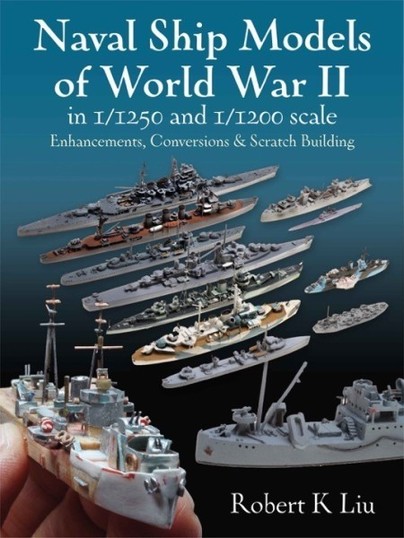

Author Guest Post: Robert K Liu

A TALE OF TWO MAYAS

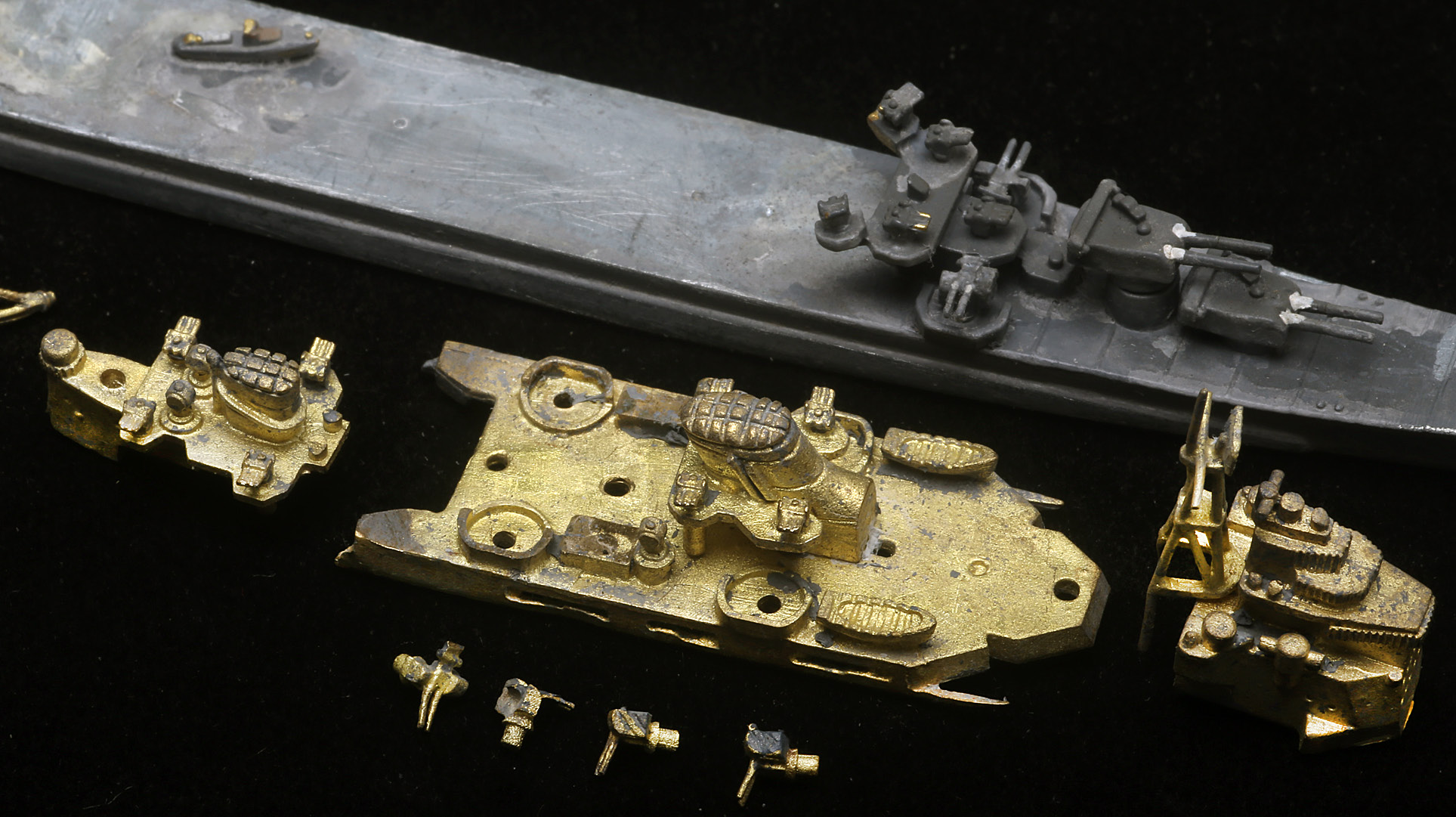

Since the start of the pandemic ‘lockdown’ and the subsequent passing of my wife and partner in publishing, I have had next to nothing to do with miniature naval ship models except for the final editing of my book ‘Naval Ship Models of World War II’ for Seaforth. Recently, however, I saw a damaged Konishi Maya for sale on the web site 1250ships. While I had aircraft and a submarine from this Japanese firm, I had never owned any of their larger models. I was eager to examine one of them closely, as they were made from lost-wax cast brass, a technique not used by any other ship model producer.

In this process, wax models, usually cast in moulds from a metal or master from a hard enough material to withstand mould-making, are invested in a plaster-like substance, which is then put in a kiln to melt out the wax, leaving a cavity shaped exactly like the now melted-away model. Molten metal is then poured into the hardened mould; after the metal hardens, the mould is broken off, to reveal the metal casting, which is then cleaned up. Thus, in this process, the mould is sacrificed with each casting, requiring a new mould to be made each time. This is unlike silicone moulds, which can be re-used for between ten and two hundred times before the mould is too damaged for further use.

Damaged models, like damaged jewelry, attract me like a magnet. Although my training and first career was as a biomedical scientist, in which I still maintain an active interest, for the past forty-five years I have been a researcher and writer about personal adornment. In this field, damaged objects almost always reveal more than intact examples. Thus I was eager to examine this Konishi Maya and compare it to a similar Neptun Maya, which would have been cast in a silicone mould with a soft alloy of tin, antimony and bismuth, called Wismut by German producers.

