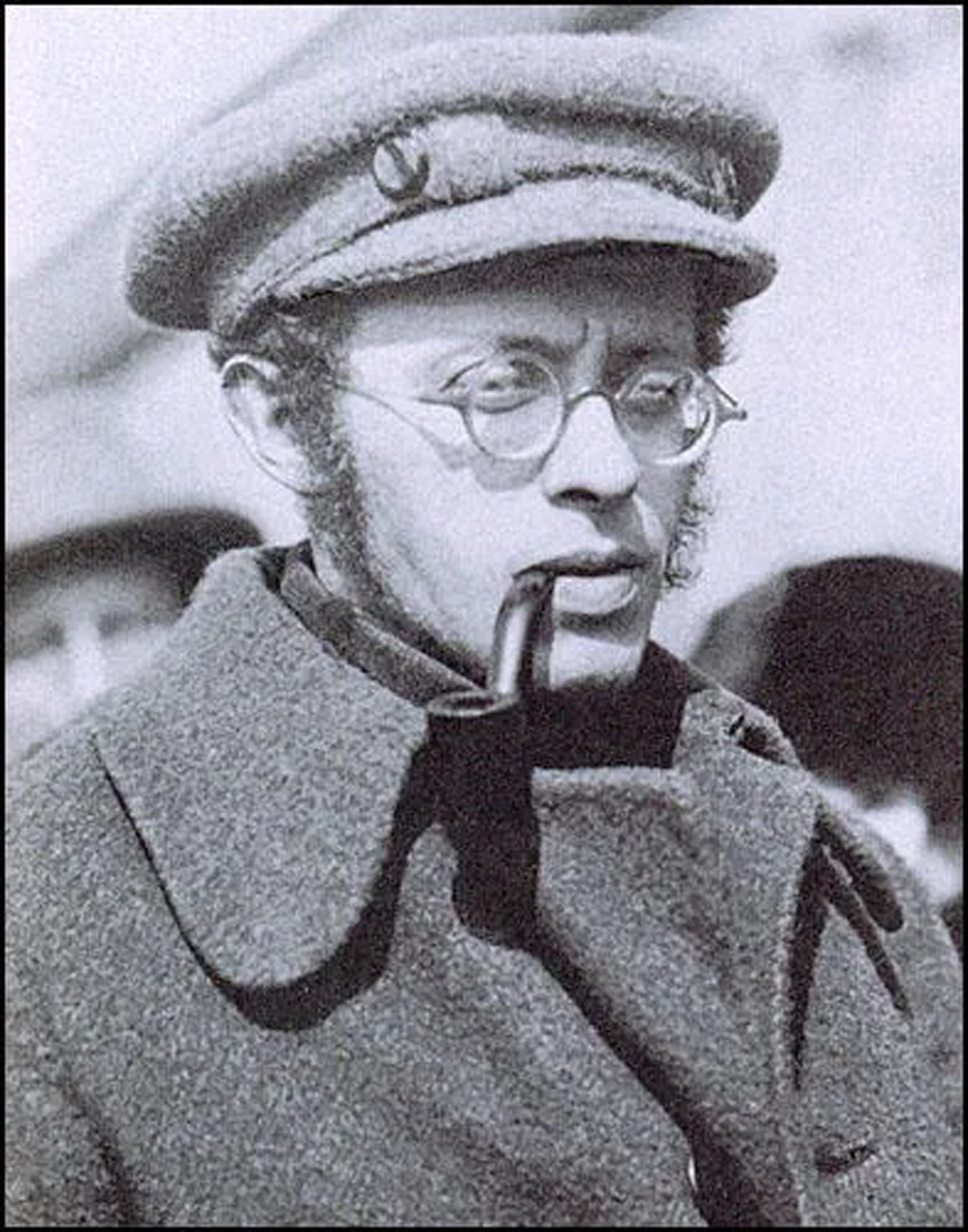

Author Guest Post: Norman Ridley

Karol Sobelsohn (Karl Radek)

Karol Sobelsohn was, in the words of his biographer, Warren Lerner, the Last Internationalist and the epitome of a Marxist internationalist. Born into an Austrian Galician Jewish family in Lwów in 1885, the young Sobelsohn was brought up speaking German rather than Yiddish but by thirteen he was also fluent in Polish which took him to the brink, but not beyond, of Catholicism. Moving to Cracow, he met Feliks Dzierżyński and found Marxism instead. Clearly very bright, at a very early age he had gained a reputation for volubility, irresponsibility and a sharp tongue that was to get him into no end of trouble.

