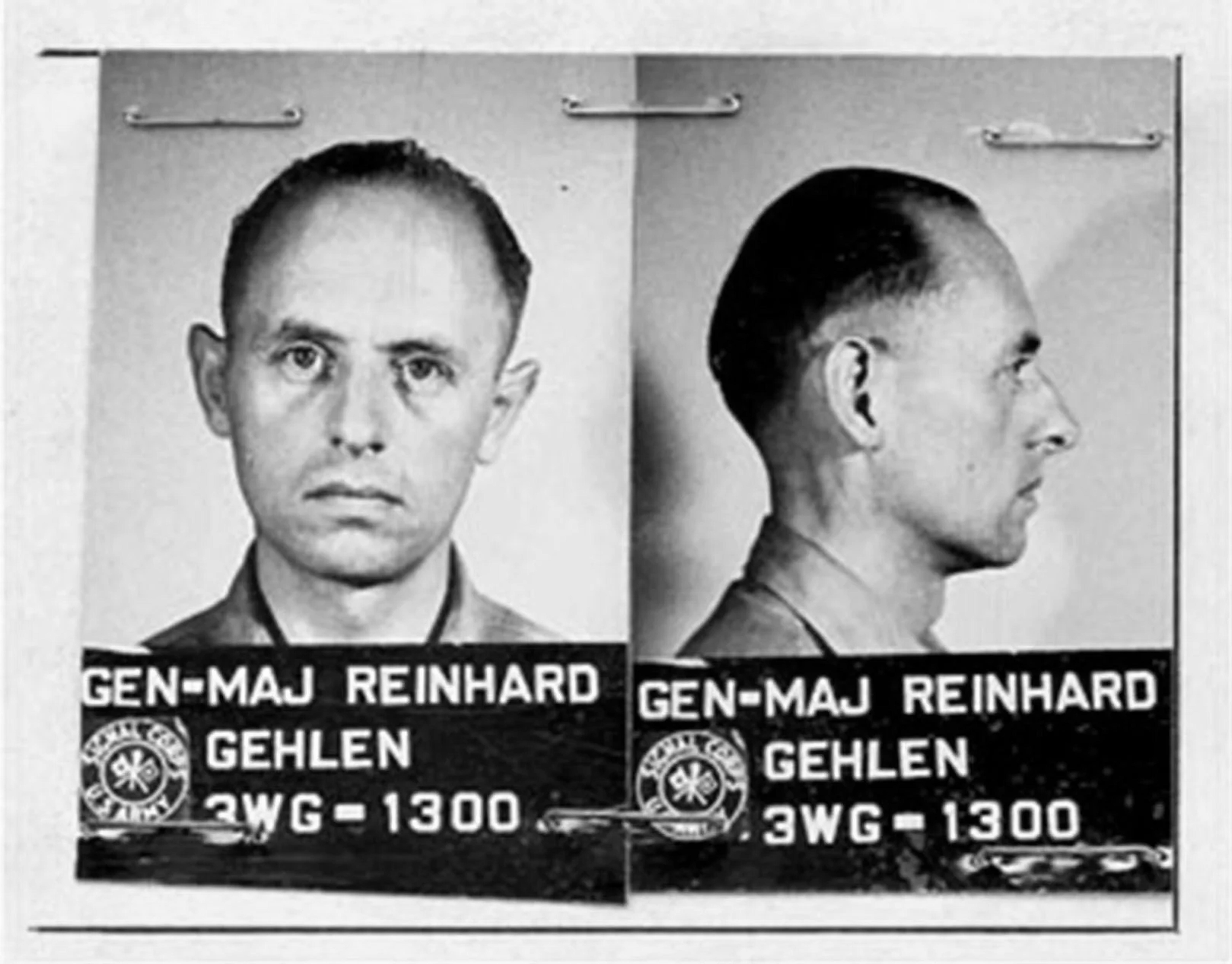

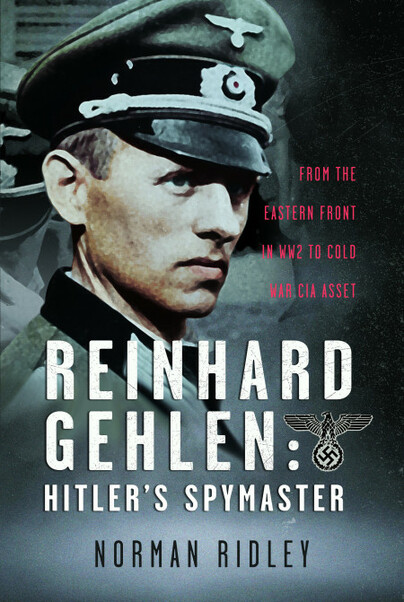

Author Guest Post: Norman Ridley

REINHARD GEHLEN: HITLER’S SPYMASTER

In this blog, Norman Ridley, author of Reinhard Gehlen: Hitler’s Spymaster, explores how this senior Nazi intelligence officer set out to land himself in American custody at the end of the war in Europe.