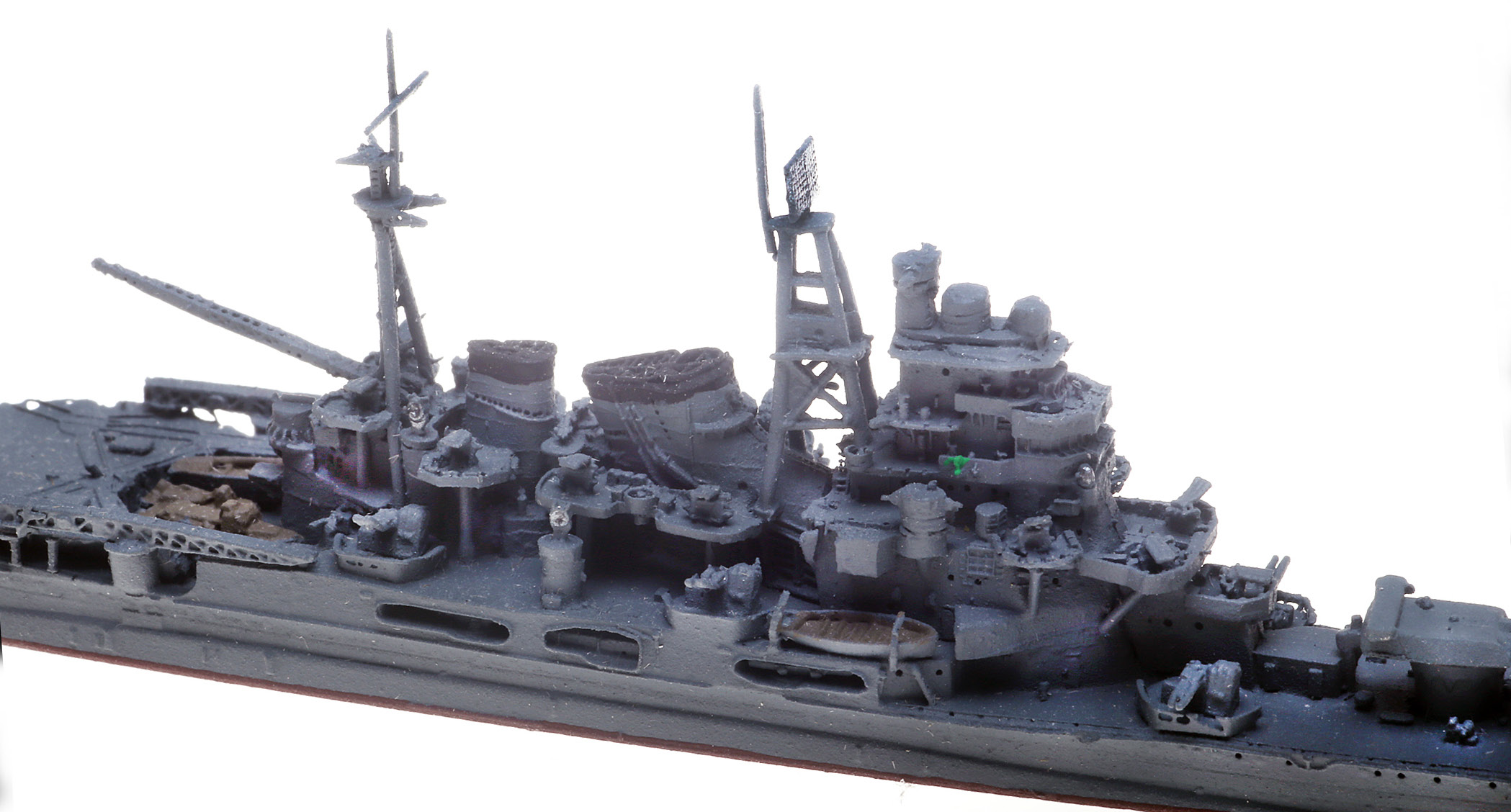

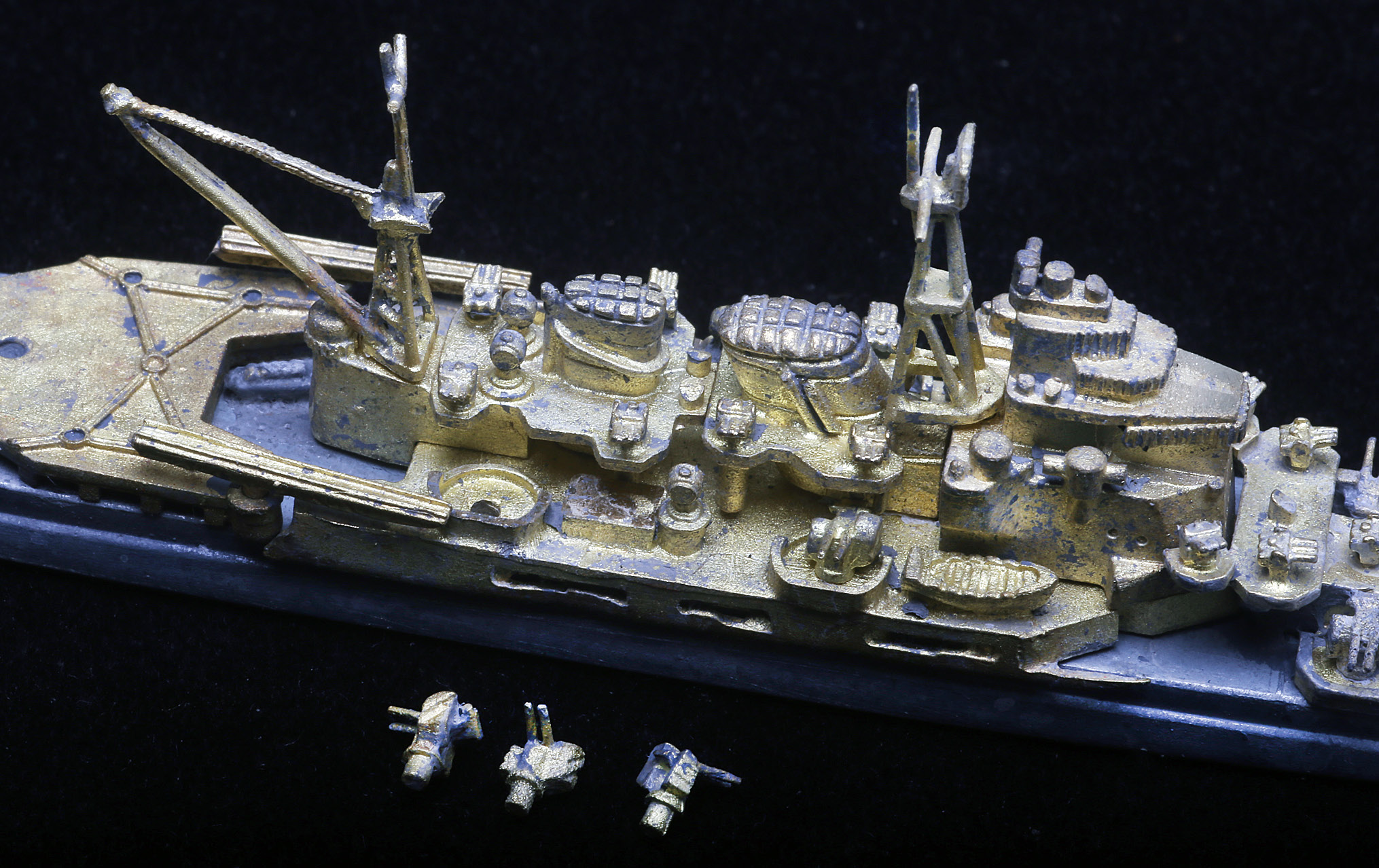

Before working on the damaged Japanese-made model, the superstructure of which had come unglued, I carefully took comparison photos using a stock Neptun Maya, also configured for 1944. Whenever I do a restoration or enhancement of a model, I always document the initial condition. The plan was to clean up and repair minor damage to the Neptun Maya, and slightly enhance the model by adding correct yards and a ‘Jake’ floatplane. The soft alloy 12.7cm gun barrels are very susceptible to damage, as they extend beyond the hull, so handling often bends or breaks them. A number had to be replaced with copper wire, a difficult gluing task. This was not a problem with the Konishi model, as the cast brass barrels are much stronger.

For the Konishi model, since it was now almost bare metal, I did much more detailing: adding correct mast features, yards, RDF loop, Type 13 radar, a radar room in the foremast, replacing a missing ship’s boat, a ‘Jake’ floatplane and adding individual single 25mm, using PaperLab’s new 3D-printed resin guns. Seven such weapons were shown in the Maya 1944 drawing on page 56 in Steve Wiper’s 2008 book on Takao class cruisers, although Japanese plans show up to twenty-one single 25mm guns. The actual Maya had twenty-eight single 25mm AA. The over-scale cable for the crane was also removed, and not replaced.