In his early twenties he moved to Germany and met Rosa Luxemburg and through her came into contact with many of the leading European Social Democrats before being exiled to Switzerland where he met Vladimir Lenin. He was with Lenin on his famous ‘closed train’ journey to Moscow when he relieved the tedium of the journey by opening the train window at stations along the route and heckling the German soldiers. He actually left the train in Poland and went to Sweden while Lenin went on to start the Bolshevik Revolution. It was only in 1918 that, now calling himself Karl Radek, first set foot on Russian soil. Loping across Red Square, carrying a load of newspapers, two huge pistols strapped around his waist with Feodor Chaliapin, singing Cossack songs as they move from one Moscow cafe to another, Radek was clearly not going to allow himself to be turned into a bureaucrat.

He was a member of the Russian delegation to the Brest-Litovsk peace negotiations where he was described by the German journalist Wilhelm Herzog as having a ‘lively and ever-active mind…feverishly at work. His brain [was] filled with Germanic romanticism…rich in irony and energy…[he had] an immense historical culture and a very clear knowledge of world political relations.’ Given his fiery nature, Radek was surprisingly cautious in his political ambitions for communism and became one of the main links with Reichswehr military leaders in the Weimar Republic.

Entering Germany in 1918 disguised as a Austrian POW he joined up with Luxemburg in the founding of the German Communist Party [KPD]. Motivated by a grander vision than that of the just the creation of a greater Russian state, he had precisely the qualities of talent and temperament to make him a superb spokesman for the cause but after an abortive KPD bid for power in Germany, Radek, Luxembourg and Karl Liebkbecht were hunted down with a reward of 10,000 marks being offered to anyone who gave information leading to their arrest. He was eventually arrested on 17 February while attending a meeting of the Red Soldier’s League and incarcerated under military protective custody in Berlin’s Moabit Prison. Luxemburg and Liebknecht were arrested brutally beaten and murdered by Freikorps units.

Allowed out of prison, Radek was confined to house arrest when he had meetings with the German industrialist and future German Foreign Minister, Walter Rathenau. He was by no means operating in any official capacity for the Soviets but the range and variety of other calling to talk to Radek was impressive. Two such visitors were ex-Turkish Minister Talaat Pasha and his brother Enver Pasha who were personal friends of Weimar’s military chief Hans von Seeckt. Radek dearly wanted to meet von Seeckt but the Prussian could not allow himself to be associated with him so instead he arranged for General von Reibnitz to look for common ground in a German-Russian military front against Poland and a way of forging economic ties between Russia and Germany, despite defeat in war still an industrial giant with technical expertise second only to the U.S.

On 10 January 1920, Radek met high-ranking German officials to discuss the reconstruction of Russian industry with German financial and technical assistance. To allay fears and in accordance with Trotsky’s personal stance, he told the German representatives, Deutsch and the German Foreign Minister Walter Simons, that Russia had no intention forcing Bolshevism on Germany. Radek noted that ‘German business circles…were the pillars of German-Soviet relations.’ and, with his customary cynicism, made clear his view that for purely financial reasons as much as anything else ‘nothing will happen that will permanently block our way to a common policy with Germany.’ A complete rupture with the Soviets could prove to be a very expensive mistake for German industry.

Negotiations resulted in secret military cooperation between the two countries but Radek was beginning to find life uncomfortable given his closeness to Leon Trotsky and a commitment to exporting communism which was not at all what Stalin had in mind. Yet despite his later abandonment of Trotsky and submission to Stalin, his star inexorably waned until he fell victim to the purges in 1937 which, given his nature and his history was inevitable really. He avoided the firing squad but got into a fight in the gulag to which he had been exiled with a fellow inmate called Varezhnikov and was killed. It was later claimed that he had been assassinated on the orders of the KGB.

The Road to Barbarossa is available to order here.