Author Guest Post: Norman Ridley

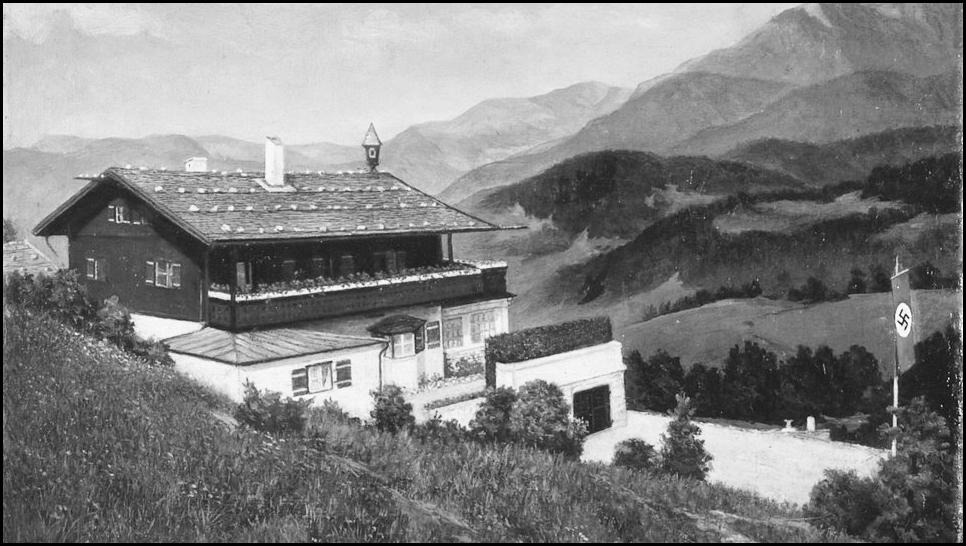

Hitler’s Berghof

The Berghof was built in 1916 as a family retreat by the businessman Otto Winter in the stunningly beautiful and dramatic Berchtesgaden region of Bavaria close to the Austrian border. He called it Haus Wachenfeld. Hitler, who was a frequent visitor to the area, first rented the house in 1928 and then bought it in 1933 using money from the sales of his book Mein Kampf. It was under the auspices of Martin Bormann, who had been appointed asset manager that refurbishment took place. He appointed Albert Speer, one of Hitler’s favourite architects to carry out the building work and another architect and interior designer Gerdy Troost came in to renovate the interior. When it was finished Hitler renamed it The Berghof (Mountain Court).

A large terrace was built which allowed for the siting of big, colourful canvas umbrellas. The dining room was panelled with very expensive cembra pine and a great hall was furnished with heavy, wooden, expensive Teutonic furniture. One room was specially arranged as a cinema where Hitler spent many hours watching Hollywood films.

A large complex of mountain homes for the other Nazi leaders such as Bormann and Hermann Göring were built nearby. This meant the compulsory purchase of nearby properties with severe penalties to anyone who refused to comply. Adjacent to the Berghof was barracks for a detachment of Liebstandarte SS Adolf Hitler who patrolled a sealed off, strictly guarded area which became a Führersperrgebiet with communications and housing infrastructure suitable for the government.

Hitler received many important guests at the Berghof including David Lloyd George on 3 March 1936 and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor on 22 October 1937 but the most famous encounter was that with British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain on 15 September 1938. Previous to this, Lord Halifax, who at the time was Lord Privy Seal and who would later become British Foreign Secretary, was invited to meet Hitler at the Berghof on 17 November 1937 and almost caused a diplomatic incident by inattention. Hitler would often dress up in the most bizarre fashion and when Halifax arrived by car at Hitler’s residence he mistook the ‘man in black trousers, silk socks and patent leather shoes’ waiting to greet him for a footman and it was only a timely interception by one of Hitler’s aides that prevented Halifax handing Hitler his hat and coat. The slight may well have been noticed by Hitler, however, who spent the whole lunchtime meeting in ‘a peevish mood’ and refused to be sociable. When Halifax went on to visit Göring’s Carinhall estate he found the Reichsmarschall would not be outshone as a fancy dresser. Upon arrival, Halifax was greeted by ‘a great schoolboy in his boots, breeches, jerkin and green hat with a large chamois tuft.’

The famous ‘appeasement’ meeting with Chamberlain had been hastily arranged more or less as a personal initiative by the British Prime Minister to defuse the Czechoslovakian crisis. Hitler agreed to meet because, after all, he had nothing to lose and it would make him appear a reasonable man but he had no intention of giving an inch of ground. A memorandum was signed which Chamberlain interpreted as ‘peace for our time’ but which Hitler later told his Foreign Minister was ‘a piece of paper of no significance whatsoever.’

To understand the powerful impression Chamberlain must have gained from this visit it is worth recounting a description of the Berchtesgaden written by the French Ambassador in Berlin, André François-Poncet, after his visit in October 1938:

From a distance, the place looks like a kind of observatory or small hermitage perched up at a height of 6,000 feet on the highest point of a ridge of rock. The approach is by a winding road about nine miles long, boldly cut out of the rock. The road comes to an end in front of a long underground passage leading into the mountain and closed by a heavy double door of bronze. At the far end of the underground passage a wide lift, panelled with sheets of copper, awaits the visitor. Through a vertical shaft of 330 feet cut right through the rock, it rises up to the level of the Chancellor’s dwelling-place. Here is reached the astonishing climax. The visitor finds himself in a strong and massive building containing a gallery with Roman pillars, an immense circular hall with windows all round and a vast open fireplace where enormous logs are burning, a table surrounded by about thirty chairs, and opening out at the sides, several sitting-rooms, pleasantly furnished with comfortable armchairs. On every side, through the bay-windows, one can look as from a plane high in the air, on to an immense panorama of mountains. At the far end of a vast amphitheatre one can make out Salzburg and the surrounding villages, dominated, as far as the eye can reach, by a horizon of mountain ranges and peaks, by meadows and forests clinging to the slopes. In the immediate vicinity of the house, which gives the impression of being suspended in space, an almost overhanging wall of bare rock rises up abruptly. The whole, bathed in the twilight of an autumn evening, is grandiose, wild, almost hallucinating.

Hitler couldn’t get Chamberlain out of his sight quick enough but was seriously dismayed to hear news of the cheering and adulatory crowds that lined the streets of Munich as Chamberlain drove back to the airport. Beside himself with anger, Hitler told Mussolini, who had been present at the meeting, that Chamberlain ‘haggled over every village and petty interest like a market-place stall keeper, far worse than the Czechs would have been! What has he got to lose in Bohemia? What’s it to do with him? He keeps talking about fishing at weekends. I never have weekends – and I hate fishing!

In the Summer of 1943, further building work took place to fortify the building and construct a bunker and tunnel complex. British and U. S. bombers struck on 25 April 1945 dropping almost 2,000 tons of bombs on the Berghof and surrounding area. The Berghof itself was badly damaged by two bombs and SS troops burned what was left before abandoning the area. The local population looted what was left and the Bavarian authorities wiped out all traces of the building in 1952 to prevent it becoming a shrine for neo-Nazis and a place of interest for tourists.

………………………………………………………………………………

Order Reading Hitler’s Mind here.