During the Second World War, Reinhard Gehlen had faced many situations where, as head of German military intelligence on the Eastern Front, he had sat up late into the night writing his reports agonising over whether he had overlooked some crucial piece of information or drawn an unwarranted conclusion that might have unforeseen, catastrophic results. It was like that now in spring 1945, but he was no longer weighing up the fate of armies in the field. His priority at this moment, with the war playing out its final agony all around, was survival for himself, his family and his staff – and it was in the deep, narrow valley of the river Valepp that weaved its way between the high peaks of the Stolzenberg and the Kreuzbergerkopf on the German-Austrian border in the Bavarian Alps, that he considered his options.

With him were six of his officers and three female staff assistants and they were all, technically, deserters from the German armed forces. If caught by the SS they would be hard pressed to talk their way out of a peremptory firing squad. On the other hand, discovery by advance US forces would see them thrown in prisoner of war camps where it might take many months before Gehlen could negotiate his way to an interview with the people he needed to contact, and by then it might be too late.

Capture by the Red Army was something that he tried not to think about at all. He was cool, analytical, pragmatic and a strategist by inclination, and, however, he had a plan. It was a plan so fantastic that, if successful, it would have consequences way beyond any issue of immediate survival for him and ones that would underscore the political landscape of Europe for years to come.

Gehlen had spent many hours in the Bavarian Alps as a young military cadet in happier times and was therefore familiar with his surroundings. Now, with his nine companions he climbed up a steep path through deep snow to an isolated alpine cottage sitting high above the valley floor at a place the locals called ‘Misery Meadow’.

A shepherd, Rudolf Kreidl, wounded and discharged from military duty, had shown them the way. It was exactly what Gehlen was looking for as a hideout with the narrow German-held territory being inexorably squeezed by Soviet tanks rolling through the streets of Vienna, Austria, and US General George Patton’s Third Army crossing the river Rhine. Here in the heart of the Alpine Redoubt some of the remaining Wehrmacht and Nazi leadership planned to make their last stand and sue for peace, but SS units were terrorising the region bent on rooting out and executing enemies of the state. In his madness and uncontrollable fury at what he saw as Germany’s failure to live up to his demands, Adolf Hitler had ordered that his forces laid Germany to waste leaving only a scorched earth for the victors. It was a perilous environment and one made even more dangerous by the fact that Gehlen was planning treason on an unimagined scale.

Gehlen had travelled south from Zossen, near Berlin, over roads now subjected to constant air attacks and choked with the desperate and pathetic mass of refugees fleeing bombed-out cities frantically trying to keep out of the clutches of Soviet forces in the east. Their nightmare journey took them through SS roadblocks where anyone even suspected of desertion or illegal activity was taken aside and shot. Although Hitler, in one of his insane rages, had relieved him of his command on 9 April 1945, Gehlen still carried documentation of a one-star Wehrmacht general that enabled him to reach Bad Reichenhall in Upper Bavaria, just a little more than 10 miles north of the Führer’s Berchtesgaden.

Although the recent flight from Berlin had been catalysed by his dismissal, Gehlen was now playing out a scenario that had been some time in preparation. In February 1945, he had rescued his wife and four children from Liegnitz, now directly in the line of the Soviet advance, and instructed one of his staff, Major Hermann Baun, take them to a place of safety way to the south at Naumburg in Thuringia. They passed through Dresden only days before it was fire-bombed by 1,000 Allied aircraft; Baun’s wife who ran a small hotel in the city remained and was one of the 30,000 people who died there on 13 February 1945.

Baun had also taken with him two lorry loads of some fifty steel boxes containing the whole archive of Gehlen’s intelligence files. This included index files of Red Army personnel and Soviet politicians, aerial photographs of Soviet cities and industrial regions, and coded lists of German agents operating behind Soviet lines.

Events now led Gehlen to believe that Thuringia would end up in the Soviet zone of occupation, so he quickly arranged for his family and the archives to be moved again, this time to an isolated house, Gutmanning, at Cham on the Czech border. It was at this place that he held a short family reunion to celebrate his wife’s fortieth birthday on 17 April 1945.

When he left his family after a few brief days, there was no certainty that he would ever see them again, but Gehlen stuck to his plan and headed for Valepp. There he waited until the time was ripe for him to take the world’s most valuable collection of espionage files, gathered over three years of war against the Soviets, and hand them over to the Americans.

Order your copy here.