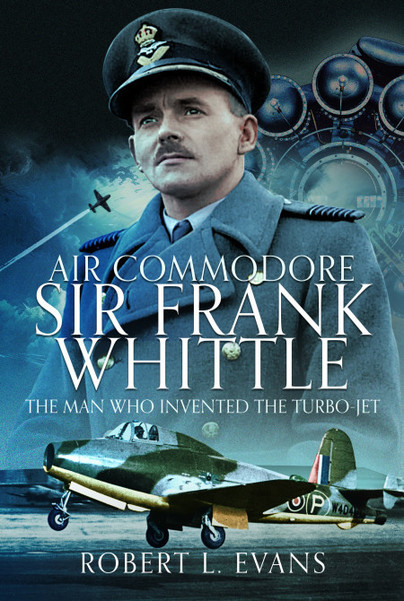

The invention of the turbojet engine, and the determined effort to design, develop and demonstrate that such a novel new engine would replace piston engines in the air, was one of the most important technical achievements of the twentieth century. That one man accomplished this working with a small but dedicated team of engineers and craftsman in the middle of a war, and in the face of many doubters, was a truly monumental achievement. The jet engine envisaged by Frank Whittle, a young Royal Air Force cadet, truly changed aviation forever, and has had the effect of shrinking the world we live in. We think nothing today of flying between continents in a few hours, when just two or three generations ago this would have been a major expedition. In short, the jet engine, developed with great tenacity by Whittle, has made the world a village, and has introduced worldwide travel to ordinary people everywhere. This accomplishment was all the more remarkable given Whittle’s humble background as the son of a highly skilled but largely uneducated mechanic and machinist. He had the necessary intellect, vision, drive and dedication, however, to make his dream of flying higher and faster a reality. This incredible accomplishment was not without considerable personal cost though, as Whittle had to face the realities of war, as well as various personal and commercial interests that nearly turned his dream into a nightmare.

My own interest in this remarkable story began on 25 May 1973, when I was near the end of my post-graduate studies in the turbomachinery laboratory of the engineering department at Cambridge University. This laboratory, dedicated to research on advanced jet engine components, had just been built and Sir Frank Whittle was invited to officially open the new facility, later to be named the Whittle Laboratory. Along with most of the other postgraduate engineering students, I hadn’t really known much about the early history of my subject, and so wasn’t expecting too much from the opening ceremonies. When Sir Frank arrived, with little fanfare, he was certainly polite when meeting faculty and students, bur appeared to be rather diffident and reserved. This all changed, however, as he stood up without notes, and for about twenty minutes recalled some of his early struggles to design and build a completely new type of aero engine and demonstrate its ability to replace the conventional piston engines then universally used. He described, in a clear and steady voice, how the very first jet engine to run started, and then quickly accelerated to destruction even after he had closed the main fuel valve. Although he had remained at his station at the controls next to the engine, many others in attendance were not quite as calm and ran for their lives down the factory floor!

……………………………………………

Order your copy here.