The most difficult parts of this project were the replacement of broken 12.7cm barrels, the fabrication and gluing of the Type 13 radar, and the installation of single 25mm 3D-printed resin guns. Resin is very fragile and breaks easily, and the guns’ small sizes and very light weight results in their easily slipping off tweezers and getting lost. I broke or damaged four out of the set of ten resin guns, so I had to adapt one single 25mm from a triple 25mm mount, also made by PaperLab. Thus this improvised 25mm gun consisted of three parts, made of resin, stretched plastic sprue and forged copper to form the round base of the mount. As shown in the close-up photo, this scratch-built 25mm did not quite match the other guns. In order for the yards and air search radar to be at right angles to the hull, considerable adjustment was necessary for the legs of the foremast.

This modelling project demonstrates my primary goals: to learn about how miniature naval ship models are made and to portray them as accurately as possible, although this is not achievable, as in this instance. Obtaining enough resin single 25mm guns and installing all twenty-eight of them would have probably driven me beyond my patience level.

Why I continue to be intensely interested in naval ship models of WWII, and why I have written a book on the same topic, has to do with how much my life was affected by this conflict. I was born in 1938, in Rome, Italy, when my father was the Chinese ambassador to Mussolini’s government. Prior to that he served as Chinese minister to Germany and Austria, when Hitler was in power. The Sino-Japanese war had already started, and when Japan joined the Axis, the friendly relations between China and Germany/Italy ended. We returned to China on the Italian liner Conte Verde, my father leaving for the wartime capital of Chungking, while we became stranded in Japanese-occupied Shanghai. While there, the city was bombed, most likely by B25s of the Fifth Airforce. In late 1944, my mother and five children left on a three-month journey to Chungking, traveling by train, wheelbarrow, mule cart, on foot at night to cross enemy lines, pulled on wooden sleds across the frozen Yellow River, and finally by open US International cargo trucks. After VJ day, most of the family flew to Nanking in a C47 troop carrier, landing at an airport full of surrendered Japanese warplanes. My late, oldest brother Johnny flew back in the tail gunner’s position of a Chinese B25. In 1946, we came to the United States on the USS Marine Lynx, newly disarmed, for the older children to attend school, but the Communist takeover prevented our return.

All photographs by Robert K. Liu, using macro lens and studio strobe lighting.

Preorder a copy here.